Ocular Manifestations of Wyburn-Mason Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Wyburn-Mason Syndrome (also known as Bonnet-Bechaume-Blanc syndrome, Congenital Unilateral Retinocephalic Vascular Malformation Syndrome, Racemose Angiomatosis). ICD 10: Q28.2.

Disease

Wyburn- Mason Syndrome is an exceedingly rare, non-hereditary congenital neurocutaneous disorder leading to arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). Infants affected with Wyburn-Mason syndrome present with arteries that directly connect to veins without capillaries and lead to a fragile mass of abnormal blood vessels found in the midbrain, eyes, orbit and rare cutaneous nevi. Wyburn- Mason syndrome is often included in the phakomatoses syndromes, which cause tumors or masses in the brain, spinal cord and other organs. [1]

Etiology

The exact etiology of Wyburn-Mason syndrome is currently unknown. No specific genetic or hereditary pattern has been identified. It is hypothesized that it is caused by a sporadic abnormality in the development of blood vessels during embryonic or fetal growth.[2] However, the exact mechanism that causes the vascular malformations is not known. [1]

Risk Factors

Wyburn-Mason Syndrome is a very rare disease. The incidence and prevalence rates of this syndrome are currently unknown.[1] The disease does not have any racial or gender predilection, and females and males are affected equally.[2]

General Pathology

Wyburn-Mason Syndrome presents with multiple AVMs of the brain, orbit, retina, and skin. In the retina, the AVMs can affect the entire retina (29.8%) or be located more focally in one or more quadrants of the retina (70.2%). [3] Orbital AVMs can occur in 61.5%. [3]

Pathophysiology

Wyburn-Mason Syndrome is characterized by the presence of AVMs that vary in size and location. These lesions are direct artery-to-vein communications without a capillary system in between to mitigate the high-flow arterial blood. The resulting turbulence in the vessel can cause vessel wall damage, which may result in thrombosis and occlusion. Obstruction of the vessels can lead to ischemia downstream of the occlusion.

Histological analysis of AVMs can reveal an irregularly thick muscularis layer of the arterial and venous walls with or without stromal hemorrhage.

The extent of AVMs in target organs are associated with clinical symptoms. Lesions in the eye or orbit are almost always unilateral and can lead to vision loss. [4] This can be due to the AVMs obscuring visual fields, choroidal infarctions, vascular occlusions, optic disc edema or optic disc atrophy. [3]

In the retina, AVMs tend to grow slowly, but pregnancy, menarche, and trauma can accelerate growth. [5] Retinal AVMs are associated with vascular occlusions that can lead to visual loss. Vein occlusions can be complicated by additional pathologies such as rubeosis iridis, retinal neovascularization, and neovascular glaucoma. [3] These complications may be related to progressive ischemia postulated to be from thromboses, venous compression from the AVM, or a steal phenomenon where blood is diverted from some areas of the retina. [6][7]Although less common, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment as a complication of AVMs have been reported. [8] Retinal hemorrhage and retinal vein occlusions are two of the most frequently occurring ocular complications of this syndrome. [9]

Retinal AVMs can also cause intraretinal edema not associated with a vascular occlusion. The exact mechanism of the macular edema is debated. It was previously suggested that the probable leakage sites are either the capillaries that are adjacent to the malformation or from the anastomosing vessels. The venous shunt vessels are not able to withstand the high intraluminal pressure arising from the arteries without a mitigating capillary system. This elevated venous pressure causes a backpressure in the capillaries surrounding the malformation and these capillaries start to leak. [10] In theory, a steal phenomenon with subsequent retinal ischemia might lead to upregulation of the permeability factor, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Anti-VEGF injected into the vitreous has been reported as treatment for macular edema, but the exact mechanism of how anti-VEGF reduces macular edema is unknown. It is also hypothesized to decrease vascular permeability and increase tight junction proteins, thereby decreasing the leakiness of vessels. [11]

The nervous system manifestation of Wyburn-Mason syndrome most commonly involves the orbit, followed by the midbrain region, the thalamus, hypothalamus, optic chasm, and suprasellar region[12]. However, AVMs have also been reported in the maxilla, pterygoid fossa, mandible, baso-frontal region, and posterior fossa. High vascular flow rate and volume of blood in these vessels can diminish the elasticity of the walls leading to sclerotic vasculature and a higher predisposition to aneurysms. [5] Spontaneous hemorrhage of intracranial lesions are a concern and therefore proper head imaging is required if AVMs are seen in the retina.

AVMs in the cortex can have visual manifestations. If present in the occipital lobe, visual symptoms and headaches may occur. The visual symptoms are typically brief and transient. Hemispheric AVMs can cause homonymous visual field defects. Although rare, visual auras such as scintillating scotoma can occur as they do with migraines. These intracranial malformations may result in steal phenomenon, where shunting of blood to the malformation results in diminished blood flow to the surrounding arteries and brain tissue. Diminished blood flow to cerebral visual territories can present as transient vision loss. [5] [8]

Primary Prevention

There is no recommended prevention for Wyburn-Mason syndrome. Furthermore, there are no known genetic causes or risk factors associated with the disease.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Wyburn-Mason syndrome is made with a thorough clinical exam. Dilated funduscopic exam can reveal the typical appearance of arteriovenous malformations of the retina. Brain MRI can determine the presence and extent intracranial AVMs. The diagnosis of the syndrome is usually delayed until late childhood because of the rarity of cutaneous manifestations.

To diagnose Wyburn-Mason, Group 3 AVMs with concomitant intracranial AVMs must be present to diagnose the syndrome. Severity and characteristics of AVMs were divided into three groups by Archer et al. [13]

Group 1: Defined as a retinal arteriovenous malformation containing a major artery and vein with an abnormal capillary plexus in between. These lesions typically remain asymptomatic.

Group 2: Defined as a retinal arteriovenous malformation between an artery and a vein without any capillary network in between. These have a risk of retinal complications.

Group 3: Defined as complex and extensive AVM’s with large vessels without a capillary plexus in between. These have a high risk for retinal complications and more likely to have intracranial malformations.

History

The constellation of AVMs of the retina and brain with facial vascular changes was first described in 1932. [14] [15] In 1937, Bonnet, Dechaum and Blanc published two additional patients with these findings. [16] In 1943, R. Wyburn-Mason described nine clinical histories with this syndrome. [17] In the literature, the syndrome is commonly referred to Bonnet-Dechaum-Blanc syndrome or Wyburn-Mason syndrome.

Physical Examination

The visual acuity of patients with AVMs of the retina could be normal to mildly reduced when AVMs occur locally in contrast to more extensive AVMs causing significantly reduced vision. Visual field abnormalities including a homonymous hemianopia may suggest presence of cerebral AVMs.

Orbital AVMs are common and can present as unilateral proptosis. Unilateral proptosis can also present in people with intracranial AVMs without orbital involvement. Orbital ultrasound should be considered for those with suspicion of orbital AVM. Ocular motility abnormalities including nystagmus or strabismus may also be a sign for orbital involvement in Wyburn-Mason syndrome.

Dilated funduscopic examination reveals retinal AVMs, which can be present diffusely or more commonly as localized lesions in one or more quadrants of the retina. Complications of AVMs including retinal hemorrhages, vitreous hemorrhage and macular edema may be seen on examination. Optic atrophy may also be present.

Even though Wyburn-Mason is classified as one of the phakomatoses, skin manifestations are not as commonly seen as with other phakomatoses. If present, neurocutaneous nevi can be found on the face. Rarely vessels can be found on the skin of the face or lips. [18]

Signs and Symptoms

Significant heterogeneity exists in the presentation of Wyburn-Mason Syndrome and depends on the number, location, and type of arteriovenous malformations present. Despite being present at birth, infants may or may not present with symptoms in the eyes, central nervous system, orbit and the skin. Some cases have described symptoms in the second or third decade of life. Small AVMs may be asymptomatic whereas larger AVMs may cause significant vision loss due to retinal ischemia. If AVMs are diagnosed at an early age, there is a higher risk of systemic involvement.

Ocular signs or symptoms

- Proptosis

- Blepharoptosis

- Abnormally dilated vessels of the conjunctiva

- Nerve palsies

- Nystagmus

- Strabismus

- Decreased visual acuity or total blindness (retinal ischemia, intraocular lesions)

- Vitreous Hemorrhage

- Vein occlusions

- Retinal Detachment

- Secondary Glaucoma (Neovascular Glaucoma)

- Rubeosis Iridis

- Optic Disc Edema

- Optic Atrophy

Neurological Symptoms

- Severe Headaches

- Vomiting

- Seizures

- Paralysis (from Cranial nerves)

- Nuchal Rigidity

- Epistaxis

- Hemorrhaging

- Hydrocephalus

- Hemiparesis, Hemiplegia or Death

Cutaneous and other Organ system Signs

- Facial Angiomas

- Oral Hemorrhage (Excessive Bleeding with dental procedures)

- Hematuria

- Hemoptysis

Diagnostic procedures

Dilated Funduscopic Exam: reveal unilateral tortuous dilated retinal vessels

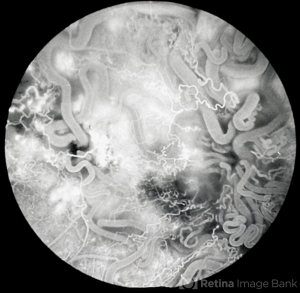

Fluorescein angiography: demonstrates rapid filling of vascular anomalies without significant leakage (Figure 2) [19]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging: indicates the location, size, mass effect, edema of intracranial arteriovenous malformations

Cerebral angiography: displays the characteristics of feeding arteries and draining veins, indicates the exact architecture of the anomaly

Optical Coherence Tomography: enlarged thickened retinal vessels and retinal edema, when present, can be visualized [2]

Differential diagnosis

- Sturge-Weber Syndrome

- Von Hippel- Lindau Disease

- Rendu-Osler-Weber Disease (Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasis)

- Capillary Retinal Hemangiomas

- Familial Retinal Arteriolar Tortuosity

Management

Medical Management

Traditionally, a patient with Wyburn-Mason Syndrome is followed by a cohort of physicians (ophthalmology, primary care, radiology, neurology and/or neurosurgery, and hematology), in addition to a social worker. The majority of retinal AVM cases are stable. [1] Treatment is reserved for patients who are visually compromised and for those who experience discomfort because of the symptoms. Management of Wyburn-Mason syndrome is conservative although surgical options are available. Patients with retinal AVMs are recommended to have brain imaging to rule out intracranial AVMs. Regular ophthalmologic evaluations are required to monitor AVMs and their potential complications.

Surgical Management

Certain brain AVMs, depending on location, can be surgically resected. For AVMs that are not amenable to surgery, alternative measures, such as embolization and radiation therapy, may be considered. [20] Radiation therapy, such as Linac, Gamma knife, Cyberknife, and embolization, which is a catheter technique that delivers an occlusive substance to the abnormal vessel can be considered. Embolization of AVMs is performed by neuroradiologists or neurosurgeons. [21]

Complications of retinal AVMs including neovascularization of the retina into the vitreous or neovascular glaucoma from retinal vein occlusions can be treated with panretinal photocoagulation, and consideration of anti-angiogenic agents. Macular edema secondary to vein occlusions can also be treated with intravitreal anti-VEGF agents. [22] Pars plana vitrectomy can be considered for massive vitreous hemorrhage that does not clear after a few weeks. Another indication for pars plana vitrectomy includes traction retinal detachments. [23]

Complications

Retinal AVMs can be complicated by retinal hemorrhages (28.1%), retinal vein occlusions (17.5%), vitreous hemorrhage (10%), and secondary glaucoma (secondary to neovascularization or elevated episcleral venous pressure). [3] Retinal ischemia resulting in neovascular glaucoma is associated with a poor prognosis. Mechanical compression of the optic nerve can occur and lead to gradual or complete blindness. Retinal edema and detachments have also been reported. [18]

Prognosis

Patients with Wyburn- Mason syndrome may remain asymptomatic; however, some patients have significantly decreased vision or total blindness due to late ocular complications, particularly ischemic complications. [9] Long-term results indicate that the recurrence rate for extracranial AVMs after surgical resection is 81% and 98% with embolization. [24] Of note, this condition is associated with high morbidity and mortality due to the high risk of spontaneous cerebral AVM hemorrhage. [2] The AVMs in the retina can remain stable over several years. Spontaneous resolution has been reported, but it is rare. Because of ocular complications of AVMs, including ischemic vascular occlusions, patients will need to be regularly monitored. [3]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Kaplan, Henry J. “Wyburn Mason Syndrome.” Retina Image Bank, 2013, imagebank.asrs.org/file/6211/wyburn-mason-syndrome.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 So JM, Holman RE. Wyburn-Mason Syndrome. [Updated 2020 Feb 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Schmidt D, Pache M, Schumacher M. The congenital unilateral retinocephalic vascular malformation syndrome (Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome or Wyburn-Mason syndrome): review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:227-49.

- ↑ Liu W, Sharma S. Ophthaproblem. Retinal arteriovenous malformations (type 2). Can Fam Physician. 2005;51(2):203–209.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Neil R., et al. Walsh and Hoyt's Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. Williams & Wilkins, 1998.

- ↑ Rao P, Thomas BJ, Yonekawa Y, Robinson J, Capone A, Jr. Peripheral retinal ischemia, neovascularization, and choroidal infarction in wyburn-mason syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015;133:852-54.

- ↑ Fortes B, Lin J, Prakhunhungsit S, Mendoza-Santiesteban C, Berrocal AM. Spectrum of peripheral retinal ischemia in Wyburn-Mason syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2020;18:100640.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Medina, Flávio Maccord, et al. “Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment in Wyburn-Mason Syndrome: Case Report.” Arquivos Brasileiros De Oftalmologia, vol. 73, no. 1, 2010, pp. 88–91., doi:10.1590/s0004-27492010000100017.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Qin XJ, Huang C, Lai K. Retinal vein occlusion in retinal racemose hemangioma: a case report and literature review of ocular complications in this rare retinal vascular disorder. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14:101. Published 2014 Aug 21. doi:10.1186/1471-2415-14-101

- ↑ Kohli, Piyush, et al. “Wyburn–Mason Syndrome Presenting with Bilateral Retinal Racemose Hemangioma with Unilateral Serous Retinal Detachment.” Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, vol. 66, no. 12, 2018, p. 1869., doi:10.4103/ijo.ijo_455_18.

- ↑ Winter, Eva, et al. “Anti-VEGF Treating Macular Oedema Caused by Retinal Arteriovenous Malformation - a Case Report.” Acta Ophthalmologica, vol. 92, no. 2, 2012, pp. 192–193., doi:10.1111/aos.12019.

- ↑ Samara A, Gusman M, Aker L, Parsons MS, Mian AY, Eldaya RW. The Forgotten Phacomatoses: A Neuroimaging Review of Rare Neurocutaneous Disorders. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2022 Sep-Oct;51(5):747-758. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2021.07.002. Epub 2021 Aug 28. PMID: 34607749.

- ↑ Archer DB, Deutman A, Ernest JT, Krill AE. Arteriovenous communications of the retina. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;75:224-41.

- ↑ S. Brock, C.G. Dyke Venous and arterio-venous angiomas of the brain. A clinical and roentgenographic study of eight cases (case 3) Bull Neurol Inst New York, 2 (1932), pp. 257-265

- ↑ E.F. Krug, B. Samuels Venous angioma of the retina, optic nerve, chiasm and brain. A case report with postmortem observations Arch Ophthalmol, 8 (1932), pp. 871-879

- ↑ P. Bonnet, J. Dechaume, E. Blanc L'anévrysme cirsoïde de la face et avec l'anévrysme cirsoïde du cerveau J Méd Lyon, 18 (1937), pp. 165-178

- ↑ R. Wyburn-MasonArteriovenous aneurysm of mid-brain and retina, facial naevi and mental changes Brain, 66 (1943), pp. 163-202

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 Turell ME, Singh AD. Vascular tumors of the retina and choroid: diagnosis and treatment. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2010;17(3):191–200.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 Hunyor, Alex. “Retinal AV Malformation FA 4.” Retina Image Bank, 2013, imagebank.asrs.org/file/3237/retinal-av-malformation-fa-4.

- ↑ Warrier S, Prabhakaran VC, Valenzuela A, Sullivan TJ, Davis G, Selva D. Orbital Arteriovenous Malformations. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(12):1669–1675. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.501

- ↑ Ellis, J. A., & Lavine, S. D. (2014). Role of embolization for cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Methodist DeBakey cardiovascular journal, 10(4), 234–239. https://doi.org/10.14797/mdcj-10-4-234

- ↑ Callahan AB, Skondra D, Krzystolik M, Yonekawa Y, Eliott D. Wyburn-Mason Syndrome Associated With Cutaneous Reactive Angiomatosis and Central Retinal Vein Occlusion. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46(7):760‐762.

- ↑ Karel I. Indikace pars plana vitrektomie [Indications for pars plana vitrectomy]. Cesk Oftalmol. 1989;45(2):65–70.

- ↑ Link T, Kam Y, Ajlan R. Ocular infarction following ethanol sclerotherapy of an arteriovenous malformation. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2019;15:100457. Published 2019 Apr 25. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2019.100457