Periocular (Periorbital) Dermatitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

- ICD-9-CM 373.32 - Contact and allergic dermatitis of eyelid

- ICD-10-CM H01.119 - Allergic dermatitis of unspecified eye, unspecified eyelid

- ICD-9-CM 373.31 - Eczematous dermatitis of eyelid

- ICD-10-CM H01.139 - Eczematous dermatitis of unspecified eye, unspecified eyelid

Disease

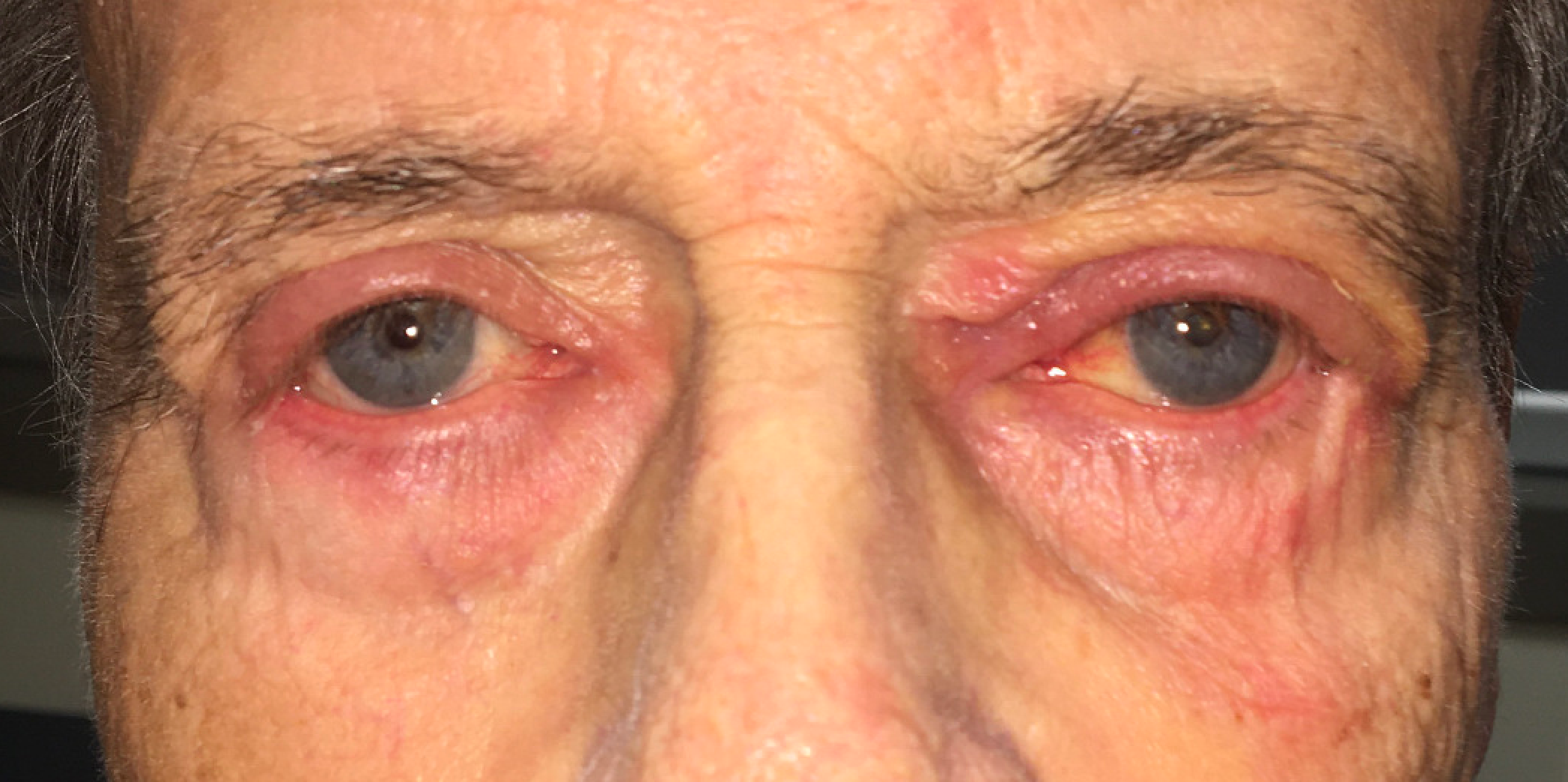

Periocular dermatitis, also known as periorbital dermatitis, is a common dermatological disorder characterized by inflammation of the eyelids and the skin surrounding the eyes.

Etiology

There are a variety of possible etiologies, including:

- Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD)

- Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD)

- Airborne contact dermatitis

- Atopic dermatitis

- Psoriasis

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Nonspecific xerotic dermatitis

Epidemiology

Periocular dermatitis is a common skin complaint, and is present in 3.9% to 4.8% of patients presenting for patch testing.[1] Women are more commonly affected than men, making up 73-80% of cases. This disparity has been attributed to the use of cosmetic products, which is more common among women.[2] The single most common cause of periocular dermatitis is allergic contact dermatitis, to which 31-72% of cases can be attributed.[1],[3] Another 14-39.5% of cases are due to atopic dermatitis. Irritant contact dermatitis makes up only 7-9% - this is in contrast to the body as a whole, in which irritant contact dermatitis accounts for 70-80% of all contact dermatitis causes.[4] Among the most common reasons for contact dermatitis that affects the eyelids is the use of hair dye, especially those that contain p- phenylenediamine.[5]

Risk Factors

- Female sex

- Age >40 years

- Atopic eczema

- Asthma

- Hayfever (“atopy”)

- CARD11 gene mutations

- FLG gene mutations

General Pathology

Histologic sampling is generally reserved only for cases in which an underlying malignancy is suspected, such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. If a biopsy is taken, histologic findings will vary depending on disease etiology, but usually demonstrates non-specific inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes. ACD is associated with spongiosis and exocytosis on histology, whereas epidermal necrosis may be seen with ICD.[4]

Pathophysiology

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is by far the most common cause of periocular dermatitis.[1] Type IV hypersensitivity responses may be induced by a variety of allergens, including ingredients commonly found in eye makeup and perfumes. These include resins, solvents, volatile oils, preservatives, and pigment. Neomycin is also commonly observed to cause contact dermatitis, largely due to its frequent use among the general population allowing sensitization. High rates of neomycin allergy have contributed to many surgeons reluctance to use it post-procedurally, however there is some evidence that neomycin, polymyxin B, and dexamethasone ophthalmic ointment can be used in this regard with lower rates of allergic reaction than would be expected.[6] Additionally, several of the preservatives often used in ophthalmologic ointments have been identified as allergens, including methylparaben, propylparaben, phenylmercuric acetate, and (less commonly today) thimerosal. While nickel allergy is the most common Type IV hypersensitivity overall, and nickel may be a component of certain cosmetics, it may play a lesser role in the prevalence of periocular dermatitis.[1]

Airborne contact dermatitis can be considered a subset of the allergic contact dermatitis category, with the distinction that the allergen is a volatile or aerosolized substance. This includes air fresheners, nail polish, paint fumes, and glues, as well as innumerable natural and synthetic substances that may be encountered in daily life. As much of the rest of the body’s skin is either thicker or covered by clothing, the periocular area is often the only skin affected. Allergic contact dermatitis may also be initiated by plant or animal proteins. Common triggers include pollen, dust mites, animal hair, and latex. Airborne etiologies are relatively common and account for up to a fifth of allergic contact dermatitis cases.[2]

Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) is caused by injury to the skin due to friction, temperature, or chemicals such as acids, alkalis, detergents, and solvents. While it accounts for 70-80% of contact dermatitis as a whole, irritant contact dermatitis plays a lesser role in periocular region as this area has less contact with these irritants than the hands or arms.[7]

Atopic dermatitis (eczema) can also cause periocular dermatitis and should be suspected when patients present with other components of the “atopic triad” of asthma and allergies. The pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis involves multiple factors, including breakdown of the epidermal barrier, abnormal skin microbial flora, and immune dysregulation.

All the above processes may contribute to impaired barrier function, often leading to bacterial or fungal superinfection. This may make treatment difficult, due to infection as well as sensitization to the microorganisms themselves.[8][9][10] Additionally, multifactorial presentations are common, such as when a patient becomes sensitized to an agent that initially caused an irritant contact dermatitis and subsequently develops an allergic contact dermatitis.[8]

Diagnosis

History

A thorough history can sometimes identify the offending agent. Patients should be questioned thoroughly regarding their skincare and makeup routines and asked to identify any new products. As allergens and irritants can easily be transferred from the hand to the eye by rubbing, patients should also be asked about any recent exposure to chemicals or plant materials, new nail polishes, or contact with any aerosolized agents. Patients work routines should also be covered if an occupational exposure is suspected. Finally, a thorough mediation review should be performed, as topical eye drops (such as beta blockers used to treat glaucoma) have been known to cause periocular dermatitis.[11] Brimonidine eye drops are another frequent cause of periocular dermatitis.

Timing of onset can also play a role in diagnosis: ACD typically occurs within a 24-96 hour window following contact with the allergen, whereas ICD appears rapidly following exposure to the irritant.[4] A history of ICD in response to a known irritant does not guarantee that the patient will respond with ICD again, as they have now been sensitized and further exposure has potential to initiate an ACD response.

Physical examination

The subgroups of periocular dermatitis have varying presentations, and clinical appearance alone is not diagnostically conclusive.[2] However, there are several findings which are classically observed and may help differentiate between ACD and ICD. In some cases the rash associated with ACD will have defined borders, however spreading is common and sites far from the initial rash may be affected. A typical presentation may involve erythema with papules and vesicles. Vesicles may progress to oozing and crusting, with chronic exposure leading to lichenification. In contrast, the rash classically associated with ICD is limited to the area directly exposed to the irritant. Appearance can vary depending on the offending agent and ranges from xerosis to burns, however most cases appear as erythematous macules or papules.

Symptoms

The chief compliant of patients with periocular dermatitis is usually redness surrounding the eye, with or without involvement of the eyelid. The location, laterality, and distribution of redness may provide clues as to the offending agent in cases of ACD or ICD. For example, nickel allergy induced by the patient’s eyeglasses may result in erythema near the cheek and eyebrow while sparing the eyelids, and a reaction to components in mascara may be localized to only the eyelids. Contact dermatitis etiologies are also associated with some degree of discomfort: ICD patients classically describe a “burning” sensation, whereas ACD is more associated with itching.

Clinical diagnosis

The general appearance of periocular dermatitis is usually easily recognizable, therefore a preliminary clinical diagnosis can often be made based on examination alone. However, determination of the etiology of the patient’s condition usually requires further investigation.

If a particular cosmetic product is suspected of causing ACD, the repeated open application test (ROAT) can be performed easily. The patient is instructed to apply the product to a small area of sensitive skin (such as the inner forearm or behind the ear) twice daily for 5-7 days and self-monitor for redness or swelling. This test is useful due to its simplicity, but has reduced sensitivity when investigating the periocular region as thicker skin found elsewhere in the body may not react as severely to the agent.

Patients may benefit from referral to an allergy specialist for more intensive patch testing if the offending agent cannot be determined from their history.[12] Patch testing suffers from the same issues as ROAT: truncal skin may not be as susceptible to allergens as the periocular region. Additionally, conventional patch testing may not detect allergens found in the patient’s ocular medications, therefore direct application of the patient’s individual medications may be required to determine the source of the allergen.[13] Alternative patch testing methods, such as tape stripping, enlarged testing areas, or high-concentration agents may improve sensitivity, but can also result in a higher false positive rate due to irritation of the skin.[14]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of periocular dermatitis includes allergic contact dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, airborne contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, nonspecific xerotic dermatitis, rosacea, acne vulgaris, periocular cellulitis, carcinoid syndrome, and lupus erythematosus.

Management

General treatment

Treatment of most cases of periocular dermatitis revolves around avoidance of any triggering agents and symptomatic relief with topical medications. Regardless of whether an offending agent can be identified based on the patient’s history, all periocular use of cosmetics and skin products should be suspended.

If ROAT or patch testing identifies a causative allergen, the patient can be advised to gradually reinstitute their makeup or skin regimen, with exclusion of the allergen. Prior to adding new products, patients can be advised to apply the substance to their neck or forearm for 5-7 days prior to facial application to check for a reaction.[3] For cases of beta-blocker-induced dermatitis, the medication should be discontinued and the patient should be started on an alternative topical glaucoma medication.[11] Eligible patients may be referred for surgical management of glaucoma.

The patient should also be educated to help them avoid the allergen or irritant in the future. Multiple resources are available to provide patients with information on product ingredients and how to avoid various compounds (see Additional Resources).

Medical therapy

Topical corticosteroids such as hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, loteprednol, fluoromethalone, prednicarbate, and mometasone may be used short-term for mild cases of periocular dermatitis. Steroids are not suitable for long term treatment due to the risk of side effects including skin atrophy, adrenal suppression, and sensitization to the steroid itself. In addition, topical steroids may increase the risk of glaucoma, cataract, and other ocular disease.[15] Once symptoms have improved the steroid should be discontinued, however it may be necessary to taper the dose to prevent rebound dermatitis. In addition, it is very important to avoid long-term use of topical corticosteroids in the periocular region as it may lead to the development of increase intraocular pressure or even glaucoma.[16]

Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as pimecrolimus and tacrolimus are approved to treat atopic dermatitis and have also been used with good results to treat other causes of periocular dermatitis, including ACD, ICD, seborrheic dermatitis, and psoriasis.[2],[17],[18] They may be used safely in the periocular area and have a favorable side effect profile, but are less effective than steroids in short-term treatment. Some practitioners prefer to initiate treatment with a calcineurin inhibitor and reserve topical steroids for refractory cases.[2]

A variety of other treatments have been used, including zinc-compound masks and astringent tea compresses.[2] In some cases antibiotics such as tetracyclines and macrolides may be used, particularly if a microbial superinfection is suspected.[19] There are also several reports of successful treatment with oral and topical calcitriol or paricalcitriol in patients with refractory or severe atopic dermatitis.[20][21]

Prognosis

Periocular dermatitis typically has a good prognosis, with most cases resolving within one month of treatment.[11] For cases of ACD and ICD, relapse depends on the successful identification of the causative agent and subsequent avoidance of it. Other causes of periocular dermatitis such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis may be more difficult to treat, with recurring episodes requiring multiple rounds of treatment.

Additional Resources

- Allergens in Cosmetics. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredients/allergens-cosmetics. Accessed 6/7/20.

- Bala HR, Cahill J, Nixon RL, Periocular Dermatitis. DermNet NZ. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/periocular-dermatitis/

- Patient Info Series. Dormer Laboratories Inc. http://www.dormer.com/Allergens/PatientInfoSeriesEng.aspx Accessed 6/7/20.

- What’s in It? Consumer Product Information Database. https://www.whatsinproducts.com/types/index/1 Accessed 6/7/20.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Feser A, Plaza T, Vogelgsang L, Mahler V. Periorbital dermatitis—a recalcitrant disease: causes and differential diagnoses. British Journal of Dermatology. 2008;159(4):858-863. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08790.x

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Feser A, Mahler V. Periorbital dermatitis: Causes, differential diagnoses and therapy. JDDG: Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft. 2010;8(3):159-165. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.07216.x

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Guin JD. Eyelid dermatitis: Experience in 203 cases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2002;47(5):755-765. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.122736

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Nosbaum A, Vocanson M, Rozieres A, Hennino A, Nicolas J-F. Allergic and irritant contact dermatitis. European Journal of Dermatology. 2009;19(4):325-332. doi:10.1684/ejd.2009.0686

- ↑ Gupta M, Mahajan VK, Mehta KS, Chauhan PS. Hair dye dermatitis and p-phenylenediamine contact sensitivity: A preliminary report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015 Jul-Aug;6(4):241-6. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.160253. PMID: 26225326; PMCID: PMC4513401.

- ↑ Moore NA, Czyz CN, Carter TD, Foster JA, Cahill KV. Neomycin, polymyxin B, and dexamethasone allergic reactions following periocular surgery. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2017;7. doi:10.1186/s12348-017-0133-4

- ↑ Shah M, Lewis F, Gawkrodger D. Facial dermatitis and eyelid dermatitis: a comparison of patch test results and final diagnoses. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:140-141.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Temesvári E, Pónyai G, Németh I, Hidvégi B, Sas A, Kárpáti S. Periocular dermatitis: a report of 401 patients. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2009;23(2):124-128. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02949.

- ↑ Tengvall Linder M, Johansson C, Scheynius A, Wahlgren C. Positive atopy patch test reactions to Pityrosporum orbiculare in atopic dermatitis patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30(1):122-131. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00702

- ↑ Gupta AK, Kohli Y, Summerbell RC, Faergemann J. Quantitative culture of Malassezia species from different body sites of individuals with or without dermatoses. Med Mycol. 2001;39(3):243-251. doi:10.1080/mmy.39.3.243.251

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Chisholm SAM, Couch SM, Custer PL. Etiology and Management of Allergic Eyelid Dermatitis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(4):248-250. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000723

- ↑ Landeck L, John SM, Geier J. Periorbital dermatitis in 4779 patients – patch test results during a 10-year period. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;70(4):205-212. doi:10.1111/cod.12157

- ↑ Herbst RA, Uter W, Pirker C, Geier J, Frosch PJ. Allergic and non-allergic periorbital dermatitis: patch test results of the Information Network of the Departments of Dermatology during a 5-year period. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51(1):13-19. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.00334.

- ↑ Landeck L, Schalock PC, Baden LA, Gonzalez E. Periorbital Contact Sensitization. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2010;150(3):366-370.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2010.03.026

- ↑ Sahni, D., Darley, C. R., & Hawk, J. L. M. (2004). Glaucoma induced by periorbital topical steroid use–a rare complication. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology: Clinical dermatology, 29(6), 617-619.

- ↑ Maeng, M. M., De Moraes, C. G., Winn, B. J., & Glass, L. R. D. (2019). Effect of topical periocular steroid use on intraocular pressure: a retrospective analysis. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, 35(5), 465-468.

- ↑ Kang S, Paller A, Soter N, Satoi Y, Rico MJ, Hanifin JM. Safe treatment of head/neck AD with Tacrolimus ointment. Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 2003;14(2):86-94. doi:10.1080/09546630310004324

- ↑ Mensing CO, Mensing CH, Mensing H. Treatment with pimecrolimus cream 1% clears irritant dermatitis of the periocular region, face and neck. International Journal of Dermatology. 2008;47(9):960-964. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03634.

- ↑ Fisher AA. Periocular dermatitis akin to the perioral variety. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1986;15(4):642-644. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(86)70218-1

- ↑ Tukaj S, Zillikens D, Kasperkiewicz M. Topically applied low-dose calcitriol ameliorates atopic eyelid dermatitis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;5(1):5-6. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.09.012

- ↑ Bothou C, Alexopoulos A, Dermitzaki E, et al. Successful Treatment of Severe Atopic Dermatitis with Calcitriol and Paricalcitol in an 8-Year-Old Girl. Case Reports in Pediatrics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9643543