Ocular Pentastomiasis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

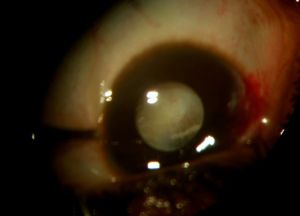

Surgical extraction of an armillifer from the anterior chamber. See the characteristic peristaltic movements of the parasite while it is removed through a clear corneal incision.

Disease Entity

Pentastomiasis is a rare, yet emerging zoonotic disease caused by the larval stage of Pentastomidae. [1]

Etiology

Pentastomidae are a group of parasitic arthropods, also known as tongue worms. They are obligate parasites that inhabit the upper respiratory tract of terrestrial carnivorous vertebrates (mostly reptiles and birds but canids and primates may also be involved).[1][2]

Their phylogenetic classification is still incompletely established but based on sperm morphology and molecular studies, they are currently considered as crustaceans. Along with Branchiura, they form the Ichtyostraca clade. [3][4]

The Pentastomidae subclass is itself divided into two orders:

- Cephalobaeridae, the most primitive

- Porocephalidae, the most evolved

All species known to infect humans are classified as Porocephalidae : [2]

- Linguatula serrata is found in temperate climatic regions

- Porocephalus spp is more prevalent in America;

- Armillifer spp are native from Africa.

Linguatula serrata uses canidae as definitive hosts while both Porocephalus spp and Armillifer spp inhabit snakes as final hosts

Most cases of pentastomiasis reported in humans are due to Armillifer spp infections, in particular A. Armillatus. [5]

Adult worms have a length varying from 1 to 14 cm. Females are generally larger than males. They have five anterior appendages, one of them being the mouth, from which their name is derived (“penta” = mouth and “stoma” = mouth, orifice, in Greek). [3][4]

Pathophysiology

Pentastomidae are obligate parasites. Their adult form is found in the upper respiratory tract of reptiles, birds and even mammals such as dogs or monkeys. There, the male and female worms lay eggs, that are expulsed of the host through the upper airways (cough, saliva, …) or the digestive system (feces). The eggs may then be ingested by an intermediate host, generally a fish or a small rodent, in which larvae hatch, break through the intestinal wall and then form cysts in various body parts. The cycle ends up when the intermediate host is ingested by the main host, in which the worm reaches the upper respiratory tract by crawling from the esophagus.[6]

Humans can be infected by ingesting eggs and become then accidental intermediate hosts, resulting in a parasitic dead-ends as the cycle can’t be completed.

Risk Factors

To give an idea of the magnitude of the threat, a survey conducted in Congo revealed a 87.5 to 92.3 % prevalence of Armillifer spp in various types of snakes sold at bushmeat markets. [7]

- Contact with infected fluids during meals preparation, reuse of washing water [7]

- Illiteracy [7]

- Close contact with the definitive host, in contexts such as totemism, occupational exposure (veterinary medicine, zookeepers, …) or pets keeping. [8][9]

Epidemiology

Due to the asymptomatic nature of the systemic infestation (see the “Diagnosis” chapter) and the lack of access to healthcare in endemic countries, the exact number of patients affected by pentastomiasis is unknown. The few autopsy studies available suggest prevalences ranging from 8% in Cameroon [10] up to 45% in Malaysia [11], as well as 22% in Congo and 33% in Nigeria. [12]

Primary Prevention

The best way to prevent pentastomiasis is to avoid consumption of incriminated meat. However, since livestock is generally rare in the most impacted regions (like Central Africa and South-East Asia), snake, monkey and dog meat are an important source of proteins for the inhabitants and is difficult to renounce to. [7]

Prevention should thus focus on personal hygiene measures when handling possibly infected meat and on a sufficient cooking of the meat. People should also try to bury the bushmeat residues and not leave them accessible to potential intermediate hosts (chicken, dogs, …) that will perpetuate the cycle. [7]

Concerning occupational and domestic exposure, hand hygiene prevails.

Diagnosis

History

Pentastomiasis can be suspected in patients from endemic areas consuming snake or dog meat. In non-endemic areas, immigrants, veterinarians, zookeepers, and pet-snake owners should be considered at risk. [9]

Signs and symptoms

The ingestion of Pentatomidae’s eggs may lead to visceral pentastomiasis, which is generally asymptomatic. However, symptomatic, severe, or even fatal cases have already been reported. The systemic symptoms vary with the location of the parasite and can be very diversified:

- Incidental finding during medical imaging or surgery [13][14]

- Acute abdomen [15][16]

- Jaw osteonecrosis [17]

- Gynecologic complaints [18]

In particular, the ingestion of Linguatula serrata nymphs may lead to nasopharyngeal pentastomiasis, where the human body acts as an aberrant definitive host. This can appear as dysphagia, coughing, sneezing and abnormally frequent vomiting. [19][20]

Ocular involvement is uncommon yet often devastating. It is more likely to be detected as it causes overt signs and symptoms, the most commonly reported being:

- Eye pain

- Conjunctival hyperemia

- Impaired vision or even vision loss [1][21]

- Periorbital edema [22]

- Secondary glaucoma [23]

The symptoms are generally unilateral. Their onset and the final diagnosis may be 4 days up to 36 months apart [1][21], this high variability being mainly explained by a lack of access to healthcare and an insufficient health education and awareness.

Ocular examination

In the eye, larvae of Pentastomidae reside with a decreasing frequency in the anterior chamber, ocular adnexa, or the posterior chamber.[1] A recent case report also suggests an intracapsular location. [21] Depending on their location, they can manifest in different ways and/or induce:

- Subconjunctival mass [22]

- Annulated foreign body, eventually with peristaltic motion, in the anterior chamber [1]

- Cyclitic membrane [1]

- Annulated foreign body, eventually with peristaltic motion, in the lens capsule [21]

- Subretinal annulated, crescent-shaped foreign body [1]

- Retinal detachment [1]

Diagnostic procedures

(Ocular) pentastomiasis is mainly a clinical diagnosis based on the patient's history, complaints, and physical examination. [24]

If pentastomiasis is suspected, abdominal and pulmonary x-rays may be performed to identify cysts, generally appearing as horse-shoe shaped calcifications. [24][25]

Laboratory test

Classically, as in many parasitosis, blood sampling may reveal hypereosinophilia. [24]

But the definite diagnosis requires sampling and molecular identification of the parasite in order to establish its exact nature. [26]

Differential diagnosis

(Ocular) pentastomiasis must be distinguished from other causes of abdominal or pulmonary calcifications and hypereosinophilia, such as: [27]

- Lymphoproliferative disorders

- Cysticercosis

- Tuberculosis

- Malignant tumors

Management

As the vast majority of pentastomiasis infections are asymptomatic, a treatment is rarely indicated. Initiating a treatment in case of asymptomatic infestation (after incidental discovery during imagery for example) is not necessarily recommended as the parasite spontaneously dies after 2 years, and treating at that stage becomes irrelevant. [24]

Medical therapy

There is no standard medical therapy for systemic pentastomiasis. A few articles describe the use of mebendazole as monotherapy [28] or a combination of praziquantel and albendazole or mebendazole [29] [30] in symptomatic cases. Interestingly, two articles mentioned the additional use of traditional Chinese medicine. [28] [29] In all cases, the administration of antiparasitic drugs resulted in clinical and radiological improvement and a dramatic decrease of the number of parasites found in the patient’s feces.

To our knowledge, there are no publications about a potential benefit of antiparasitic drugs in case of ocular pentastomiasis.

Surgery

Surgery is restricted to symptomatic pentastomiasis, especially in severe presentations or for patients at risk of a negative outcome.

Exploratory laparotomy in patients suffering from acute abdominal symptoms allows not only the diagnosis of pentastomiasis but also an improvement of the patient’s condition. A peritoneal lavage may be performed at the end of the procedure. [24][28]

Surgical extraction is the preferred treatment in case of ocular involvement, an early removal of the parasite being a factor of better prognosis, as it minimizes the exposure of the eye to inflammatory reactions and mechanical alterations related to the presence of larvae.[1] Nymphs can be removed through corneoscleral/limbal incisions, vitrectomy, iridectomy or lens extraction. [1][21]

Complications

Intraocular pentastoma nymphs can induce dramatic intraocular inflammation and mechanical damage resulting in corneal decompensation, lens melting or retinal detachment. These can ultimately lead to blindness.

Prognosis

The prognosis of ocular pentastomiasis depends on the time needed to make the diagnosis, on the evolutionary stadium of the larvae and on its location in the eye with a permanent decrease of visual acuity in 69% and a total visual loss in 31% of reported cases. [1]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Sulyok M, Rózsa L, Bodó I, Tappe D, Hardi R. Ocular pentastomiasis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Plos Negl Trop Dis. 2014 Jul 24;8(7):e3041. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003041

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Koehsler M, Walochnik J, Georgopoulos M, Pruente C, Boeckeler W, Auer H, Barisani-Asenbauer T. Linguatula serrata tongue worm in human eye, Austria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 May;17(5):870-2. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.100790.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lavrov DV, Brown WM, Boore JL. Phylogenetic position of the Pentastomida and (pan)crustacean relationships. Proc Biol Sci. 2004 Mar 7;271(1538):537-44. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2631.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Møller OS, Olesen J, Avenant-Oldewage A, Thomsen PF, Glenner H. First maxillae suction discs in Branchiura (Crustacea): development and evolution in light of the first molecular phylogeny of Branchiura, Pentastomida, and other "Maxillopoda". Arthropod Struct Dev. 2008 Jul;37(4):333-46. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2007.12.002

- ↑ Ioannou P, Vamvoukaki R. Armillifer Infections in Humans: A Systematic Review. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019 May 16;4(2):80. Doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed4020080.

- ↑ Tappe D, Dijkmans AC, Brienen EA, Dijkmans BA, Ruhe IM, Netten MC, van Lieshout L. Imported Armillifer pentastomiasis: report of a symptomatic infection in The Netherlands and mini-review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014 Mar-Apr;12(2):129-33. Doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.10.011

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Hardi, R., Babocsay, G., Tappe, D. et al. Armillifer-Infected Snakes Sold at Congolese Bushmeat Markets Represent an Emerging Zoonotic Threat. EcoHealth 14, 743–749 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-017-1274-5

- ↑ Dakubo J, Naaeder S, Kumodji R. Totemism and the transmission of human pentastomiasis. Ghana Med J. 2008 Dec;42(4):165-8. PMID: 19452026; PMCID: PMC2673832.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mendoza-Roldan JA, Modry D, Otranto D. Zoonotic Parasites of Reptiles: A Crawling Threat. Trends Parasitol. 2020 Aug;36(8):677-687. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2020.04.014.

- ↑ Palmer Philip ES, Reeder MM. The imaging of tropical diseases with epidemiological, pathological and clinical correlations, 2. Berlin: Springler; 2001. p. 389–95

- ↑ Prathap K, Lau KS, Bolton JM. Pentastomiasis: a common finding at autopsy among Malaysian aborigines. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1969 Jan;18(1):20-7.

- ↑ Smith JA, Oladiran B, Lagundoye SB (1975) Pentastomiasis and malignancy. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 69: 503–512

- ↑ Flood R, Karteszi H. Incidental thoracic, hepatic and peritoneal calcifications: a case of Pentastomiasis. BJR Case Rep. 2018 Aug 2;5(1):20180058. doi: 10.1259/bjrcr.20180058.

- ↑ Potters I, Desaive C, Van Den Broucke S, Van Esbroeck M, Lynen L. Unexpected Infection with Armillifer Parasites. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 Dec;23(12):2116-2118. doi: 10.3201/eid2312.171189.

- ↑ Asemota J, Talbet J, Igbinosa O, Igbinovia O. Disseminated Armillifer armillatus Infestation: A Rare Cause of Acute Abdomen. Cureus. 2021 May 15;13(5):e15038. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15038.

- ↑ Lai C, Wang XQ, Lin L, Gao DC, Zhang HX, Zhang YY, Zhou YB. Imaging features of pediatric pentastomiasis infection: a case report. Korean J Radiol. 2010 Jul-Aug;11(4):480-4. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2010.11.4.480

- ↑ Cho ES, Jung SW, Jung HD, Lee IY, Yong TS, Jeong SJ, Kim HS. A Case of Pentastomiasis at the Left Maxilla Bone in a Patient with Thyroid Cancer. Korean J Parasitol. 2017 Aug;55(4):433-437. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2017.55.4.433

- ↑ Tappe D, Dijkmans AC, Brienen EA, Dijkmans BA, Ruhe IM, Netten MC, van Lieshout L. Imported Armillifer pentastomiasis: report of a symptomatic infection in The Netherlands and mini-review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014 Mar-Apr;12(2):129-33. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.10.011

- ↑ Ma KC, Qiu MH, Rong YL. Pathological differentiation of suspected cases of pentastomiasis in China. Trop Med Int Health. 2002 Feb;7(2):166-77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00839.x.

- ↑ Tabaripour R, Keighobadi M, Sharifpour A, Azadeh H, Shokri A, Banimostafavi ES, Fakhar M, Abedi S. Global status of neglected human Linguatula infection: a systematic review of published case reports. Parasitol Res. 2021 Sep;120(9):3045-3050. doi: 10.1007/s00436-021-07272-y

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Koulalis J, Mayala T, Koller J, Hardi R, Dugauquier A. Wriggling surprise during cataract surgery. Submitted.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Reid AM, Jones DW. Porocephalus armillatus larvae presenting in the eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1963 Mar;47(3):169-72. doi: 10.1136/bjo.47.3.169.

- ↑ Lang Y, Garzozi H, Epstein Z, Barkay S, Gold D, Lengy J. Intraocular pentastomiasis causing unilateral glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987 May;71(5):391-5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.5.391.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Tappe D, Büttner DW. Diagnosis of human visceral pentastomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3(2):e320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000320.

- ↑ Mapp Esmond M, Pollack Howard M, Goldman Louis H. Roentgen diagnosis of Armillifer armillatus infestation (Porocephalosis) in man. J Natl Med Assoc 1976:198–200.

- ↑ Tappe D, Sulyok M, Rózsa L, Muntau B, Haeupler A, Bodó I, Hardi R. Molecular Diagnosis of Abdominal Armillifer grandis Pentastomiasis in the Democratic Republic of Congo. J Clin Microbiol. 2015 Jul;53(7):2362-4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00336-15.

- ↑ Vanhecke C, Le-Gall P, Le Breton M, Malvy D. Human pentastomiasis in Sub-Saharan Africa. Med Mal Infect. 2016 Sep;46(6):269-75. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2016.02.006.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Yao MH, Wu F, Tang LF. Human pentastomiasis in China: case report and literature review. J Parasitol. 2008 Dec;94(6):1295-8. doi: 10.1645/GE-1597.1.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Ye F, Sheng ZK, Li JJ, Sheng JF. Severe pentastomiasis in children: a report of 2 cases. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2013 Jan;44(1):25-30

- ↑ Wang HY, Zhu GH, Luo SS, Jiang KW. Childhood pentastomiasis: a report of three cases with the following-up data. Parasitol Int. 2013 Jun;62(3):289-92. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2013.02.007.