Ocular Ortner Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Ocular Ortner syndrome (OOS) is an uncommon but characteristic combination of hoarseness (from recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement) and visual loss due to large vessel involvement (e.g., aortitis) in vasculitides including giant cell arteritis and in Takayasu arteritis. Imaging of the chest (including the great vessels) may be necessary to make the diagnosis. Prompt treatment of vasculitis in OOS with corticosteroids is recommended to prevent potentially blinding complications of ocular ischemia.

Source: YouTube. Ortner’s Syndrome and Rowland-Payne Syndrome. https://youtu.be/xoKO1K5UQis Accessed August 30, 2023.

Disease Entity

Disease

Vocal hoarseness resulting from a cardiovascular disease process compressing the recurrent laryngeal nerve is known as Ortner’s syndrome (OS). Ocular Ortner Syndrome (OOS) is a rare condition characterized by hoarseness with concomitant vision loss which is typically the result of underlying large vessel vasculitis.

History

Ortner syndrome was first described by Ortner in 1897 who reported on the development of vocal paralysis from left recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy in patients with left atrial enlargement due to mitral stenosis.[1] The definition of OS has since evolved to include any cardiovascular condition leading to compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve.[2]

Vision loss can be associated with OS. OOS was first reported by Ali and Figueiredo (2005) in a patient with hoarseness and vision loss due to giant cell arteritis (GCA).[3] The patient had a swollen right optic disc consistent with anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) and elevated serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein levels (CRP). A temporal artery biopsy confirmed GCA and the hoarseness resolved following treatment with high-dose steroids.

Edrees (2012) described another case of OS as the initial presentation of GCA[2] sudden onset of dysphagia and hoarseness. Two weeks later, the patient developed a headache with associated blurry vision in her left eye which improved upon administration of high-dose corticosteroids. Chest X-ray demonstrated unfolding of the aortic arch and a chest CT scan showed diffuse thickening and dilation of the wall of the thoracic aorta, suggestive of inflammatory process. A right temporal biopsy showed GCA and the patient had resolution of the hoarseness after steroids.

Pathogenesis

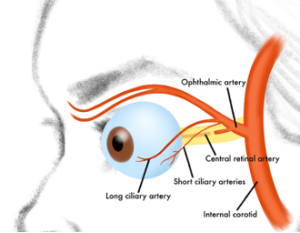

OOS typically develops when inflammatory cardiovascular processes, typically in the form of aortitis, leads to hoarseness due to compression of recurrent laryngeal nerves and vision loss through secondary involvement of the ophthalmic artery or its branches.[3][4] Large vessel vasculitis (e.g., GCA in the elderly or Takayasu arteritis in younger adults), for example, can produce OOS.

Hoarseness in OOS is thought to be the result of ischemic damage to branches of the external carotid arteries supplying laryngeal muscles or the result of chronic, thickening and fibrosis of the vessel walls from aortitis causing compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve which supplies the intrinsic muscles of the larynx except for the cricothyroid muscle.[4][5] Vessel enlargement due to proliferation of immune cells in the media and adventitia, mainly lymphocytes and macrophages produces the aortitis.[5]

The proximity of the right recurrent laryngeal nerve and the left recurrent laryngeal nerves to the right subclavian artery and aortic arch, respectively, renders them vulnerable to injury from the aforementioned cardiovascular processes. Progressive inflammation of these vessels can result in involvement of the common carotid and internal carotid arteries, leading to lumen narrowing. Concomitant vision loss in OOS is, therefore, the consequence of reduced perfusion to downstream retinal vessels (e.g., ophthalmic artery or central retinal artery occlusion, AION, or ocular ischemic syndrome). [6][7]

Epidemiology

Given the few accounts of OOS in the literature, epidemiological data is largely ill defined.

Diagnosis

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with OOS may present with acute respiratory tract symptoms (e.g., hoarseness or dysphonia, cough, or throat pain) and visual changes from ischemia.[2][3][4][8] Constitutional symptoms may also occur (e.g., headache, fatigue, and fever). OOS can be the presenting finding of large vessel vasculitis and a comprehensive history should be obtained from such patients screening for other symptoms of vasculitis (e.g., GCA) including temporal tenderness, jaw claudication, limb claudication, angina pectoris, asymmetric pulse malaise, myalgia, arthralgia, etc.). [2][3]

Physical Exam

A complete eye exam should be performed in any patient suspected of having OOS. Measurement of the visual acuity and visual field, the pupil responses including a relative afferent pupillary defect, and evaluation of the extraocular motility, slit lamp biomicroscopy, and fundus examination are recommended.

Diagnostic Procedures

Serum acute phase reactants and inflammatory markers (e.g. ESR, CRP) may be helpful when concerned for underlying vasculitides.

Imaging of the aorta and its branches with CT or MR or ultrasound may be useful to detect radiographic signs of vasculitis. If GCA is suspected, duplex ultrasound of the temporal, extracranial, and cranial arteries can be performed, though the use of temporal artery biopsy continues to be the gold standard.[9] Diagnosis is confirmed by clinical suspicion in combination with visualization of vascular wall thickening and luminal narrowing on ultrasound, MR angiography, and/or CT angiography. [10]

Fundus fluorescein angiography may help to identify choroidal ischemia and choroidal filling defects in GCA. [11]

Management

General Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment of vasculitic OOS includes immediate therapy with high-dose corticosteroids. Steroids may result in rapid symptom resolution and reduce the risk of subsequent permanent ocular complications. In cases suspicious for large vessel vasculitis, intravenous or high dose oral glucocorticoids (e.g., prednisone 40–60 mg) may be utilized once daily followed by gradual tapering over 2-4 weeks to a maintenance dose.[12]

References

- ↑ Ortner N. Recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis with mitral stenosis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1897;10:753–755.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Edrees, A. (2012). Ortner’s syndrome as a presenting feature of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology international, 32, 4035-4036.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Ali, M. N., & Figueiredo, F. C. (2005). Hoarse voice and visual loss. The British journal of ophthalmology, 89(2), 240. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2004.047860

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Larson, T. S. (1984). Respiratory Tract Symptoms as a Clue to Giant Cell Arteritis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 101(5), 594. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-101-5-594

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Gravanis, M. B. (2000). Giant cell arteritis and Takayasu aortitis: morphologic, pathogenetic and etiologic factors. International journal of cardiology, 75, S21-S33.

- ↑ Hayreh, S. S., Podhajsky, P. A., & Zimmerman, B. (1998). Ocular manifestations of giant cell arteritis. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 125(4), 509–520. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80192-5

- ↑ Mizener, J. B., Podhajsky, P., & Hayreh, S. S. (1997). Ocular ischemic syndrome. Ophthalmology, 104(5), 859-864.

- ↑ Ling, J. D., Hashemi, N., & Lee, A. G. (2012). Throat pain as a presenting symptom of giant cell arteritis. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology, 32(4), 384.

- ↑ Schmidt, W. A. (2018). Ultrasound in the diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology, 57(suppl_2), ii22-ii31.

- ↑ Maz, M., Chung, S. A., Abril, A., Langford, C. A., Gorelik, M., Guyatt, G., ... & Mustafa, R. A. (2021). 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation guideline for the management of giant cell arteritis and Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Care & Research, 73(8), 1071-1087.

- ↑ Von Blotzheim, S. G., & Borruat, F. X. (1997). Neuro-ophthalmic complications of biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis. European journal of ophthalmology, 7(4), 375-382.

- ↑ Buttgereit, F., Dejaco, C., Matteson, E. L., & Dasgupta, B. (2016). Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis: a systematic review. Jama, 315(22), 2442-2458.