Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Creuzfeldt-Jakob

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Ophthalmic Manifestations of Creutzfeldt/Jakob disease (CJD); Heidenhain Variant

Disease Entity

Ophthalmic Manifestations of CJD/Heidenhain Variant

Disease

Creutzfeldt Jakob Disease (CJD) is a rare prion (proteinaceous infective particles)-associated neurodegenerative disorder resulting in a spongiform encephalopathy with an estimated incidence of 1 case per 1 million people annually. There are familial, sporadic, and iatrogenic cases of CJD. The Heidenhain variant (HVCJD) is a form of sporadic CJD associated with visual signs and symptoms. Patients with HVCJD have been reported to present with isolated visual symptoms for a duration of anywhere from one to twelve weeks[1]. The HVCJD occurs in 4-20% of CJD cases.[2][3][4] The majority of reports detailing HVCJD are epidemiological studies, reviews, and case reports given the low incidence of disease and lack of controlled clinical studies. This article seeks to provide an overview of ophthalmic manifestations of the HVCJD.

Etiology

Sporadic, familial, iatrogenic, and variant forms of CJD have been recognized as potential culprits.

Risk Factors

Specific risk factors for HVCJD and sporadic CJD in general have not been identified. Common CJD transmission routes include contact with infected animal tissues and iatrogenic spread through contaminated surgical instruments. In ophthalmology, there have been reports of CJD transmission via corneal transplant from previously infected patients.[5] There is a case report of one patient who developed CJD who had received a bovine bioprosthetic aortic valve.[6]

Pathophysiology

The prion PrPSc is believed to be the driving pathological agent in CJD, resulting in recruitment of other cortical proteins and their subsequent misfolding. HVCJD causes posterior cortical degeneration (PCD) and the activity of PrPSc results in neurodegeneration consisting of neuronal loss, gliosis, and spongiform vacuolization of the parietal lobe, occipital lobe, temporal lobe, basal ganglia, and thalami.[4] The types of CJD are classified according to their clinical and molecular basis. Specifically, through examination of the PRNP gene at codon 129. This codon has been found to be homozygous for methionine in several HVCJD cases.[3][4][7]

Diagnosis

History

The CJD Heidenhain variant was first reported by Heidenhain through a report of three patients with a spongiform encephalopathy and cortical blindness in 1929.

Physical examination

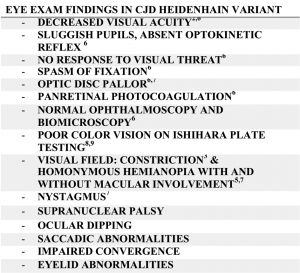

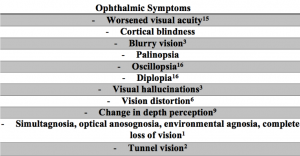

See tables.

Symptoms

Ophthalmic manifestations of HVCJD may occur weeks or months before the onset of other symptoms. A retrospective case series found that in HVCJD cases, isolated visual symptoms most often began with blurred vision and diplopia. As the disease progressed, the incidence of complex visual hallucinations and cortical blindness increased significantly[1].

Non-ophthalmic manifestations of CJD may include occipital headache, myoclonus (startle, spontaneous), cerebellar and pyramidal disease, extra-pyramidal disease, delirium, confusion, disorientation, dystonia, akinetic mutism, aphasia, attention and short memory deficits, abnormal behavior, dysarthria, cognitive decline, ataxia, weakness, clumsiness, ataxic gait, impaired tandem gait, apallic state, rigidity, hypertonicity, athetosis, tremor (intention), dysphonia, dysphagia, dyscalculia, dyschromatopsia, psychosis, ideomotor apraxia, decreased verbal comprehension, decreased arithmetic ability, decreased hand-eye coordination, hemiparesis, positive Babinski, asterixis, depressed DTRs, dysdiadochokinesis, and advanced encephalopathy. [2][3][4][6][7][8][9]

Clinical diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of CJD Heidenhain variant with ophthalmic manifestations is determined by the aforementioned clinical presentation of visual symptoms with other possible neurologic manifestations and is confirmed through evidence of CJD histopathology as to be detailed below.

Diagnostic procedures

The gold standard diagnostic test for CJD Heidenhain variant is molecular and histopathological evaluation (brain biopsy) showing classic findings of CJD such as neuronal loss, gliosis, and spongiform vacuolization of the brain tissue are found in the occipital cortex and sometimes cerebellum. [7][10] Less damage is seen in the basal ganglia, cingulate gyrus, and limbic system compared to non-Heidenhain variant CJD patients overall.[4] Autopsy or brain biopsy with immunostaining for PrPSc is shown in confirmatory testing.[10][9] Tissue samples from suspected cases are often sent to the National Prion Research Center at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland for formal testing. The use of brain biopsy as a confirmatory diagnostic procedure is limited as the use of surgical instrumentation has the potential to transmit CJD to other patients. Although there is a reported case of CJD transmission by tonometry alone, this case is suspect and unproven.[11]

Initial conventional brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be normal initially in HVCJD Over time however up to 80% of patients develop occipitoparietal hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) or fluid-attenuated inversion recover (FLAIR) MRI. [2][4]Additionally, the MRIs of some affected patients may show increased signal in the basal ganglia and temporo-parietal junction.[3][7] Some patients with HVCJD may also show isolated visual cortex atrophy.[4] Despite subtleties in the MRI, visual symptoms may occur due to metabolic inactivity as visualized on single-photon emission computed tomography (PET) has shown reduced perfusion in the parieto-occipital region.[7][8] Electroencephalogram (EEG) of patients with CJD Heidenhain variant has shown normal posterior dominant rhythm, periodic sharp wave complexes (PSWC), 1 Hz spike and wave distribution sometimes bilaterally in the occipital region, periodic triphasic complexes, and diffuse slowing suggestive of encephalopathy.[2][4][6][7][8][12][9] Electroretinography (ERG) has been studied in CJD patients with visual symptoms, revealing potentially a normal ERG or with reduced b waves in cases in which the retina was involved in the disease process.[13] Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has shown temporal atrophy and retinal thinning of the optic nerve in a case with HVCJD.[14]

Laboratory test

In addition to brain biopsy or autopsy to reveal histologic and molecular evidence of CJD, other laboratory measures have shown to be characteristic of this disease. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sampling has shown elevated t-tau and protein 14-3-3, which are indicative of encephalopathy but not specific for CJD especially early in the clinical course, at around 2 weeks, an early indicator as compared to EEG findings which were present at several months into the disease.[2][4] CSF studies have also revealed elevated neuronal specific enolase protein indicative of neuronal degeneration. Western Blot has additionally been used to confirm the presence of PrPSc.[8]Another marker, real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC), has been found to have high sensitivity and specificity.

Differential diagnosis

HVCJD is one of the known causes of PCD therefore other causes of PCD including neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Pick’s disease, and Lewy body dementia must be considered in the differential diagnosis.[3] Additionally, a common pathology that may cause the visual symptoms seen in the HVCJD include an occipital stroke.[3] A diagnosis often attributed with the early visual changes seen in HVCJD patients is cataract, with some patients having received cataract evaluation or surgery after the onset of symptoms but prior to CJD confirmatory diagnosis.[3][12] Other common diagnoses to consider depending on the visual symptoms present in a given case include diabetic ocular motor paresis, epilepsy, and migraine.[7][15] It is important to consider HVCJD variant in patients with visual field loss and normal conventional brain MRI studies.[7]

Management

Unfortunately, there is no proven treatment for CJD and no large controlled clinical studies to evaluate the efficacy of various approaches. The majority of patients only have confirmation of their diagnosis after autopsy and clinicians reluctant to pursue more aggressive confirmatory diagnostic testing due to the risk of surgical contamination and human spread by CJD.[7] Furthermore, given the rapidly progressing nature of CJD, tendency to pursue palliative care options in light of the decline of the individual as most patients expire within several weeks to a few months after symptom onset in an akinetic, mute, and blind state.[7] A case review of 169 CJD patients found that patients with HVCJD had a shorter disease course, 5.7 months, compared to those without 7.5 months.[4] Furthermore, a retrospective case series study found that HVCJD patients with pathogenic PRNP mutations had a significantly longer survival time than those without[1]. Further investigational studies are underway to elucidate new target markers.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Binczyk NM, Smith MJ, Nathoo N, Sim VL, Jeffery D, Jivraj I. Visual Disturbances and Headache as Presenting Symptoms of Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2022 Jun;42(2):e488.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Baiardi S, Capellari S, Ladogana A, et al. Revisiting the Heidenhain Variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: Evidence for Prion Type Variability Influencing Clinical Course and Laboratory Findings. Appleby B, ed. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;50(2):465-476. doi:10.3233/JAD-150668.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Cooper SA, Murray KL, Heath CA, Will RG, Knight RSG. Isolated visual symptoms at onset in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: the clinical phenotype of the “Heidenhain variant.” Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(10):1341-1342. doi:10.1136/bjo.2005.074856.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 Kropp S, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Finkenstaedt M, et al. The Heidenhain Variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(1):55-61. doi:10.1001/archneur.56.1.55.

- ↑ Maddox RA, Belay ED, Curns AT, et al. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in recipients of corneal transplants. Cornea. 2008;27(7):851-854. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31816a628d.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Hashoul J, Saliba W, Bloch I, Jabaly-Habib H. Heidenhain variant of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in a patient who had bovine bioprosthetic valve implantation. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64(10):767. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.195003.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Parker SE, Gujrati M, Pula JH, Zallek SN, Kattah JC. The Heidenhain Variant of Creutzfeldt-jakob Disease—a Case Series. J Neuroophthalmol. 2014;34(1):4-9. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e3182916155.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Prasad S, Lee EB, Woo JH, Alavi A, Galetta SL. MRI and Positron Emission Tomography Findings in Heidenhain Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: J Neuroophthalmol. 2010;30(3):260-262. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e3181e2aef7.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Foundas M, Donaldson MD, McAllister IL, Bridges LR. Vision loss due to coincident ocular and central causes in a patient with Heidenhain variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Age Ageing. 2008;37(2):231-232. doi:10.1093/ageing/afm191.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Jacobs DA, Lesser RL, Mourelatos Z, Galetta SL, Balcer LJ. The Heidenhain variant of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: clinical, pathologic, and neuroimaging findings. J Neuroophthalmol. 2001;21(2):99–102.

- ↑ Eye procedure raises CJD concerns. UPI. https://www.upi.com/Eye-procedure-raises-CJD-concerns/29741100811678/. Accessed October 19, 2017.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Wong A, Matheos K, Danesh–Meyer HV. Visual symptoms in the presentation of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22(10):1688-1689. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2015.05.006.

- ↑ Ishikawa A, Tanikawa A, Shimada Y, Mutoh T, Yamamoto H, Horiguchi M. Electroretinograms in three cases of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with visual disturbances. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2009;53(1):31-34. doi:10.1007/s10384-008-0608-9.

- ↑ Chin EK, Hershewe G, Keltner JL. Rapidly Progressive Homonymous Hemianopia in the Heidenhain Variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2012;36(2):54-58. doi:10.3109/01658107.2012.654925.

- ↑ Cornelius JR, Boes CJ, Ghearing G, Leavitt JA, Kumar N. Visual Symptoms in the Heidenhain Variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. J Neuroimaging. 2009;19(3):283-287. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6569.2008.00294.x.

- Hashimoto M, Obara Y, Yoshida K, Ohguro H. A case of early Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease presenting with acute bilateral visual loss. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2008;52(3):235-235. doi:10.1007/s10384-008-0522-1.

- Lueck CJ, McIlwaine GG, Zeidler M. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and the eye. II. Ophthalmic and neuro-ophthalmic features. Eye. 2000;14(3a):291-301. doi:10.1038/eye.2000.76.