Orbital Lymphangioma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Definition

Lymphangiomas, also known as lymphatic malformations, are multi-cystic, localized malformations that involve the lymphatic and vascular systems, most commonly occurring in the head and neck region of pediatric patients.

Prevalence

The prevalence of lymphangiomas has been estimated to be 1.1 to 5.3 cases per 10,000 live births. However, the prevalence appears to be higher when the studies include terminated pregnancies and still-births: then, the estimate is 30 cases per 10,000.[1] Lymphangiomas represent around 4% of all vascular tumors and approximately 25% of benign pediatric vascular tumors.[2] Orbital lymphangiomas have a prevalence of 1.1 to 5.3 cases per 10,000 live births with an equal incidence between males and females.[1][3]

Classification

Lymphangiomas can be classified in three ways: a) blood flow type, b) vascular lesion type, c) cyst size and depth. These characterizations are helpful in predicting what forms of treatment may be successful.

The blood flow classification system was developed by the International Orbital Society. In this classification system, vascular malformations are separated into three distinct categories based on blood flow:

- No Flow Malformations (Type 1)

- Venous Flow Malformations (Type 2)

- Arterial Flow Malformations (Type 3)

Due to the fact that orbital lymphangiomas generally have minimal internal blood flow and an absence of connection to the vascular system, they can be classified as No Flow (Type 1) malformations. Examples of the other classifications include primary orbital varices for Venous Flow malformations (Type 2) and arteriovenous malformations for Arterial Flow malformations (Type 3).[4]

Along with classification based on the type of blood flow, lymphangiomas can also be classified based on the type of vascular lesion: venous, arterial, or lymphatic. In this classification, the malformation is categorized based on the predominant component (for example ‘venous dominant’ vs. ‘lymphatic dominant’).[5]

Finally, classification can be made based on the cyst size and depth. Lesions can be categorized as microcystic (<2cm), macrocystic (>2cm cysts), and mixed.[6] For depth classification, lesions are classified into:

- superficial

- deep: characteristics of orbital infiltration

- combined (both superficial and deep components)

- complex (intracranial or head and neck infiltration)[7]

Pathophysiology

Lymphangiomas are generally either congenital or acquired. The congenital form is due to an improper connection of lymphatic channels to the main lymphatic draining duct. Acquired lymphangiomas can occur following the interruption of lymphatic drainage through various mechanisms including surgery, trauma, malignancy, or radiation therapy.[8]

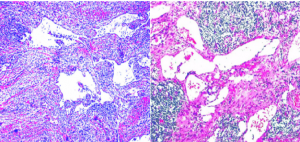

Histology

Histopathological analysis of lymphangiomas generally consist of large lymphatic cisterns that lie in the subcutaneous plane and communicate via dilated dermal lymphatic channels which are lined with endothelial cells.[8] These lesions, often of macrocystic or microcystic nature often demonstrate large, irregular vascular spaces that are lined with a single layer of endothelial cells located within a fibroblastic or collagenous stroma. [8]

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

For orbital lymphangiomas, presentation is usually in childhood; 43% are diagnosed before the age of 6 years old and 60% before the age of 16 years old.[3] The most frequent presenting features of orbital lymphangiomas are proptosis and ptosis of the affected eye. Other presentations include periocular mass and physical disfigurement, restriction of extraocular movements, mechanical blepharoptosis, and compressive optic neuropathy.[7] In a retrospective study of 26 patients with orbital lymphangioma 85% of patients had proptosis, 73% had ptosis and 46% had a restriction in ocular motility.[9] These symptoms are often not clinically present until an inciting factor causes an increase in size of the lesion. This is often due to mild trauma (seen in infants) causing hemorrhage into the lesion or acute upper respiratory infection leading to swelling of the lesion.[7][10]

Presenting symptoms, such as ptosis and physical disfigurement, are extremely important to monitor in infants and children as they can obstruct visual development and lead to amblyopia. Additionally, acute increase in mass size from hemorrhage or acute URI can damage vision. Preservation of vision and prevention of amblyopia are key priorities.

Diagnostic Procedures

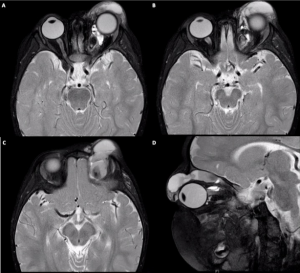

Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation and radiologic findings. CT scan demonstrates cyst-like masses with varying degrees of enhancement along with rim enhancement of cysts with hemorrhage.

On MRI, orbital lymphangiomas are generally isointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2 images, often with a presence of internal septations within the lesion.[10]

Pathognomonic findings include multiple cysts with air-fluid levels .

Radiology aids in diagnosis of lymphangioma and allows assessment of the size of the lesion and the extent of involvement of surrounding structures. This guides management. For example, depth influences ease of intervention with superficial lesions being easier to treat than deeper ones. A deep, asymptomatic lesion may be observed over a more superficial one, which can potentially be treated with less risk to surrounding structures. Size also influences type of intervention with larger cysts, typically larger than 2cm, being better candidates for sclerotherapy.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for orbital lymphangioma encompasses the differential for an orbital mass including:

Vascular:

- Cavernous hemangioma

- Hemangiopericytoma

- Lymphangioma / Lymphatic Malformation

- Venous malformation

- Arterio-venous fistula

- Orbital hemorrhage

Neural:

- Schwannoma

- Meningioma

- Optic nerve glioma

- Neurofibroma

Malignant / Metastasis:

- Lymphoma

- Metastasis from lung cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, neuroblastoma, and leukemia

Management

The major management options fall into one of four categories: observation, intralesional sclerosant injection, systemic medication, and surgery. There are risk and benefits to all four treatment types and no clear gold standard. Currently, there are no randomized controlled trials comparing the various medical or surgical therapies used to treat this condition.[11]

Observation

In patients, who do not have vision threatening symptoms or severe physical disfigurement, observation of the lesion can be considered. This is due to the fact that complete excision is difficult with a high risk of morbidity and recurrence.[7][12]

Sclerotherapy

Sclerotherapy is an umbrella term that characterizes the multiple types of agents that are injected (usually under ultrasound guidance) into the cystic spaces of the lesion, leading to scar formation and reduction in the size of the cyst and lesion. Specific agents used in orbital lymphangiomas include OK-432 (Picinibil), sodium tetradecyl sulfate, doxycycline, ethanol, pingyangmycin, and bleomycin.

It is important to note that sclerotherapy has been reported to be effective in treating macrocystic lymphatic malformations (size >2cm), with less efficacy in microcystic malformations.[13] A 2016 prospective interventional study looked at 29 patients with macrocystic orbital lymphangiomas who underwent sclerotherapy injection with sodium tetradecyl sulfate. At an average follow-up time of 21.8 months, all patients showed a reduction in maximal lesion diameter of 50% or greater, with improved visual acuity in 78.2% and complete radiological resolution in 51.7%.[14] Similarly, a 2017 prospective interventional studied looked at 13 patients with orbital lymphangiomas who were underwent sclerotherapy injection with bleomycin. With an average follow up time of 19.69 months, 92% of patients showed a >60% reduction in the maximal lesion diameter.[10]

Risks of this procedure include infection, bleeding, damage of adjacent structures during injection, and post-injection reactive inflammation.

Medical therapy

Medical therapy often includes the use of either systemic sildenafil (PDE-5 inhibitor) or sirolimus (mTOR inhibitor) therapy.

Sildenafil Therapy

Sildenafil is a phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE-5) inhibitor, which leads to an increase in cyclic guanosine monophosphate in smooth muscles, leading to its vasodilatory effects. Lymphangiomas containing cysts are thought to dilate from contraction of the muscular lining of the lesions vascular channels. Therefore sildenafil is thought to relax these smooth muscle contracts, leading to a reduction in lesion size. The study of sildenafil treatment for orbital lymphangiomas is limited, with a 2013 retrospective case series showing the reduction of orbital and surrounding tissue (facial, eyelid, cheek) swelling in two pediatric patients who had previously underwent surgical and sclerotherapy procedures without success.[15]

In another study of patients with lymphangiomas of the head and neck region, a low dose of oral sildenafil citrate was shown to be a safe and effective method of decreasing the volume of macrocystic and mixed lesions. These malformations were shown to be reduced when using a dose of 1 mg/kg/day and increasing the dosage to 3 mg/kg/day, with longer-term usage (seven months).[16]

Sirolimus Therapy

Sirolimus is a mTOR inhibitor that prevents cell growth and proliferation, leading to a reduction in vascular endothelial growth factor production along with a reduction in IL-2. A reduction in these factors are proposed to play a role in the reduction of lymphangioma size.

In a 2016 case series, oral sirolimus therapy was shown to be effective both radiologically and in terms of functional impairment in patients with lymphangioma. Sirolimus has a strong response for malformations of the arterial-venous and venous-lymphatic type .

Dosing is generally 0.8 mg/ml with optimal trough levels falling within 10 ng/ml to 15 ng/ml. Trough levels must be taken every five to seven days after the initiation of treatment.[5]

The use of Sirolimus for orbital lymphangiomas is still currently limited to results from individual case reports.

Surgery

Surgical debulking and/or excision is another intervention for orbital lymphangioma, however, since the lesions often are adjacent to or intertwine with vital orbital structures, surgery can be a challenge. Additionally, risk of recurrence is high, with a 2015 study showing that of seven patients whom underwent surgical resection of their lesion, recurrence was seen in 71% over an average of 7.2 years.[17] In order to aid with hemostasis and manipulation, surgery can be accompanied with intralesional sclerotherapy or injection of fibrin glue. Fibrin glue can be injected into the lesion causing the mass to solidify, allowing the surgeon to more easily mobilize and excise the mass.[7]

The surgical approaches depend on the location of the lesion, however can include: lateral orbitotomy, a medial upper lid vertical split anterior orbitotomy, a swinging eyelid flap approach, or an upper lid skin crease anterior orbitotomy.[7]

In the most severe cases, where there is posterior orbit involvement, permanent loss of vision, or severe pain, orbital exenteration can be considered.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Forrester MB, Merz RD: Descriptive epidemiology of cystic hygroma: Hawaii, 1986 to 1999. South Med J 97:631-6, 2004

- ↑ Grasso DL, Pelizzo G, Zocconi E, et al: Lymphangiomas of the head and neck in children. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 28:17-20, 2008

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nassiri N, Rootman J, Rootman DB, et al: Orbital lymphaticovenous malformations: Current and future treatments. Surv Ophthalmol 60:383-405, 2015

- ↑ Harris GJ: Orbital vascular malformations: a consensus statement on terminology and its clinical implications. Orbital Society. Am J Ophthalmol 127:453-5, 1999

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Adams DM, Trenor CC, 3rd, Hammill AM, et al: Efficacy and Safety of Sirolimus in the Treatment of Complicated Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics 137:e20153257, 2016

- ↑ Hill RH, 3rd, Shiels WE, 2nd, Foster JA, et al: Percutaneous drainage and ablation as first line therapy for macrocystic and microcystic orbital lymphatic malformations. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 28:119-25, 2012

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Saha K, Leatherbarrow B: Orbital lymphangiomas: a review of management strategies. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 23:433-8, 2012

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Miceli A, Stewart KM: Lymphangioma, StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL), 2019

- ↑ Tunc M, Sadri E, Char DH: Orbital lymphangioma: an analysis of 26 patients. Br J Ophthalmol 83:76-80, 1999

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Raichura ND, Alam MS, Noronha VO, et al: A prospective study of the role of intralesional bleomycin in orbital lymphangioma. J AAPOS 21:146-151, 2017

- ↑ Patel SR, Rosenberg JB, Barmettler A: Interventions for orbital lymphangioma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5:CD013000, 2019

- ↑ Bloom DC, Perkins JA, Manning SC: Management of lymphatic malformations. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 12:500-4, 2004

- ↑ Bagrodia N, Defnet AM, Kandel JJ: Management of lymphatic malformations in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 27:356-63, 2015

- ↑ Barnacle AM, Theodorou M, Maling SJ, et al: Sclerotherapy treatment of orbital lymphatic malformations: a large single-centre experience. Br J Ophthalmol 100:204-8, 2016

- ↑ Gandhi NG, Lin LK, O'Hara M: Sildenafil for pediatric orbital lymphangioma. JAMA Ophthalmol 131:1228-30, 2013

- ↑ Wang S, Zhang J, Ge W, et al: Efficacy and safety of oral sildenafil in treatment of pediatric head and neck lymphatic malformations. Acta Otolaryngol 137:674-678, 2017

- ↑ Russin JJ, Rangel-Castilla L, Kalani MY, et al: Surgical management, outcomes, and recurrence rate of orbital lymphangiomas. J Clin Neurosci 22:877-82, 2015