Pellucid Marginal Corneal Degeneration

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Pellucid Marginal Degeneration (PMD) is a noninflammatory, nonhereditary cause of corneal ectasia with bilateral, clear, inferior (typically 4 o’clock to 8 o’clock), peripheral corneal thinning.

Disease Entity

PMD is uncommon and is characterized by a crescent-shaped band of inferior corneal thinning approaching 20% of normal thickness that is 1 to 2 mm in height, 6 to 8 mm in horizontal extent, and 1 to 2 mm from the limbus. There is no associated inflammation and the central cornea is of normal thickness.

Disease

PMD is disease of peripheral corneal thinning that is slowly progressive over many years. It is important to recognize as it can cause severe deterioration in visual function. Also, patients who undergo refractive surgery with PMD can have deleterious results, so it is important to consider prior to refractive surgery.

Etiology

The etiology of PMD remains unknown.

Risk Factors

PMD, while rare, is the second most common noninflammatory corneal thinning disorder after keratoconus. Some people postulate, however, that this prevalence might be underestimated as the condition is often misdiagnosed as keratoconus. Keratoconus, keratoglobus, and PMD are postulated to be related because these conditions coexist in families. Ten percent of PMD cases are associated with keratoconus and 13% are associated with keratoglobus. In series performed in Japan, 17 of 27 cases of unilateral PMD revealed keratoconus or suspected keratoconus in the fellow eye. It has not been elucidated whether keratoconus, keratoglobus, and PMD are different diseases or phenotypic variations of the same disease.

PMD typically presents in the second to fifth decade of life. PMD has no sex or racial predilection, and does not appear to be hereditary, but moderate to high astigmatism has been noted in families with affected patients. A recent case showed that PMD was coexistent with corneal plana in an individual with a KERA mutation, thus, potentially implicating KERA in the development of PMD.

General Pathology

Histopathologic abnormalities in PMD resemble keratoconus. Classically, PMD is histologically thought to show an area of stromal thinning, normal epithelium, endothelium, and Descemet's membrane, and absent or broken (focal disruption) Bowman's membrane. Lipid deposits are typically absent and stromal ground substance rich in mucopolysaccharides is present. Electron microscopy of the thin regions reveals unusual electron-dense areas of fibrous long-spacing (FLS) collagen with a periodicity of 100 to 110 nm, whereas normal collagen has a periodicity of 60 to 64 nm. FLS collagen has also been observed in advanced KC. In cases of acute hydrops, breaks in Descemet's membrane with swelling of the stroma and inflammatory infiltrate is seen.

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of PMD has not been ascertained, but it is thought to be secondary to collagen abnormalities, similar to keratoconus. The thin, weakened cornea is hypothesized to protrude as a result of intraocular pressure.

Primary Prevention

No preventative strategies exist for PMD. Given the corneal thinning and the potential association of eye rubbing with keratoconus and its relationship to PMD, it could be considered to advise patients not to rub their eyes.

Diagnosis

Pellucid gets its name from the meaning "transparent" as the cornea typically appears transparent in this degeneration. The diagnosis is made clinically as patient's are usually asymptomatic except for progressive visual deterioration.

History

Patients with PMD typically present asymptomatically except with progressive visual deterioration despite spectacle correction due to the irregular astigmatism. They someimes present with acute corneal hydrops and pain or acute decrease in vision, but this is relatively rare with only a few case reports.

Physical Examination

Slit lamp examination is typically characterized by a peripheral band of corneal thinning in the inferior cornea from 4 to 8 o'clock. The thinning can reach 20% of normal corneal and is 1 to 2 mm from the limbus. The steepest corneal protrusion in PMD occurs above (central to) the area of stromal thinning, appearing like a "beer belly" in cross section. This results in high and irregular "against-the-rule" astigmatism of up to 20 diopters and a flattening of the vertical meridian. The astigmatism can instead be "with the rule" if the inferior curvature is steeper than the horizontal curvature. The area of thinning in PMD is always epithelialized, clear, avascular, and without lipid deposition (distinguishing it from Terrien marginal degeneration). Prominent lymphatics are also associated with PMD at the inferior limbus parallel to the area of thinning.

Vertical striations at the level of the Descemet membrane (similar to Vogt striae), hydrops, vascularization, and scarring are relatively rare, as is spontaneous corneal perforation. The ectasia and thinning can also occur superiorly. PMD does not present with an iron ring, cone, apical scarring, or abnormal corneal sensation. Descemet’s folds can develop concentric to the inferior limbus and posterior stromal scarring can be noted in the thin areas.

Signs

Signs of PMD include:

- Inferior corneal thinning

- Severely reduced uncorrected visual acuity that typically cannot be improved with spherocylinder lens

- Practically normal pinhole visual acuity

- Refraction and keratometry showing against-the-rule astigmatism

Symptoms

Patients typically report a gradual decrease in vision uncorrected by spectacles.

Clinical Diagnosis

PMD is a clinical diagnosis based primarily on the slit lamp examination and history and supported by corneal topography/tomography.

Diagnostic procedures

Several tests exist to assist with the detection and early diagnosis of PMD:

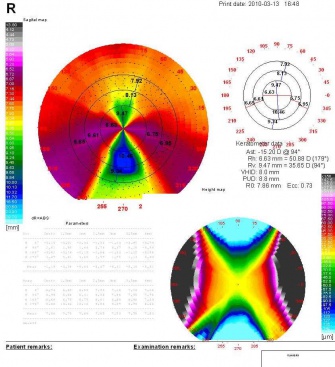

- Corneal topography/tomography

- Computerized videokeratography: Shows a classic "butterfly" appearance with PMD, showing low power along the central vertical axis, increasing power in the inferior cornea and high power along the infero-oblique meridians

- Pachymetry: Used to measure for inferior corneal thinning, which is a reversal of the typical pattern in which the cornea thickens from center to periphery

- Orbscan: Shows a classic "kissing birds" appearance with PMD

Laboratory test

No laboratory tests exist at this time for PMD.

Differential diagnosis

- Keratoconus

- Keratoglobus

- Terrien marginal degeneration

- Furrow degeneration

- Peripheral corneal melting disorders (for example, Mooren ulcer)

Management

Management with PMD is difficult given the abnormal corneal topography and degree of corneal protrusion. Management is typically with either spectacles, contact lenses, or surgery.

General treatment

Because of extremely abnormal corneal topography, the treatment of PMD is difficult. Therapeutic options are limited by the degree of corneal protrusion. A recent study at a tertiary care center found that 88% of PMD cases were managed nonsurgically with spectacles (36%) or contacts (52%), whereas 12% underwent penetrating keratoplasty.

Medical therapy

The standard medical therapy is contact lens correction. Spectacle correction typically fails early in the course of PMD with the increasing astigmatism.

Contact lens (CTL) correction can be attempted when corneal ectasia is mild, but inferior decentration often makes proper contact lens fit difficult, more difficult than with keratoconus. Hybrid (gas-permeable lenses with a soft lens skirt) or scleral lens can also be considered.

The specific types of contact lens for mild PMD and their pros/cons are listed below:

- Toric hydrophilic CTL: spherical hydrophilic CTL are not useful given the associated astigmatism

- Hybrid CTL: they are easier to fit on patients, but their low oxygen permeability can result in corneal neovascularization

- Rigid gas permeable CTL: provide good oxygenation of the cornea but are hard to fit. Can sometimes place in the upper eyelid with large-diameter lens, but this can cause irritation and can move excessively

All of these CTL treatments are symptomatic treatments to improve the patient's visual acuity and can result in flare and decreased contrast sensitivity. There is no evidence that these lens prevent progression of the disease.

Medical follow up

PMD is slowly progressive and be followed at regular, extended intervals.

Surgery

If medical therapy is unsatisfactory, surgical treatment may be required to restore vision or due to patient intolerance of contact lens. Clasically, this surgical treatment has been penetrating keratoplasty. However, for PMD, this requires large (9.0 mm or larger), inferiorly decentered penetrating keratoplasty grafts for highly ectatic cases. The transplant's large graft size and its location near the limbus increases the risk of vascularization and corneal graft rejection and is more surgically challenging. Regular-sized grafts deliberately decentered inferiorly are also suboptimal due to the large degree of astigmatism and high incidence of rejection.

Other surgical procedures have been advocated include:

- Diathermy

- Lamellar keratoplasty

- C-shaped lamellar keratoplasty

- Thermokeratoplasty

- Lamellar crescentic resection of the affected area and re-apposition of normal thickness cornea from each side of the affected area

- Wedge resection

- Full-thickness crescentic resection

- Replacement by a freehand corneoscleral graft

- Tectonic lamellar grafting followed by a central penetrating keratoplasty

- Large epikeratophakia graft

- Intrasomal ring segment implantation using a femtosecond laser to make lamellar dissections

- Intracorneal ring segments and bitoric or intralimbal rigid gas-permeable lenses may also improve vision.

Recently, the most favored treatment has been a peripheral lamellar crescentic keratoplasty followed by a central penetrating keratoplasty. Some have even advocated for performing both procedures simultaneously, but this is technically challenging.

Surgical follow up

Surgical follow-up depends on the surgical procedure performed. Corneal grafts require ongoing monitoring for failure, rejection, glaucoma, and other complications.

Complications

Complications can occur with PMD, but are more rare than keratoconus. Complications that occur include vertical stress lines and acute hydrops, but these are relatively rare. Spontaneous corneal perforation has also been reported. Vascularization and scarring of the cornea can occur but typically the cornea is clear without neovascularization or lipid deposition. Descemet’s folds can develop as can posterior stromal scarring.

Prognosis

PMD is slowly progressive over many years and results often in severe visual deterioration of working age people. No large longitudinal studies have been reported, with the largest study following 31 patients over 8 years and noting that 5 required corneal transplantation in one eye and 1 requiring transplantation in both eyes.

Additional Resources

A helpful Web site for patients regarding PMD is: http://www.lensdesign.ca/pmd.htm

There are several other useful keratoconus Web sites, and given that many PMD patients are misdiagnosed, there groups often discuss and have information on PMD: www.nkcf.org/

References

1. Jain A, Paulus YM, Cockerham GC, Kenyon KR. Keratoconus and Other Non- inflammatory Thinning Conditions. Duane's Foundations of Clinical Ophthalmology Vol 4, Chapter 16C. Ed. William Tasman, MD and Edward A. Jaeger, MD. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkens, 2008.

2. Karabatsas CH, Cook SD: Topographic analysis in pellucid marginal corneal degeneration and keratoglobus. Eye 10:451–455, 1996

3. Krachmer J: Pellucid marginal corneal degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 96:1217–1221, 1978

4. Maguire L, Klyce SD, McDonald MB, Kaufman HE: Corneal topography of pellucid marginal degeneration. Ophthalmol 94:519–524, 1987

5. Sridhar M, Mahesh S, Bansal AK et al: Pellucid marginal corneal degeneration. Ophthalmol 111:1102–1107, 2004

6. Kayazawa F, Nishimura K, Kodama Y et al: Keratoconus with pellucid marginal corneal degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 102:895–896, 1984

7. Santo RM, Bechara SJ, Kara-Jose N: Corneal topography in asymptomatic family members of a patient with pellucid marginal degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 127:205–7, 1999

8. Nagy M,, Vigvary L: Etiology of the pellucid marginal degeneration of the cornea. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 161:604–611, 1972

9. Khan A, Aldahmesh M, Al-Saif A, Meyer B: Pellucid marginal degeneration coexistent with cornea plana in one member of a family exhibiting a novel KERA mutation. Br J Ophthalmol 89:1538–1540, 2005

10. Rodrigues M, Newsome DA, Krachmer JH, Eiferman RA: Pellucid marginal corneal degeneration: A clinicopathologic study of two cases. Exp Eye Res 33:277–288,1981

11. Gruenauer-Kloevekorn C, Fischer U, Kloevekorn-Norgall K, Duncker GI: Pellucid marginal corneal degeneration: evaluation of the corneal surface and contact lens fitting. Br J Ophthalmol 90:318–323, 2006

12. Tzelikis P, Cohen EJ, Rapuano CJ et al: Management of pellucid marginal corneal degeneration. Cornea 24:555–560, 2005

13. Rasheed K, Rabinowitz YS: Surgical treatment of advanced pellucid marginal degeneration. Ophthalmol 107:1836–1840, 2000

14. Speaker M, Arentsen JJ, Laibson PR: Long-term survival of large diameter penetrating keratoplasties for keratoconus and pellucid marginal degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl 192:17–19, 1989

15. Cheng C, Theng JT, Tan DT: Compressive C-shaped lamellar keratoplasty: A surgical alternative for the management of severe astigmatism from peripheral corneal degeneration. Ophthalmol 112:425–430, 2005

16. Cameron J: Results of lamellar crescentic resection for pellucid marginal corneal degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 113:296–302, 1992

17. Fronterre A, Portesani GP: Epikeratoplasty for pellucid marginal corneal degeneration. Cornea 10:450–453, 1991

18. Ertan A, Bahadir M: Intrastromal ring segment insertion using a femtosecond laser to correct pellucid marginal corneal degeneration. J Cataract Refract Surg 32:1710–1716, 2006

19. Rodriguez-Prats J, Galal A, Garcia-Lledo M et al: Intracorneal rings for the correction of pellucid marginal degeneration. J Cataract Refract Surg 29:1421–1424, 2003

20. Barbara A, Shehadeh-Masha'our R, Zvi F, Garzozi HJ: Management of pellucid marginal degeneration with intracorneal ring segments. J Refract Surg 21:296–298, 2005

21. Mularoni A, Torreggiani A, di Biase A et al: Conservative treatment of early and moderate pellucid marginal degeneration: a new refractive approach with intracorneal rings. Ophthalmol 112:660–666, 2005

22. Akaishi L, Tzelikis PF, Raber IM: Ferrara intracorneal ring implantation and cataract surgery for the correction of pellucid marginal corneal degeneration. J Cataract Refract Surg 30:2427–2430, 2004

23. Dominguez C, Shah A, Weissman BA: Bitoric gas-permeable contact lens application in pellucid marginal corneal degeneration. Eye Contact Lens 31:241–243, 2005

24. Ozbek Z, Cohen EJ: Use of intralimbal rigid gas-permeable lenses for pellucid marginal degeneration, keratoconus, and after penetrating keratoplasty. Eye Contact Lens 32:33–36, 2006

25. Shimazaki J, Maeda N, Hieda O, et al: National Survey of pellucid marginal corneal degeneration in Japan. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2016:60(5):341-8.