Primary Central Nervous System Vasculitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Primary central nervous system vasculitis, or primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) is a distinct inflammatory vasculitis restricted to the brain, spinal cord, and meninges, affecting both arterial and venous vessels. In contrast, secondary central nervous system (CNS) vasculitides are associated with other systemic conditions and are far more common than PACNS.

Etiology

The precise etiology of PACNS remains ill-defined but multiple infectious agents have been implicated including varicella zoster virus (VZV) and Mycoplasma among others (Table 1). The mechanism for PACNS also remains largely unknown, but it is hypothesized to be a post-infectious inflammatory response.

Table 1: Proposed triggers of PACNS[1]:

| Viral infections | Varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus, cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19 |

| Bacterial infections | Treponema pallidum, Borrelia burgdorferi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Bartonella henselae, Rickettsia spp |

| Fungal infections | Aspergillosis, mucormycosis, coccidioidomycosis, candidiasis |

| Parasitic infections | Cysticercosis |

| Connective tissue disease | Systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, dermatomyositis, mixed connective tissue disease |

| Miscellaneous | Antiphospholipid antibodies syndrome, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, neurosarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, graft-versus-host disease, bacterial endocarditis, acute bacterial meningitis, drug-induced CNS vasculitis (cocaine, amphetamine, ephedrine, phenylpropanolamine) |

Risk Factors

No specific patient related risk factors for PACNS have been proven but PACNS tends to occur in older individuals, with several studies suggesting a median age of diagnosis at around 50 years.[1][2][3][4] PACNS, however can occur at any age including children.[5] Furthermore, some older reports suggest a 2:1 male predominance, but more recent case series do not suggest a sex preference.[1][2][6]

Pathophysiology

PACNS can be divided into three main subtypes: granulomatous, lymphocytic, and necrotizing disease. All subtypes involve inflammatory infiltrate into or around cerebral arteries. T cells have been implicated in the pathology of PACNS, specifically in immunohistochemical studies of cerebral vessel biopsies that stain positive for CD4R50+ T cells.[1] Some cases of PACNS have overlap with inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy.[1][2][3][4][7] Some authors have suggested that PACNS may arise as an inflammatory response to β-amyloid deposition, an outcome that has been observed in animal models.[7][8]

Histopathological findings

The gold standard of PACNS diagnosis is transmural inflammation of the leptomeningeal or parenchymal vessels on histopathology.[1][3][9] However, multiple subtypes of PACNS have been observed. The most common is a granulomatous vasculitis, characterized by transmural, well-formed granulomas.[1][2][3][4][9] β-amyloid deposition is most commonly associated with the granulomatous subtype, seen in up to 50% of these patients in some case series.[1][3][6][8] Further subtypes in order of prevalence include lymphocytic and necrotizing PACNS. Lymphocytic PACNS is characterized by lymphocytic infiltrates and plasma cells, while necrotizing PACNS involves fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall.[1][2][3][4][6]

Diagnosis

History

The classic picture of PACNS is of focal neurological deficits with no clear secondary etiology after neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. Symptom onset in PACNS is usually insidious, in many cases occurring over several months before a diagnosis.[1][2][3][4][5] Some patients can present with rapidly progressive symptoms, which generally indicates a poorer prognosis.[1][9]

Symptoms and signs

Focal or generalized headache is the most common presenting symptom of PACNS, seen in up to 63% of patients. Cognitive dysfunction is the second most common symptom, seen in up to 54% of patients. Both headache and cognitive dysfunction in PACNS are typically progressive but the diagnosis may remain elusive in the acute setting.[1][2][3][4]

Many patients with PACNS present as a stroke like episode or a transient ischemic attack and focal neurological deficit (e.g., hemiparesis or hemisensory loss). Large vessel symptoms such as aphasia are less common.[1][2][3][4] In addition, unlike other systemic vasculitides, constitutional symptoms (e.g., fever) or elevated acute phase reactants (e.g., erythrocyte sedimentation rate) are relatively uncommon in patients with PACNS, presumably because the disease is localized to the CNS.[2][6]

In contrast, children with PACNS are more likely to present with sensorimotor signs. The most common is hemiparesis, observed in up to 80% of patients. Hemisensory deficits and fine motor deficits are the next most common symptoms, seen in 79 and 73 percent of patients, respectively. Headache and cognitive dysfunction are relatively less common compared to adult patients (56 and 37 percent, respectively).[5]

Ophthalmologic Manifestations

The neuro-ophthalmic presentations of PACNS include both afferent and efferent symptoms. Patients may complain of unilateral (e.g., amaurosis fugax) or bilateral visual loss (e.g., homonymous hemianopsia) or diplopia.[1][2][3][4][6] Inflammatory eye manifestations including uveitis or retinal vasculitis are possible, but less common in PACNS, and should prompt investigation for secondary rather than primary CNS vasculitis.[10] Papilledema is a relatively uncommon, but reported sign in PACNS.[1][2][3][4] One case of PACNS described recurrent, isolated, transient monocular vision loss and eye pain with associated optic disc edema and macular exudates in both eyes. Her visual field defect began as left inferior quadrantanopia that progressed to complete left visual field defect.[11] Another case reported the Balint syndrome (oculomotor apraxia, simultagnosia, and optic ataxia) in PACNS.[12]

Clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis of PACNS is made clinically and requires exclusion of secondary CNS vasculitis. The proposed criteria for PACNS include[1][2][3][4][6]:

1. A focal neurological deficit unexplained by other causes after thorough workup

2. Cerebral angiography suggestive for vasculitis or a positive brain biopsy

3. No evidence of other systemic vasculitis.

Laboratory tests

There is no specific biomarker for PACNS. A complete blood count with differential, basic metabolic panel, and inflammatory marker screening (e.g., erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP)) should be performed but are usually normal in PACNS. In fact, a markedly elevated ESR or CRP likely indicates a secondary systemic inflammatory process (e.g., giant cell arteritis) rather than PACNS. Further investigation for secondary CNS vasculitis (e.g., antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, serum protein electrophoresis, and other autoimmune markers) can be performed.[1][2][3][5]Other investigations may also be warranted depending on the individual clinical presentation.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis also assists in the diagnosis of PACNS. Up to 90% of confirmed patients with PACNS have abnormal, though nonspecific, CSF findings: elevated CSF protein and mildly increased leukocytes.[1] Further evaluation of CSF through culture, serology, polymerase chain reactions, and flow cytology are recommended to exclude possible infectious or malignant etiologies of abnormal CSF.[1][2][3][5]

Imaging

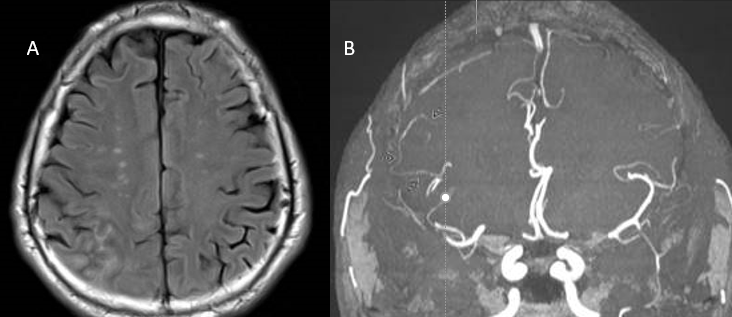

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain and spine with and without contrast is the modality of choice in initial neuroimaging of PACNS. Unfortunately, the neuroimaging findings in PACNS are nonspecific and variable, and depend on which arteries or veins are affected. The most commonly seen abnormalities are infarcts in both cortical and subcortical regions, which are frequently multiple and bilateral.[1][2][3][6] In contrast, children are more likely to have unilateral, white matter lesions.[5] Other MRI findings seen in PACNS include gadolinium-enhancing lesions, intracranial hemorrhage as a consequence of inflammation, and mass lesions that may appear to be tumors.[1][2][3]

Cerebral angiography can reveal vascular abnormalities suggestive of vasculitis and can be especially useful when biopsy is not possible. However, angiography has variable sensitivity and variations in vessel caliber and shape are not specific for vasculitis.[2][3] Many other conditions such as vasospasm, atherosclerosis, and infections can produce the same appearance on angiogram as PACNS.[1] Characteristic vasculitic patterns for PACNS include “beaded” vessels (alternating segments of stenosis and normal or dilated lumen), occlusions, and collateral circulation..[1][2][3] Both small and large vessels can be affected, departing from the convention that vasculitides only affect one type of vessel size.

Biopsy is considered the gold standard for diagnosis, and it allows exclusion of other etiologies if a representative biopsy sample is taken.[1][2][3][4][5] However, biopsy is not as sensitive as either MRI or angiography, because PACNS is characterized by segmental inflammation. Therefore, negative biopsy does not necessarily exclude disease, especially when combined with relevant history, laboratory findings, and other imaging abnormalities on MRI or angiogram. Transmural inflammation with any of the histopathological patterns described previously would constitute a biopsy-positive diagnosis of PACNS.

Differential diagnosis

As previously mentioned, PACNS is a diagnosis of exclusion. Various infections, autoimmune conditions, connective tissue diseases, and malignancy such as lymphoma can precipitate secondary CNS vasculitis (Table 2). The closest mimicker of PACNS, however, is reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS).

Table 2: Differential diagnosis of PACNS[2]:

| Noninflammatory vasculopathies | · RCVS

· Atherosclerosis · Neurofibromatosis · Fibromuscular dysplasia · Susac syndrome · Hypercoagulable state |

| Infections | · Emboli from subacute bacterial endocarditis,

· Basilar meningitis caused by TB or fungal infection, · Bacterial infections (see table 1), · Parainfection syndromes (e.g. acute disseminated encephalomyelitis [ADEM]) |

| Demyelinating syndromes | · Multiple sclerosis

· ADEM · Sarcoidosis |

| Secondary CNS vasculitis | · Large-vessel vasculitis (e.g.,, giant-cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis)

· Medium-vessel vasculitis (e.g.,, polyarteritis nodosa, Kawasaki disease) · Small-vessel vasculitis: ANCA-associated vasculitis (e.g., granulomatosis with polyangiitis (now GPA but formerly Wegener granulomatosis), eosinophilic GPA (formerly Churg-Strauss angiitis) and microscopic polyangiitis) · Immune-complex deposition (e.g., IgA vasculitis (formerly Henoch-Schönlein purpura) and cryoglobulinemia) · Rheumatic syndromes (e.g.,, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma) |

| Malignancy | · Primary CNS lymphoma

· Lymphomatoid granulomatosis · Carcinomatous meningitis · Gliomatosis cerebri |

The main criteria for PACNS is excluding secondary CNS vasculitis. In addition, RCVS can present similarly to PACNS, but its symptoms are due to vasospasm rather than inflammatory vessel destruction.[1][3][6][13] Patients are more likely young and have severe, recurrent, thunderclap headache with focal neurological signs, as opposed to the slower onset headache seen in PACNS. Furthermore, RCVS usually yields normal CSF analysis.[3] Angiography findings in RCVS can appear similar to PACNS; therefore, in a patient with angiography-positive, biopsy-negative vascular findings, careful history including time course of symptoms and exposure to vasoactive substances must be conducted. It is of particular importance to distinguish PACNS from RCVS, because RCVS and other vasoconstrictive conditions should not be treated with the immunosuppressive therapy that is indicated for PACNS.[1] In contrast, older patients with a history of lobar hemorrhage or dementia should have amyloid angiopathy on their differentials.[1][2][13]

Infection may also mimic PACNS. However, these patients are more likely to be immunosuppressed. Furthermore, distribution of involved arteries in infections generally falls into a classic pattern; for example, tuberculosis or fungal infections are more likely to have specifically basilar involvement.[2]

PACNS can also present with a mass-like lesion; one case series identified the frequency at 5.6% of PACNS patients presenting with a mass-like lesion on MRI. PACNS or brain masses can both present with normal angiography and vague history, and brain biopsy remains the gold standard for differentiating these diagnoses.[14]

Management

Medical therapy

Similar to other vasculitides, immunosuppressive therapy is the mainstay of treatment for PACNS. Treatment for PACNS should be given in conjunction with a neurologist / rheumatologist, but may include steroid therapies, and cyclophosphamide.[1][2][6] Steroid side effects should be monitored for and managed, including ophthalmic side effects such as glaucoma, cataracts, and hyperglycemia-associated vision abnormalities.[1] Depending on other factors, anticoagulation may also need to be considered, especially in children.[5]

Patients who do not respond to cyclophosphamide or steroids can be treated with second-line agents such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockers.[1][6][15] Infliximab and etanercept have shown positive responses in patients with rapidly progressive PACNS.[1][15] Less evidence exists for rituximab as a second-line therapy for PACNS, but a case report following two patients did suggest a positive role in treatment-refractory disease.[16]

Complications

Neurological deficits and cognitive dysfunction may persist depending on treatment duration, time to diagnosis, and severity of disease.[1][2][3][5][6][13] Relapse is somewhat common in patients with PACNS, and more likely in those with large vessel involvement.[13] Flares of disease may be associated with additional neurological deficits. However, patients generally respond well to more intensive therapy. Patients with PACNS have higher risk of death compared to the general population due to cerebrovascular complications such as infarction.[1][2][3][6][13]

Complications resulting from therapy should also be considered. Patients should be monitored for myelosuppression and opportunistic infections, as well as hemorrhagic cystitis if receiving cyclophosphamide.

Prognosis

The extent and size of involved vessels impacts prognosis, as large vessel disease is generally associated with poorer outcomes.[6][13] In any patient, however, early diagnosis and treatment can reduce presenting symptoms of disability and prevent further neurological sequelae.

Summary

In summary, ophthalmologists should be aware that PACNS can present with afferent (visual loss) or efferent (diplopia) ophthalmic complaints depending on the location of the vasculitic process. The main role of the ophthalmologist is excluding evidence for secondary CNS vasculitis (anterior or posterior uveitis) and performing a formal visual field (homonymous hemianopsia) if indicated. Ophthalmoscopic examination for optic disc edema (papillitis) or papilledema might also be helpful in formulating a differential diagnosis. The evaluation, management, and treatment of PACNS, however, typically requires multidisciplinary (e.g., neurology and rheumatology) efforts.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Hunder GG. Adult primary central nervous system vasculitis. Lancet. 2012;380(9843):767-777. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60069-5

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 Birnbaum J, Hellmann DB. Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(6):704–709. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2009.76

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 Salvarani C, Brown RD, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Annals of Neurology. 2007;62(5):442-451. doi:10.1002/ana.21226

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Calabrese LH, Duna GF, Lie JT. Vasculitis in the central nervous system. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1997;40(7):1189-1201. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199707)40:7<1189::aid-art2>3.0.co;2-4

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Benseler SM, Silverman E, Aviv RI, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis in children. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(4):1291-1297. doi:10.1002/art.21766

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Christianson T, et al. An update of the Mayo Clinic cohort of patients with adult primary central nervous system vasculitis: description of 163 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(21):e738. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000738

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: comparison of patients with and without cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(11):1671-1677. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken328

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Winkler DT, Bondolfi L, Herzig MC, et al. Spontaneous hemorrhagic stroke in a mouse model of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Neurosci. 2001;21(5):1619-1627. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01619.2001

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 Giannini C, Salvarani C, Hunder G, Brown RD. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(6):759-772. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-0973-9

- ↑ Rao NM, Prasad PS, Flippen CC, et al. Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System Presenting as Unilateral Optic Neuritis. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2014;34(4):380-385. doi:10.1097/wno.0000000000000147

- ↑ Rao NM, Prasad PS, Flippen CC, et al. Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System Presenting as Unilateral Optic Neuritis. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2014;34(4):380-385. doi:10.1097/wno.0000000000000147

- ↑ Jacobs DA, Liu GT, Nelson PT, Galetta SL. Primary central nervous system angiitis, amyloid angiopathy, and Alzheimer's pathology presenting with Balint's syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49(4):454-459. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.04.002

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 de Boysson H, Zuber M, Naggara O, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: description of the first fifty-two adults enrolled in the French cohort of patients with primary vasculitis of the central nervous system. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(5):1315-1326. doi:10.1002/art.38340

- ↑ Molloy ES, Singhal AB, Calabrese LH. Tumour-like mass lesion: an under-recognised presentation of primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(12):1732-1735. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.096800

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Efficacy of tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade in primary central nervous system vasculitis resistant to immunosuppressive treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(2):291-296. doi:10.1002/art.23337

- ↑ De Boysson H, Arquizan C, Guillevin L, Pagnoux C. Rituximab for primary angiitis of the central nervous system: report of 2 patients from the French COVAC cohort and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(12):2102-2103. doi:10.3899/jrheum.130529