Ocular Manifestations of Ectodermal Dysplasia

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Original contributors: Srijith Kambala, Stephanie Trejo Corona, Sarah Rashdan, Minh Nguyen, Jay Jaber, Michael T Yen, MD

Disease Entity

Ectodermal dysplasia (ED) refers to a group of over 180 genetic syndromes linked with abnormal development of the ectodermal structures including hair, teeth, nails, and sweat glands. Additional structures include the central nervous system, cochlea, retina, cornea, conjunctiva, and lacrimal apparatus 1. These gene mutation disorders involve cell signaling pathways of ectodermal organ induction, development, and homeostasis. There are two classifications of ED-related disorders:

Pure ectodermal dysplasias are disorders that present only with signs of defects in ectodermal organs. ‘‘Syndromes of ectodermal dysplasia and malformation” have ectodermal signs and defects in organs of another embryonic origin, commonly cleft palate or lip.

Etiology

Previously, subtypes of ectodermal dysplasia had been classified based on the involvement of hair, teeth, nails, and sweat glands, in a system known as 1-2-3-4 method created by Freire‑Maia where disorders were grouped by their involvement of these key four ectodermal structures 2. Recently, there has been a push to reclassify types of ED, as more research has been conducted on the signaling pathways involved in the condition. A new classification described by Wright et al. groups these disorders broadly into defects of the ectodysplasin A (EDA)/nuclear factor kappa B (NFKB) pathway, wingless related integration site (WNT) pathway, tumor protein p63 (TP63) pathway, other structural defects, and unknown causes 3.

Epidemiology

Ectodermal dysplasia is a rare group of disorders, with limited epidemiological data available on the subtypes. Internationally, the prevalence of all types of ectodermal dysplasia is estimated to be 7 cases per 10,000 births 4. The most common form of ED is hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (HED), with an estimated prevalence of 1.6 per 100,000 births 5.

Pathophysiology

Not all of the genetic etiologies of ectodermal dysplasia syndromes have been elucidated. However, it is clear that these disorders result from abnormal morphogenesis during fetal development of the ectoderm. Several EDs are reported to have ocular abnormalities, and these stem from errors in eye development, which occurs from approximately the third week through the tenth week of gestation 6.

Ocular tissues originate from both ectodermal and mesodermal precursors. The lens, eyelid, and corneal epithelium are derived from the surface ectoderm. The retina, ciliary body, optic nerves, and iris form from the neuroepithelium - also cells of ectodermal origin. The corneal endothelium, sclera, blood vessels, ocular muscles, vitreous body, and stroma develop from the extracellular mesenchyme - cells of mesodermal origin 7.

The homeobox gene Pax6 plays a crucial role in initiating eye development, which starts with the evagination of the optic grooves. During the fourth week of gestation, the optic grooves are transformed into optic vesicles upon neural tube closure. These optic vesicles contact the surface ectoderm and evolve into the optic cup, with the inner layer forming the retinal pigment epithelium, the middle layer forming the iris and ciliary body, and the outer layer developing into the retina. As the optic cup invaginates, the lens placode forms through the thickening of the ectoderm and eventually forms the lens vesicle upon separation from the ectoderm 6.

EDs can present with a constellation of symptoms related to errors in morphogenesis in any one of or multiple of the stages of ocular development described.

Genetics

The genetic basis for at least 80 subtypes of ED has been discovered 8. Of note, the first genetic alteration discovered as a causative mutation of ED was a loss-of-function variant of the gene ectodysplasin A (EDA) in 1996 9. Since then, defects of the EDA receptor (EDAR), the adaptor protein EDAR-associated death domain (EDARADD), and TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) have been linked to clinical phenotypes of ED 3.

These genes function in common pathways of known importance in the development of the ectodermal derivatives. The EDA gene is a part of the NFKB signaling pathway, which helps organize and differentiate ectodermal structures. The wingless-related integration site (Wnt), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and bone morphogenic proteins (BMP) are important regulators of neuroectoderm development that comprise the WNT pathway. The tumor protein 63 (TP63) pathway is important in epidermal lineage commitment for cells from the ectoderm 3.

Within the EDA/NFKB pathway, Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia, also known as ED1, is the most common and well-described syndrome in the literature 3. The majority of other hypohidrotic ED subtypes are also errors in this pathway. These conditions present with hypohidrosis, hypotrichosis, craniofacial dysmorphology, and periorbital pigmentation. Within the WNT pathway, Focal Dermal Hypoplasia (FDH or Goltz Syndrome) is well described, and this disorder presents with Short stature, facial asymmetry, narrow auditory canals, hypodontia, and sparse hair 3. Finally, within the TP63 pathway, Ankyloblepharon-Ectodermal Defects-Cleft Lip/Palate (AEC) syndrome is characterized by ankyloblepharon (fused eyelids), sparse hair, skin erosions, and cleft lip/palate 3.

Ocular Manifestations

Eyelash and Eyebrow Abnormalities

The most common eye manifestations of ED are eyelash and eyebrow changes. ED is associated with madarosis, with varying severity from mild thinning to complete lack of hair. Trichiasis is also a common ocular complication of ED, causing corneal irritation, foreign body sensation, and discomfort to the patient. This is especially common in AEC syndrome, commonly occurring with ankyloblepharon 10.

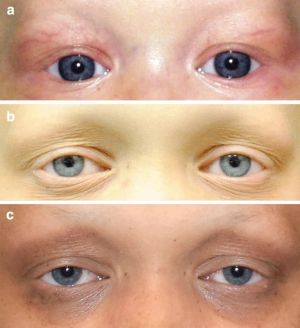

Eyelid Abnormalities

Ectropion, the outward turning of the eyelids, is a common ocular manifestation of ED. This can result in corneal exposure, chronic ocular surface irritation, and inadequate tear film distribution 11. The palpebral conjunctiva can show infiltrative and degenerative changes in patients with ectropion 12.

Ptosis is observed in many subtypes of ED, especially TP63 and EDA1. The progressive decrease in anterior lamellar tone or levator dehiscence are theorized mechanisms of acquired ptosis in ED patients 13.

Ankyloblepharon, fusion of the eyelids, is a defining feature of the Ankyloblepharon-ectodermal defects-cleft lip/palate (AEC) syndrome subtype of ED. This can result in corneal exposure, amblyopia, and trichiasis 13.

Dry Eye Disease

Dry eye is a common ocular manifestation of ED. ED causes dry eye due to abnormalities in conjunctival goblet cells, lacrimal glands, or meibomian glands, all of which contribute to maintenance of the tear film layer 14. Most commonly, there is meibomian gland deficiency (present in 95% cases of HED) 15. Loss of the lipid layer produced by these glands causes tear evaporation and ultimately dry eye. Alterations in the lipid layer of the tear film result in keratopathy. Other manifestations of ED-caused dry eye are due to lacrimal gland hyposecretion and conjunctival mucin deficiency 16.

Lacrimal Drainage System Anomalies

Anomalies of the lacrimal drainage system can be primary-acquired due to congenital malformation (i.e. punctal agenesis) or secondary-acquired due to nasolacrimal duct (NLD) obstruction 10. NLD obstruction can arise secondary to atrophic rhinitis, a common non-ocular manifestation of ED 17. However, these lacrimal drainage anomalies often go unnoticed due to the reduced tear production from lacrimal gland defects.

Ankyloblepharon-Ectodermal Defects-Cleft Lip/Palate (AEC) syndrome

AEC syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant condition associated with a mutation in the sterile alpha motif (SAM) domain of the TP63 gene. This is a disorder with key diagnostic criteria of congenital adherences of the eyelids (ankyloblepharon), cleft lip or palate, and signs of ectodermal dysplasia such as sparse hair or dental changes. Other factors in the presentation can include erythroderma, superficial skin erosion, and scalp dermatitis 18.

Ectrodactyly-Ectodermal Dysplasia-Clefting Syndrome (EEC) Syndrome

EEC Syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disorder that is linked with a mutation of the TP63 gene. This disorder presents with abnormal development of tear glands, tear ducts, and meibomian glands, which can cause excessive or impaired tear production, and consequent keratitis or conjunctivitis. EEC also commonly presents with photophobia, corneal overgrowth, and pterygium. Non-ocular aspects of the phenotype can include congenital absence of digits (ectrodactyly), cleft lip or palate, and flat nasal tip 19.

Oculo-ectodermal syndrome (OES)

Oculo-ectodermal syndrome, also known as Toriello Lacassie Droste Syndrome, is a rare condition with about 20 cases reported in the literature 20. This disorder is caused by KRAS gene variants on chromosome 12 and presents with epibulbar dermoids. The phenotype of this disorder is highly variable, with non-ocular symptoms including growth failure, lymphedema, cardiovascular defects, neurodevelopmental symptoms, arachnoid cysts in the brain, cutis aplasia congenital, seizure disorder, and rhabdomyosarcoma 21.

Due to the majority of ocular tissue rising from ectoderm, there are a wide variety of ocular manifestations possible among patients with ectodermal dysplasias. The ocular features of ED can range from mild involvement with limited symptoms to sight-threatening lesions.

Diagnosis

Clinical Diagnosis

ED is diagnosed clinically in the setting of characteristic features including hypotrichosis (sparseness of body and scalp hair), hypodontia (absent teeth), and hypohidrosis (reduced sweating). HED, the most common syndrome of ED, is often diagnosed after infancy in affected individuals with the above triad and can be further identified by the distinct facial presentations of a prominent forehead and flattened nasal bridge 22.

Laboratory testing

Genetic testing is crucial for diagnosis confirmation. Molecular testing approaches include multigene panels and serial single-gene testing. For autosomal forms, identification of EDAR, EDARADD, or WNT10A pathogenic variants can help confirm the diagnosis. In X-linked HED, sequencing of the EDA gene is performed first, followed by gene-targeted duplication/deletion analysis if no pathogenic variant is found 22.

Meibography is a novel ophthalmic examination used in the clinical diagnosis of ED, showing 100% sensitivity and specificity for the identification of X-linked HED. Infrared thermography is a non-invasive procedure that can reveal typical patterns in males affected with X-linked HED but is less sensitive (86% for adults and 67% for children). Routine ophthalmic tests like the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) and non-invasive tear film break-up time (NIBUT) are useful single routine tests in adults, showing sensitivities of 86% and 71% respectively 23.

Management

Management of ocular manifestations in ectodermal dysplasia is mainly supportive, focusing on addressing dry eye and eyelid or lash abnormalities.

Eyelid Abnormalities

As stated above, ectropion can be an ocular manifestation of ED. Ectropion can be treated successfully with ectropion blepharoplasty surgery, in which the outward-turning eyelid is returned to its normal position. While there is limited literature, one case report cites no recurrence of ectropion in a 10-month follow-up post surgical intervention 27.

Other eyelid abnormalities such as ptosis and ankyloblepharon are also managed surgically. Treatment for ptosis includes blepharoplasty or external levator advancement surgery, while treatment for ankyloblepharon is separation of the eyelids to minimize risk of occlusion amblyopia 28. Discolored eyelids may be addressed with makeup such as foundation or concealer that resembles the patient's skin tone.

Eyelash and Eyebrow Abnormalities

Madarosis in ectodermal dysplasias results from malformed or improperly developed hair follicles. Cosmetically, eyebrows may be recreated using eyebrow pencils or tattoos and eyelashes may be recreated using false eyelashes or eyelash extensions. Topically, minoxidil may be used to stimulate hair growth although may not be helpful since the hair follicles have structural abnormalities. Surgically, patients may seek hair transplantation for the eyebrows. Other eyelash abnormalities such as trichiasis or distichiasis result in complications such as corneal irritation or abrasion which can be treated by removing the hair via electrolysis, laser, or freezing probe to prevent growth from the lash follicle 29.

Dry Eye and Lacrimal Drainage Anomalies

Dry eye is very commonly found in patients with ectodermal dysplasias, often due to ectropion (managed as above) or meibomian gland alteration/dysfunction. The meibomian gland produces the outer lipid layer of the tear film and without it, the tears in the eye evaporate more easily. To manage the discomfort of dry eyes, artificial tears, ointments, or eye patches may be used. To salvage tears and improve the little tear volume that is produced, the punctum can be plugged with collagen plugs or permanent silicone plugs may be placed 29. Lacrimal drainage anomalies are often corrected with dacryocystorhinostomy or conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy with Jones tube placement 13.

General management

Treatment of non-ocular manifestations in ectodermal dysplasia follows specific management strategies for temperature maintenance and multi-organ manifestations including those involving teeth, hair, skin, limbs, and eyes 25. Temperature maintenance often involves monitoring both heat exposure and heat-generating activities in children. This is essential, as diminished sweating from hypohidrosis ED results in poor thermoregulation, overheating, and potentially febrile seizures 26. Physical interventions such as cooling caps, vests, and frequent ingestion of cold liquids can be used. Teeth can be managed via an orthodontist with early interventions such as bone grafting or dental implants and prostheses. Hair anomalies can be managed with 3% minoxidil for hair growth. Skin emollients are used for patients with xerosis or collodion-like skin.

Complications

Thermoregulation may result in hyperthermia and increased mortality in patients with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasias if not properly managed. Difficulty feeding may happen as a result of dental caries and tooth loss 25. Visual complications such as occlusion amblyopia may arise with ankyloblepharon.

Prognosis

Ectodermal dysplasias usually have a good prognosis when detected early and patients generally have a normal life span. Quality of life is generally good when management of thermoregulation and dental or skeletal issues are prioritized. In general, ocular manifestations can be well managed with drops, topicals, or surgery.

Additional Resources

- National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias - https://nfed.org/

- List of Ectodermal Dysplasia - https://edsociety.co.uk/what-is-ed/types-of-ed/alphabetical-list/

References

- Deshmukh, S., and Prashanth, S. "Ectodermal Dysplasia: A Genetic Review." International Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry, vol. 5, no. 3, Sept. 2012, pp. 197-202. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1165. Epub 5 Dec 2012.

- Freire-Maia, N. "Ectodermal Dysplasias." Human Heredity, vol. 21, no. 4, 1971, pp. 309-312.

- Wright, J. T., et al. "Ectodermal Dysplasias: Classification and Organization by Phenotype, Genotype and Molecular Pathway." American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, vol. 179, 2019, pp. 442-447.

- Mark, J. Barry, et al. "Ectodermal Dysplasias."

- Nguyen-Nielsen, M., et al. "The Prevalence of X-Linked Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia (XLHED) in Denmark, 1995–2010." European Journal of Medical Genetics, vol. 56, no. 5, 2013, pp. 236-242.

- Edward, D. P., and Kaufman, L. M. "Anatomy, Development, and Physiology of the Visual System." Pediatric Clinics of North America, vol. 50, no. 1, Feb. 2003, pp. 1-23.

- Creuzet, S., et al. "Neural Crest Derivatives in Ocular and Periocular Structures." International Journal of Developmental Biology, vol. 49, no. 2-3, 2005, pp. 161-171.

- Pagnan, N. A. B., and Visinoni, Á. F. "Update on Ectodermal Dysplasias Clinical Classification." American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, vol. 164A, no. 10, 2014, pp. 2415-2423. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36616.

- Dev, A., et al. "Ectodermal Dysplasia – An Overview and Update." Indian Dermatology Online Journal, vol. 15, 2024, pp. 405-414.

- Kaercher, T. "Ocular Symptoms and Signs in Patients with Ectodermal Dysplasia Syndromes." Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, vol. 242, 2004, pp. 495-500.

- Zhang, X., et al. "Lower Lid Ectropion in Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia." Case Reports in Ophthalmology Medicine, vol. 2015, 2015, article 952834.

- Chen, X., et al. "Clinical Features, Surgical Outcomes and Genetic Analysis of Ectodermal Dysplasia with Ocular Diseases." International Journal of Ophthalmology, vol. 15, 2022, pp. 1062-1070.

- Landau Prat, D., et al. "Ocular Manifestations of Ectodermal Dysplasia." Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, vol. 16, no. 1, 2021, article 197. doi:10.1186/s13023-021-01824-2.

- Arita, R., et al. "New Insights Into the Lipid Layer of the Tear Film and Meibomian Glands." Eye & Contact Lens, vol. 43, no. 6, Nov. 2017, pp. 335-339. doi:10.1097/ICL.0000000000000369.

- Ekins, M. B., and Waring, G. O. "Absent Meibomian Glands and Reduced Corneal Sensation in Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia." Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, vol. 18, 1981, pp. 44-47.

- Callea, M., et al. "Extended Overview of Ocular Phenotype with Recent Advances in Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia." Children, vol. 9, no. 9, 2022, article 1357. doi:10.3390/children9091357.

- Sachidananda, R., et al. "Anhidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia Presenting as Atrophic Rhinitis." The Journal of Laryngology & Otology, vol. 118, no. 7, July 2004, pp. 556-557. doi:10.1258/0022215041615173.

- Tajir, M., et al. "Ankyloblepharon-Ectodermal Defects-Cleft Lip-Palate Syndrome Due to a Novel Missense Mutation in the SAM Domain of the TP63 Gene." Balkan Journal of Medical Genetics, vol. 23, no. 1, 2020, pp. 95-98. doi:10.2478/bjmg-2020-0013.

- Bharati, A., et al. "Ectrodactyly-Ectodermal Dysplasia Clefting Syndrome: A Case Report of Its Dental Management with 2 Years Follow-Up." Case Reports in Dentistry, vol. 2020, 2020, article 8418725. doi:10.1155/2020/8418725.

- Boppudi, S., et al. "Specific Mosaic KRAS Mutations Affecting Codon 146 Cause Oculoectodermal Syndrome and Encephalocraniocutaneous Lipomatosis." Clinical Genetics, vol. 90, 2016, pp. 334-342. doi:10.1111/cge.12775.

- Figueiras, D. D. A., et al. "Oculoectodermal Syndrome: Twentieth Described Case with New Manifestations." Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia, vol. 91, 2016, pp. 160-162. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164409.

- Wright, J. T., et al. "Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia." GeneReviews, University of Washington, Seattle, 28 Apr. 2003, updated 27 Oct. 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1112/.

- Kaercher, T., et al. "Current Eye Research." vol. 40, no. 9, 2015, pp. 884-890. doi:10.3109/02713683.2014.96786.

- Mellerio, J., and Greenblatt, D. "Hidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia 2." GeneReviews, University of Washington, Seattle, 25 Apr. 2005, updated 15 Oct. 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1200/table/ed2.T.ectodermal_dysplasias_in_the_diffe/.

- Majmundar, V. D., and Baxi, K. "Ectodermal Dysplasia." StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2024. Accessed 13 Oct. 2024. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563130/.

- Huang, S. X., et al. "EDA Mutation as a Cause of Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia: A Case Report and Review of the Literature." Genetics and Molecular Research, vol. 14, 2015, pp. 10344-10351.

- Zhang, X., et al. "Lower Lid Ectropion in Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia." Case Reports in Ophthalmology Medicine, vol. 2015, 2015, article 952834. doi:10.1155/2015/952834.

- Phelps, P., et al. "Ankyloblepharon." EyeWiki. Accessed 15 Oct. 2024. Available from: https://eyewiki.org/Ankyloblepharon.

- National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias. "How Ectodermal Dysplasias Affects Eyes and How to Treat." Accessed 13 Oct. 2024. Available from: https://nfed.org/treat/medical-treatment-options/.

- Warning , Aaron, and Vatinee Y. Bunya. “Embryology of the Eye and Ocular Adnexa.” EyeWiki, 30 Nov. 2021, eyewiki.org/Embryology_of_the_Eye_and_Ocular_Adnexa.