All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Ophthalmia nodosa is an ocular inflammatory condition caused by certain insect hairs or vegetable material, lodging in the conjunctiva, cornea, or iris,[1] and potentially penetrating within the posterior segment.

Disease Entity

Disease

Ophthalmia nodosa is an ocular inflammatory condition precipitated by the embedment and migration of insect hairs, usually caterpillar (CP) setae and seldom tarantula hairs, or vegetable material, [3] into various ocular tissues. Its name derives from the characteristic nodular immunological response that occurs within the conjunctiva, as a reaction to either the mechanical effect and the penetration of the setae or their direct toxic effect. The disease spectrum of ocular pathology is associated with the site and location of the caterpillar hairs, which have a specific property of migrating deep into the tissue with time and causing low-grade chronic inflammation due to releasing of the toxin thaumetopoein.[4][5] Following the entry of the caterpillar setae into the eye, diverse ocular lesions can develop,[6] as ocular involvement may occur in the form of catarrhal conjunctivitis, conjunctival nodules, keratoconjunctivitis, keratitis, iris nodules, uveitis, focal cataract, endophthalmitis, vitritis, pars planitis, papillitis, and chorioretinopathy.[4][6] Ophthalmia nodosa with vitreoretinal involvement due to intraocular penetration of the hairs is rare, but is a potentially disastrous complication,[7] causing vision loss due to persistent inflammation of the eye.[5] Rarely, the damage is severe enough to require enucleation.[8] Therefore, careful removal of all the cilia is essential in order to prevent delayed complications like migration of these cilia in the posterior segment.[4]

A classification of ocular inflammatory reactions caused by the presence of caterpillar setae, as well as released urticating toxins, was developed for Ophthalmia nodosa by Cadera et al.[9][10]

- Type 1 : Acute anaphylactoid toxic reaction to insect hair, which immediately begins with a duration course of a few days, mainly causing chemosis and inflammation.

- Type 2 : Chronic mechanical keratoconjunctivitis caused by hair found in the bulbar or palpebral conjunctiva with foreign body sensation and linear corneal abrasions.

- Type 3 : Formation of grayish-yellow conjunctival granulomas due to subconjunctival or intracorneal setae; patients may remain asymptomatic.

- Type 4 : Iritis secondary to hair penetration into the anterior segment, which may become severe with iris nodule formation and hypopyon.

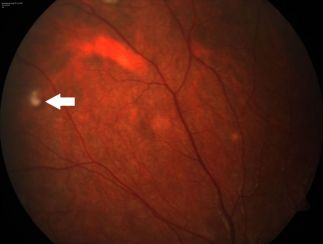

- Type 5 : Early or late vitreoretinal involvement due to penetration of the hair through the cornea, iris, and lens or via the transscleral route; vitritis, cystoid macular edema, papillitis, or endophthalmitis may occur.

Etiology

Caterpillar setae are a well-established cause of Ophthalmia Nodosa due to their tendency to easily migrate intraocularly through the various structures. Caterpillar hairs are sharp and barbed and usually travel base forward, because of the direction of the barbs. The hair is brittle and fracture easily once they have penetrated the eye. They have the ability to travel in the eye, perhaps because of the shape of the hair and stresses from the lid and ocular movements, or even possibly from vascular pulsations.[13]

Light microscopic examination of a nonfixed caterpillar cilia revealed a dark hair shaft with multiple, regularly placed pointed barbs aligned in the same direction protruding at about 30° acute angles. In deeper conjunctival specimen sections, a round, light brown structure with an inner tubule and outer barb-like projections was visualized, consistent with a caterpillar hair.[12] Contact with caterpillar setae can be a result of direct contact with caterpillars, contact with the larval cocoon into which setae may have been shed, and interwoven, or of direct entry of wind-borne setae, whereas the inflammatory reaction caused by the setae are related to their toxicity and locomotion. Toxicity is due to the presence of a foreign body and the effect of released urticating toxins. Toxin originates in the venom gland connected to the hair shaft, which is transferred via the hollow shaft seen in the electron micrographs.[8] A less common cause of Ophthalmia nodosa is tarantula hairs, which resemble sensory setae of caterpillars, both being type III urticating hairs, and are known to migrate relentlessly and cause multiple foci of inflammation in all levels of the eye. Tarantula hairs have been shown to penetrate into the dermal layer of human skin and through Descemet's membrane. Eye rubbing facilitates this process further.[12]

Risk Factors

Ophthalmia nodosa due to caterpillar hair is considered to be a common occupational disease in Eastern Mediterranean-region countries.[9] A certain type of endemic caterpillar species has deleterious harmful effects on the growth and wellbeing of red pine trees, which are highly populated in that region. To avoid colonization of caterpillars on these trees, biological warfare is being waged, with several caterpillar-breeding farms being established in order to feed a particular form of parasite bug on these caterpillars., and after being fed only on these caterpillars, those parasite bugs are released into forestry to get rid of these harmful caterpillars. Although this biological warfare is very popular and successful, particularly in the East Aegean region, ophthalmia nodosa has been recognized as a serious occupational hazard for employees who work in these breeding farms: ophthalmia nodosa, due to lack of wearing protective equipment, inadequate knowledge, and education. [9] Ophthalmia nodosa is also a seasonal disease, due to the preponderance of caterpillars during the months of July–October, more often observed in coastal regions, with the exact incidence of the disease being unknown.[12]

General Pathology

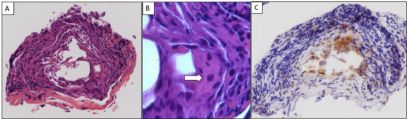

Histopathology of the lesions shows typical granulomatous reaction to a chemical irritant, with the setae being surrounded by lymphoid cells, macrophages, and epithelioid cells surrounded by a thick fibrous capsule, hence the name.[6] Histopathological examination of a conjunctival biopsy specimen disclosed a fragment of inflamed fibrous tissue that contained an occasional multinuclear, foreign-body-type, giant cell (Fig. 2B), with focal infiltrates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages, staining with CD68.[12]

Primary prevention

Prevention of Ophthalmia nodosa can be achieved by wearing protective equipment, as well as providing proper education to high-risk occupational groups, such as workers in caterpillar-feeding parasite breeding farms. Additionally, wearing protective glasses/helmet while commuting on a two-wheeler and playing or working outdoors during caterpillar season.

Diagnosis

History

Patients presenting with clinical features suggestive of ophthalmia nodosa, usually have a history of engaging in outdoor activities, gardening or working in a caterpillar-infested environment. Rarely, patients may mention owing a tarantula pet.

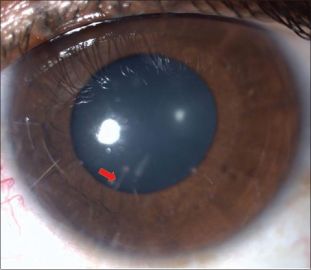

Slit-Lamp examination

Being extremely thin and small, caterpillar setae can be difficult to detect and easily missed on slit-lamp examination. Such missed hairs may remain unnoticed for an extended period of time, causing severe discomfort to the patient in the form of various ocular symptoms.[12] A careful evaluation of the palpebral conjunctiva and fornixes is essential to avoid recurrence of caterpillar cilia in the cornea.[4] Incomplete removal of caterpillar cilia from the eye can be a cause of chronic ocular inflammation. Repeated examinations are required to identify the extent of the disease.[12] In rare cases reported in literature, ophthalmia nodosa may be an incidental finding upon routine ophthalmological examination in patients that exhibit no symptoms or signs.[1] Typical findings in slit-lamp examination include:

Anterior Segment

- Conjunctival chemosis (type I)

- Conjunctival injection (type I)

- Diffuse conjunctival congestion

- Corneal epithelial defects with stromal infiltration (type II)

- Vertical abrasions (patterned abrasions) of corneal epithelium: lid eversion reveals hair as dark spot with surrounding hyperemia near lid margin (type II)

- Conjunctival nodules (type III)

- Ciliary flush

- Anterior chamber inflammation (flare, cells)

- Hypopyon

- Iris nodules

- Visible hair in iris, adjacent trabecular band, or lens (type IV)

Posterior Segment (Type V)

- Setae/hairs in cortical vitreous

- Pars planitis

- Mild-to-moderate vitritis

- Snowballs/snowbanks

- Yellow patches of retinochoroiditis (usually temporal macular area)

- Macular edema

- Papillitis

Symptoms

- ocular pain

- foreign body sensation

- blurry vision

- redness

- discomfort

- lacrimation

- photophobia

- lid edema

- floaters

Diagnostic procedures

Diagnostic imaging modalities that can further aid the diagnosis, management and follow-up of ophthalmia nodosa cases with corneal involvement, include serial anterior segment photography, which involves the assessment of the depth and the extent of pathologic features, and is made possible with the use of :

- Scheimpflug imaging : corneal sites penetrated by caterpillar setae appear high-reflective with irregular stroma and interrupted endothelial surface integrity.[17]

- Anterior Segment OCT imaging (AS-OCT).

- Ultrasound Biomicroscopy (UBM) : setae/hairs appear hyperefective, with or without localized swelling of iris and ciliary body.[18]

Differential diagnosis

- Other asymptomatic nodular conjunctival lesion, such as a dermoid or chalazion.

- Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis (DUSN) [18]

- Penetrating injury by other foreign materials[18]

Management

General treatment

Treatment approach for ophthalmia nodosa depends on the type of the disease. Type I to type III variety generally respond well to removal of the hair and standard topical medications, whereas type IV to V may require more invasive interventions.[7]

Medical therapy

- Type I : Treatment options for the acute anaphylactoid toxic reaction to insect hair include copious irrigation with the use of saline solution, followed by the administration of topical antibiotics and steroids.

- Type 2: Treatment approach is similar to that of Type I, with the addition of removal of all insect setae with the use of forceps, including lid eversion.

Medical follow up

Patients with retained intracorneal hairs should be counseled regarding risk of intraocular penetration and closely followed up for at least six months.[7]

Surgery

- Type 3: removal of conjunctival nodules (to prevent migration to cornea and subsequently other intraocular structures)

- Type 4: topical steroids for keratitis and anterior uveitis; removal of hairs with forceps, iridectomy, and even lensectomy; Nd:YAG laser to disrupt hairs

- Type 5: oral, periocular, or intraocular steroids for inflammatory control (but other infections must be ruled out before ocular injections); Nd:YAG laser to disrupt hairs; vitrectomy for resistant cases .[18]

Surgical follow up

Successful removal of all intracorneal hair significantly reduces the risk of intraocular penetration.[7] However, removing all hair can be very difficult in all instances due to their extreme friability, accompanying corneal edema, surrounding infiltration, and deep lying hair. Most patients have more than one hair, all of which may not be amenable for removal at the first sitting. Thus, patients with retained intracorneal hair must be followed up closely as vision-threatening complications may develop late in the course of the disease.

Complications

Frank endophthalmitis is a rare, sight-threatening complication in cases with posterior segment involvement that occur late in the disease course, even years later. Non-resolving lid edema due to deeply embedded CP hairs, persistent epithelial defect, non-resolving anterior uveitis due to CP hair in the deep stroma and anterior chamber.

Prognosis

Ophthalmia nodosa is a benign disease entity. With timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment, patients usually recover completely within 3 weeks. However, it is often difficult to diagnose, thus it is advisable to maintain a high index of suspicion, especially during the caterpillar season in prevalent areas. Usually, more than one visit is required to remove all the hairs. Repeated examinations are required to identify the extent of the disease.[19]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Prasad SC, Korah S. Rare Presentation of Ophthalmia Nodosa. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22(4):520-521. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.164627

- ↑ Doshi, P. Y., Usgaonkar, U., & Kamat, P. (2016). A Hairy Affair: Ophthalmia nodosa Due to Caterpillar Hairs. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation, 26(1), 136–141. doi:10.1080/09273948.2016.1199708

- ↑ Watson, P G, and D Sevel. “Ophthalmia nodosa.” The British Journal of Ophthalmology vol. 50,4 (1966): 209-17. doi:10.1136/bjo.50.4.209

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Sahay P, Bari A, Maharana PK, Titiyal JS. Missed caterpillar cilia in the eye: cause for ongoing ocular inflammation. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(4):e230275. Published 2019 Apr 15. doi:10.1136/bcr-2019-230275

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Agarwal, Manisha; Acharya, Manisha C1; Majumdar, Shahana2; Paul, Lagan1 Managing multiple caterpillar hair in the eye, Indian Journal of Ophthalmology: March 2017 - Volume 65 - Issue 3 - p 248-250 doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_985_15

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Sridhar, M., Ramakrishnan, M. Ocular lesions caused by caterpillar hairs. Eye 18, 540–543 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700692

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Sengupta, Sabyasachi; Reddy, Padmati Ravindranath; Gyatsho, Jamyang; Ravindran, Ravilla D; Thiruvengadakrishnan, ; Vaidee, Vikram Risk factors for intraocular penetration of caterpillar hair in Ophthalmia Nodosa, Indian Journal of Ophthalmology: Nov–Dec 2010 - Volume 58 - Issue 6 - p 540-543 doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.71711

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Pratik Y. Doshi MS, DNB, FICO, Ugam Usgaonkar MS & Pradnya Kamat MS, FICO (2016): A Hairy Affair: Ophthalmia nodosa Due to Caterpillar Hairs, Ocular Immunology and Inflammation, DOI: 10.1080/09273948.2016.1199708

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Arzu Taskiran Comez, Hasan Ali Tufan & Baran Gencer (2013) Ophthalmia Nodosa as an Occupational Disease: Is It Usual or Is It Casual?, Ocular Immunology and Inflammation, 21:2, 144-147, DOI: 10.3109/09273948.2012.739255

- ↑ Cadera W, Pachtman MA, Fountain JA. Ocular lesions caused by caterpillar hairs (ophthalmia nodosa). Can J Ophthalmol. 1984;19:40–44

- ↑ Prasad SC, Korah S. Rare Presentation of Ophthalmia Nodosa. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22(4):520-521. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.164627

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 Saleh S, Brownstein S, Kapasi M, O'Connor M, Blanco P. Ophthalmia nodosa secondary to caterpillar-hair-induced conjunctivitis in a child. Can J Ophthalmol. 2020 Apr;55(2):e56-e59. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2019.10.001. Epub 2019 Dec 23. PMID: 31879071.

- ↑ Anita Ambastha, Rakhi Kusumesh, Nilesh Mohan, Piyush GuptaMigratory Caterpillar Hairs: A Case Report and Review of Literature.DJO 2018;29:59-60

- ↑ Agarwal, Manisha; Acharya, Manisha C1; Majumdar, Shahana2; Paul, Lagan1 Managing multiple caterpillar hair in the eye, Indian Journal of Ophthalmology: March 2017 - Volume 65 - Issue 3 - p 248-250 doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_985_15

- ↑ Singh R, Tripathy K, Chawla R, Khokhar S. Caterpillar hair in the eye. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017219392. Published 2017 Mar 1. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-219392

- ↑ Jain. N, Kanz Soong. H, Gardner. TW. Ophthalmia Nodosa. Eyenet Magazine. American Academy of Ophthalmology. November 2013.

- ↑ Timucin OB, Baykara M. Role of Scheimpflug imaging in the diagnosis and management of keratitis caused by caterpillar seta. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2010;3(3):150-152. doi:10.4103/0974-620X.71900

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Moses K.N. (2021) Ophthalmia Nodosa. In: Foster C.S., Anesi S.D., Chang P.Y. (eds) Uveitis. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52974-1_59

- ↑ Doshi, P. Y., Usgaonkar, U., & Kamat, P. (2016). A Hairy Affair: Ophthalmia nodosa Due to Caterpillar Hairs. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation, 26(1), 136–141. doi:10.1080/09273948.2016.1199708