Posterior Keratoconus

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

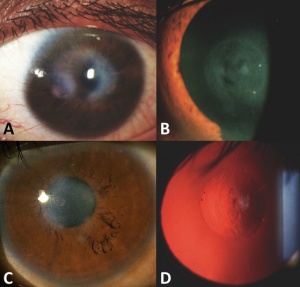

Posterior keratoconus (PKC) or keratoconus posticus is a rare, usually congenital corneal disorder where there is an increase in curvature of the posterior corneal surface and is often associated with a corneal stromal opacity.

Disease Entity

Disease

Posterior keratoconus (PKC) or keratoconus posticus is a rare, usually congenital corneal disorder where there is an increase in curvature of the posterior corneal surface. PKC exists as two subtypes[1]:

- Keratoconus posticus generalis, when the entire posterior cornea is affected.

- Keratoconus posticus circumscriptus, when the abnormality is localized.

- Subclassified as central/paracentral localization or peripheral localization.[2]

Often, PKC is associated with a corneal stromal opacity.[3]

Etiology

The etiology is unknown. The disorder is thought to be rare, although the precise prevalence is also unknown. PKC is most often congenital, unilateral, and sporadic. Some familial cases have been reported and frequently display an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance.[4] These cases often present with a variety of systemic abnormalities and syndromic features such as cleft lip/palate, webbed neck, extremity defects, and/or genitourinary abnormalities.

Risk Factors

There are no known risk factors for the congenital form of PKC as it is thought to be sporadic. For the acquired form, ocular trauma and other events resulting in disruption of the inner corneal layers have been indicated as inciting factors.

General Pathology

Histologic analyses of the thinned zone have shown various abnormalities in Descemet’s membrane, such as disorganized and widely spaced collagen with abnormal banding and a multilaminar configuration. Descemet’s membrane is generally intact, although there may be small breaks and hyaline excrescences.[3][5][6] The endothelium is also typically intact with occasional guttae. Electron microscopy has identified areas where Bowman layer is replaced by randomly arranged collagen and fibroblasts. The epithelial basement membrane may be disorganized with overlying abnormalities in the basal epithelial cells.[5][7][8]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of PKC remains unknown, although the histologic and clinical findings in these patients suggest that PKC may arise as a result of anterior segment dysgenesis and may be the mildest form of Peters’ anomaly. It is unclear whether delayed separation of the lens from surface ectoderm[9][10] or abnormal migration of mesenchyme[2][3][5][8][11] leads to the clinical manifestation of PKC.

Despite the concurrence with various systemic abnormalities, such as cleft lip/palate, webbed neck, extremity defects, and genitourinary abnormalities, no genetic locus has been identified. These systemic findings have been described in both familial and sporadic cases of PKC.[8][12] This suggests that PKC and these associated traits may be due to a defect in embryogenesis or early fetal development.[13] Histological analyses also support this finding.

In patients with a history of ocular trauma, PKC likely has a different pathophysiologic origin. Destruction of the inner corneal layers may lead to localized damage of Descemet’s membrane and the corneal endothelium. The subsequent tissue remodeling may lead to acquired PKC.[14][15]

Primary Prevention

There is currently no known method of primary prevention for PKC.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis for PKC is made by a combination of history, physical exam, and diagnostic procedures as described below.

History

Patients may present during adulthood for routine ophthalmic exam and endorse a history of decreased visual acuity since childhood.[13] In cases with grossly visible corneal opacification, patients may be referred to a pediatric ophthalmologist during childhood, facilitating the diagnosis.

Physical Examination

PKC can be associated with several ocular and systemic abnormalities so it is important that patients undergo a complete ophthalmic and systemic physical exam. A thorough list of the possible associated abnormalities has been published in the literature.[13]

Signs

Clinical Signs of PKC include:

- Area of corneal thinning with posterior excavation.

- Associated stromal opacity, which may be the most clinically obvious feature.

- Pigment on posterior corneal surface associated with the area of excavation.

- Clinically normal appearing anterior corneal surface.

- Associated ocular features (optic disc coloboma, congenital cataract, etc.).

- Abnormalities on corneal topography such as:

- Anterior corneal steepening (in cases of localized central PKC).

- Anterior corneal flattening (in cases of peripheral PKC).

Symptoms

Patients may be asymptomatic or may note long standing decreased vision in the affected eye.

Clinical Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made clinically based upon characteristic slit lamp findings and results of ancillary testing.

Diagnostic procedures

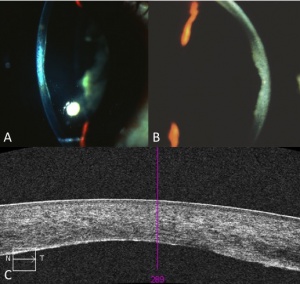

In addition to a thorough history and slit lamp exam, various ancillary tests can be performed to aid in the diagnosis. These diagnostic procedures include:

- Gonioscopy

- Pachymetry

- Corneal topography

- Ultrasound biomicroscopy

- Anterior segment optical coherence tomography

- Scheimpflug tomography

Testing

Although no genetic locus has been identified, genetic testing can be considered for research purposes or when concurrent systemic abnormalities suggest a syndromic etiology. Certain systemic abnormalities that have been associated with PKC include genitourinary malformations, thyroid abnormalities, and mental retardation. Thus, a systemic evaluation as well as laboratory testing, such as thyroid function testing, may identify such abnormalities.

Differential diagnosis

- Keratoconus

- Pellucid marginal degeneration

- Peters' anomaly

- Corneal scar (i.e. from trauma or infection)

Management

In pediatric patients, treatment should focus on amblyopia prevention as PKC can result in anisometropic amblyopia secondary to astigmatism or deprivation amblyopia from an associated corneal opacity.[16][17][18] As expected, unilateral eye involvement is more likely to result in amblyopia than bilateral involvement. Amblyopia prevention strategies include patching of the unaffected eye, refractive glasses or rigid contact lenses for astigmatism correction, and pupillary dilation or surgical intervention for corneal opacity.[13][19][20] PKC can be associated with other ocular abnormalities which may also result in decreased visual acuity so it is important patients are screened and then treated appropriately to maximize visual acuity and prevent the development of amblyopia.

For adult patients and pediatric patients no longer at risk for amblyopia, the main treatment involves refractive spectacles and/or a trial of rigid contact lenses. Keratoplasty may also be considered if it is felt that the corneal opacity is obstructing the visual axis and resulting in decreased visual acuity.

Special attention should be paid to patients with PKC undergoing cataract surgery. In particular, pre-operative biometry testing and intraocular lens (IOL) power calculation formulas may overestimate the total corneal power due to irregularities in the corneal curvature that are not accounted for.[21] In order to avoid a hyperopic surprise, both anterior and posterior corneal curvature values should be measured and included in IOL power calculation before surgery.

Medical therapy

In PKC patients with associated systemic abnormalities, the primary care physician should be involved in the screening and treatment of these problems.

Medical follow up

In the pediatric patient population, frequent follow-up is indicated to monitor and potentially treat amblyopia. The timing of follow-up is at the discretion of the treating ophthalmologist based upon the severity of amblyopia and need for intervention.

As PKC is generally non-progressive, in the adult population, follow-up will vary based upon concurrent ocular pathology. For example, in patients with PKC associated with iridocorneal adhesions, regular IOP checks may be necessary to monitor for the presence of glaucomatous changes. However, in adult patients with isolated PKC, it is reasonable to follow patients on a routine annual basis.

Surgery

In pediatric patients with visually significant corneal opacity that is not amenable to pupillary dilation, surgical intervention may be warranted to prevent amblyopia. Central and paracentral PKC with corneal clouding can be treated similar to other congenital corneal opacity with optical sector iridectomy, rotational corneal autograft or penetrating keratoplasty (PKP).[20]

In adults with PKC and large central opacity, visual acuity may be limited by longstanding amblyopia and caution should be taken prior to pursuing surgical intervention.

Prognosis

As PKC is generally non-progressive, patients with mild corneal opacification, no associated ocular abnormalities, or coexisting amblyopia, the general prognosis can be good. Early diagnosis and appropriate management are important.

References

- ↑ ROSS JV. Keratoconus posticus generalis. Am J Ophthalmol 1950;33:801–3.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Rao SK, Padmanabhan P. Posterior keratoconus. An expanded classification scheme based on corneal topography. Ophthalmology 1998;105:1205–12.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 al-Hazzaa SA, Specht CS, McLean IW, et al. Posterior keratoconus. Case report with scanning electron microscopy. Cornea 1995;14:316–20.

- ↑ Haney WP, Falls HF. The occurrence of congenital keratoconus posticus circumscriptus in two siblings presenting a previously unrecognized syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1961;52:53–7.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Krachmer JH, Rodrigues MM. Posterior keratoconus. Arch Ophthalmol 1978;96:1867–73.

- ↑ Wolter JR, Haney WP. Histopathology of keratoconus posticus circumscriptus. Arch Ophthalmol 1963;69:357–62.

- ↑ Jacobs HB. Traumatic keratoconus posticus. Br J Ophthalmol 1957;41:40–1.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Streeten BW, Karpik AG, Spitzer KH. Posterior keratoconus associated with systemic abnormalities. Arch Ophthalmol 1983;101:616–22.

- ↑ Greene PB. Keratoconus posticus circumscriptus. Arch Ophthal 1945;34:432–3.

- ↑ Charan H. Keratoconus posticus circumscriptus with indentation of the lens. Br J Ophthalmol 1967;51:486–8.

- ↑ KARLIN GN, Wise GN. Keratoconus posticus. Am J Ophthalmol 1961;52:119–21.

- ↑ Forsius H, Metsälä P. Keratoconus Posticus. Acta Ophthalmol 1963;41:768–76.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Silas MR, Hilkert SM, Reidy JJ, Farooq AV. Posterior Keratoconus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018 Jul;102(7):863-867.

- ↑ Williams R. Acquired posterior keratoconus. Br J Ophthalmol 1987;71:16–17.

- ↑ Bareja U, Vajpayee RB. Posterior keratoconus due to iron nail injury--a case report. Indian J Ophthalmol 1991;39:30.

- ↑ Mannis MJ, Lightman J, Plotnik RD. Corneal topography of posterior keratoconus. Cornea 1992;11:351–4.

- ↑ Chan DQ. Bilateral circumscribed posterior keratoconus. J Am Optom Assoc 1999;70:581–6.

- ↑ Charles N, Charles M, Croxatto JO, et al. Surface and Orbscan II slit-scanning elevation topography in circumscribed posterior keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005;31:636–9.

- ↑ Young ID, Macrae WG, Hughes HE, et al. Keratoconus posticus circumscriptus, cleft lip and palate, genitourinary abnormalities, short stature, and mental retardation in sibs. J Med Genet 1982;19:332–6.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 Garg N, Chang TC, Reiser BJ, et al. A novel characterization of posterior keratoconus using anterior segment optical coherence tomography in an infant: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol 2015;15:158.

- ↑ Tamaoki A, Kojima T, Hasegawa A, et al. Intraocular lens power calculation in cases with posterior keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 2015;41:2190–5.