Ocular Manifestations of Alkaptonuria

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Alkaptonuria (AKU) is a rare autosomal recessive aminoacidopathy that results from the absence of the homogentisate 1,2 dioxygenase enzyme (homogentistic acid oxidase). AKU becomes symptomatic typically after the fourth decade of life, independent of genre, usually debuting with multiple arthropathy, genitourinary tract obstruction, cardiovascular problems, or bilateral conjunctival pigmentation or ear cartilage pigment deposition.

Disease Entity

Synonyms: Hereditary ochronosis, homogenization acid oxidase deficiency, black urine disease [1][2][3]

Disease

Alkaptonuria (AKU) is a rare autosomal recessive aminoacidopathy of the phenylalanine/tyrosine metabolism that is caused by the absence of the homogentisic acid (HGA) 1,2-dioxidase, resulting in HGA accumulation in the body and excretion of this in the urine.[4] [5][6] Organs affected secondarily include large joints, the cardiovascular system, kidneys, skin, eyes, and various glands.[7][8][9] It was first described as a heritable entity by Sir Archibald Garrod in 1902; a disease from which he later formulated the concept of “inborn errors of metabolism."[2][4][6]

Alkaptonuria results in the classic triad of dark-colored urine, ochronosis, and ochronotic arthropathy.[10]

Etiology

As Garrod originally identified, AKU has an autosomal recessive genetic trait[2][4] whose hallmark is the absence of activity of the 1,2-dioxygenase of the homogenstisic acid, enzyme located in the liver.[5] The gene responsible for this disease is located in chromosome 3 (3q2).[3]

Epidemiology

At least 1000 affected individuals have been described in the literature; this is likely an underestimate.[11] The worldwide incidence of AKU is estimated to be between 1 in 250,000 to 1 million people. [12][13] However, it is known that Slovakia and the Dominican Republic are the two countries with the highest reported incidence of alkaptonuria, estimated to be 1 in 19,000 people. [14][15]

Risk Factors

The principal risk factor for the presence of AKU is an affected sibling or parent. Because it is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, there is a 50% chance of being an asymptomatic carrier, and a 25% chance of not being a carrier of the trait. [16]

General Pathology

Individuals with AKU develop dark-colored urine, ochronosis (bluish-black coloration in the connective tissue) in conjunctiva and ear cartilage, and ochronotic arthropathy, mainly affecting large joints and the spine.[10][16]

Pathophysiology [4][7][17]

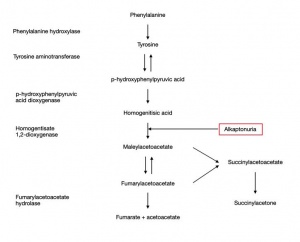

AKU is a hereditary disorder that results from the absence of the homogentisate 1,2 dioxygenase enzyme, predominantly produced by liver hepatocytes, which catalyzes the breakdown of HGA, an intermediate in the tyrosine degradation pathway.

Phenylalanine is hydroxylated to tyrosine due to HGA action. In AKU this absent enzyme causes massive accumulation of HGA in collagenous tissues, especially in the nose, ear, cheek, conjunctiva, muscles insertions, cornea and sclera.

The formation of the melanin-like HGA polymer, which deposits over time in the tissues, is result of an oxidative process via the metabolism of benzoquinone acetic acid. (Figure 1)

The ochronotic pigment attachment to the connective tissue gives rise to a multisystem disorder.

Often, ocular clinic is the initial manifestation of the disease, and eye ochronosis usually presents at the average age of 30 years old. [18]

Primary prevention [17]

- Early diagnosis and clinical suspicion are necessary to a prompt recognition of the disease; discoloration of diapers often offers the earliest opportunity to suspicion.

- Education of the medical professionals regarding this disease.

- Screening of siblings and parents for the affected gene.

- Genetic counseling.

Diagnosis

History

Alkaptonuria is not routinely diagnosed unless an extended newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism is performed,[19] or a positive past medical history of dark or brown urine in the patient or relatives is brought up.[2] During the teenage years or early adulthood, the disease usually remains asymptomatic.[7][17]

AKU becomes symptomatic typically after the fourth decade of life, independent of genre, usually debuting with multiple joint arthropathy,[16][20] genitourinary tract obstruction, cardiovascular problems, [13] or bilateral conjunctival pigmentation or ear cartilage pigment deposition.[4][7]

Physical examination

External Exam

- Constant dark urine with oxidation [17]

- Severe spondyloarthropathy in peak adulthood; weight-bearing joints are most commonly affected (ie. spine, hips and knees.)[21]

- Renal stones.

- Progressive kyphoscoliosis. [22]

- Congestive heart failure.[8][23]

- Other than joint damage, manifestations of AKU include those due to high HGA [17]

Slit-lamp exam

1. Most frequent ocular signs

- Bluish-dark bilateral scleral lesions in interpalpebral areas; nasal and temporal perilimbal near the rectus muscle insertion (Osler’s sign). [9][24][25][26]

- “Oil drop-like” spots in the cornea at the level of Bowman's membrane, [27] which can progress over time.[9][25][28]

- Dilated conjunctival vessels can be found supplying the pigmented areas of the conjunctiva. [29]

- Four types of scleral pigmentation patterns have been described:

- Small "vermiform" or "tube-like" pigment deposits.

- Pinguecula-like pigmentation.

- Dot-like pigmentation.

- Laminar structures. [9][29]

2. Less common

- Refraction: different degrees of corneal astigmatism can be observed; whether against-the-rule, irregular astigmatism, or with-the-rule. The astigmatism is thought to have a progressive nature associated with increasing peripheral corneal thinning and astigmatism in the axis of the lesion. [25][28][29][30][31]

- Metabolic keratopathy

- Glaucoma has been reported in several occasions in these patients due to various conditions, such as:

- 1) pigment accumulation in the iridocorneal angle,

- 2) secondary to central retinal venous occlusion; and

- 3) primary open angle glaucoma without additional findings. [25][26][32][33][34]

- Macular epiretinal membrane has also been reported. [25][29]

Symptoms

Systemic [17]

- Progressive arthritic pain affecting all synovial joints, large and small.

- Painful spinal disease.

- Sleep disturbances.

Ocular [4][9]

- Ocular foreign body sensation.

Clinical diagnosis

Clinical findings of alkaptonuria include darkening of urine when exposed to air due to oxidation, and chronic joint pain. Patients can also be referred after black articular cartilage is noted during orthopedic surgery. [16]

Diagnostic procedures [4][16][17][35]

- Chromatographic urinalysis for the presence of HGA is the gold standard for diagnosis confirmation.

- Urine color change upon alkalization.

- N-telopeptide of type I collagen detection in urine (due to the bone metabolism).

- Ocular lesion biopsies: description with hematoxylin-eosin-stained slide elastotic degeneration of collagen fibers admixed with yellowish waxy globules and fiber-like deposits slightly refractive.

Diagnostic innovations give a unique characterization of AKU as a disease. Magnetic resonance imaging can exhibit a thickening of the Achilles tendon, [36] echocardiogram can reveal severe cardiac valve calcification, stenosis or dilatation, [16][20] positron emission tomography with isotope bone scans can identify the extent of arthropathy, [37] and kidney stones can be detected through ultrasonography. [16]

Laboratory test [4][16][17][35]

Genetic testing to determine homozygous or compound heterozygotes state; HGD gene identification.

Identification of bi-allelic pathogenic variants in HGD on molecular genetic testing is not required to establish the diagnosis in a proband. However, molecular genetic testing is needed in order to provide carrier testing and prenatal test result interpretation for at-risk family members. Sequence analysis of HGD gene is performed first, followed by gene-targeted deletion/duplication analysis if only one or no pathogenic variant is found. In the Slovak population, four pathogenic variants have been reported which are the cause of disease in 80% of the population (c.481G>A, c.457dup, c.808G>A, and c.1111dup). In the United States, the analysis of these variants is recommended initially, and then the sequencing of the entire gene if the cause is found. Sequencing reveals causal mutation in 90% of cases.[37]

Differential diagnosis [16]

Arthritis due to alkaptonuria resembles ankylosing spondylitis or rheumatoid arthritis, but the sparing of the sacroiliac joint differs from the former, and radiographic appearance differs from both.

Management

Medical therapy [7][17]

- Ascorbic acid supplementation.

- Low protein diet.

- Lifestyle counseling.

- Physiotherapy.

- Pain management.

- Palliative care.

- Aortic stenosis may necessitate valve replacement.

- Treatment of prostate and renal stones may include surgical intervention.

- Cardiac surveillance after 40 years with echocardiogram or cardiac tomography in order to identify valve calcifications or stenosis and coronary vessels calcification.

Medical follow up [17]

Surveillance after the fourth decade of life for treatable complications is of vital importance in these patients, such as signs of heart disease, kidney stones, renal insufficiency and prostatolithiasis.

Surgery [17]

- Joint replacement surgery.

- Orthopedic spine surgery.

Prognosis [7]

Alkaptonuria does not reduce life expectancy, nevertheless it importantly affects the quality of life of the patients if their complications are not addressed.

Additional Resources

- Alkaptonuria - American Academy of Ophthalmology

- Alkaptonuria - Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD)

- Alkaptonuria - National Organization for Rare Disorders

- "The Patient Who Turned To The Dark Side" - AAO.org

References

- ↑ Virchow RL: Rudolph Virchow on ochronosis.1866. Arthritis and rheumatism 1966, 9(1):66-71.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Garrod AE: Inborn Errors of Metabolism. Nature 1909, 81(2073):96-97.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Pollak MR, Chou YH, Cerda JJ, Steinmann B, La Du BN, Seidman JG, Seidman CE: Homozygosity mapping of the gene for alkaptonuria to chromosome 3q2. Nature genetics 1993, 5(2):201-204.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Chevez Barrios P, Font RL: Pigmented conjunctival lesions as initial manifestation of ochronosis. Archives of ophthalmology 2004, 122(7):1060-1063.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 La Du BN, Zannoni VG, Laster L, Seegmiller JE: The nature of the defect in tyrosine metabolism in alcaptonuria. The Journal of biological chemistry 1958, 230(1):251-260.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Prasad C, Galbraith PA: Sir Archibald Garrod and alkaptonuria -'story of metabolic genetics'. Clinical genetics 2005, 68(3):199-203.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Mistry JB, Bukhari M, Taylor AM: Alkaptonuria. Rare diseases 2013, 1:e27475.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Lok ZS, Goldstein J, Smith JA: Alkaptonuria-associated aortic stenosis. Journal of cardiac surgery 2013, 28(4):417-420.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Lindner M, Bertelmann T: On the ocular findings in ochronosis: a systematic review of literature. BMC ophthalmology 2014, 14:12.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 Tharini G, Ravindran V, Hema N, Prabhavathy D, Parveen B: Alkaptonuria. Indian journal of dermatology 2011, 56(2):194-196.

- ↑ Rovensky J, Urbánek T, Oľga B, Gallagher J: Alkaptonuria and Ochronosis; 2015.

- ↑ Phornphutkul C, Introne WJ, Perry MB, Bernardini I, Murphey MD, Fitzpatrick DL, Anderson PD, Huizing M, Anikster Y, Gerber LH et al: Natural history of alkaptonuria. The New England journal of medicine 2002, 347(26):2111-2121.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Gaines JJ, Jr.: The pathology of alkaptonuric ochronosis. Human pathology 1989, 20(1):40-46.

- ↑ Srsen S, Muller CR, Fregin A, Srsnova K: Alkaptonuria in Slovakia: thirty-two years of research on phenotype and genotype. Molecular genetics and metabolism 2002, 75(4):353-359.

- ↑ Goicoechea De Jorge E, Lorda I, Gallardo ME, Perez B, Perez De Ferran C, Mendoza H, Rodriguez De Cordoba S: Alkaptonuria in the Dominican Republic: identification of the founder AKU mutation and further evidence of mutation hot spots in the HGO gene. Journal of medical genetics 2002, 39(7):E40.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 16.8 Introne WJ, Gahl WA: Alkaptonuria. In: GeneReviews((R)). edn. Edited by Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, Amemiya A. Seattle (WA); 1993.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 17.10 Ranganath LR, Jarvis JC, Gallagher JA: Recent advances in management of alkaptonuria (invited review; best practice article). Journal of clinical pathology 2013, 66(5):367-373.

- ↑ Sallmann L: VI. über die Augenpigmentierung bei endogener Ochronose. Ophthalmologica 1926, 60(3-4):164-171.

- ↑ Arnold GL: Inborn errors of metabolism in the 21(st) century: past to present. Annals of translational medicine 2018, 6(24):467.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 Steger CM: Aortic valve ochronosis: a rare manifestation of alkaptonuria. BMJ case reports 2011, 2011.

- ↑ Helliwell TR, Gallagher JA, Ranganath L: Alkaptonuria--a review of surgical and autopsy pathology. Histopathology 2008, 53(5):503-512.

- ↑ Perry MB, Suwannarat P, Furst GP, Gahl WA, Gerber LH: Musculoskeletal findings and disability in alkaptonuria. The Journal of rheumatology 2006, 33(11):2280-2285.

- ↑ Ranganath LR, Cox TF: Natural history of alkaptonuria revisited: analyses based on scoring systems. Journal of inherited metabolic disease 2011, 34(6):1141-1151.

- ↑ Osler W: OCHRONOSIS: THE PIGMENTATION OF CARTILAGES, SCLEROTICS, AND SKIN IN ALKAPTONURIA. The Lancet 1904, 163(4192):10-11.

- ↑ Jump up to: 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Okutucu M, Aslan MG, Findik H, Yavuz G: Glaucoma With Alkaptonuria as a Result of Pigment Accumulation. Journal of glaucoma 2019, 28(7):e112-e114.

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 D AC, Malbran E: [Ocular Ochronosis]. Archivos de oftalmologia de Buenos Aires 1963, 38:299-305.

- ↑ SMITH JW: OCHRONOSIS OF THE SCLERA AND CORNEA COMPLICATING ALKAPTONURIA: REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE AND REPORT OF FOUR CASES. Journal of the American Medical Association 1942, 120(16):1282-1288.

- ↑ Jump up to: 28.0 28.1 Cheskes J, Buettner H: Ocular manifestations of alkaptonuric ochronosis. Archives of ophthalmology 2000, 118(5):724-725.

- ↑ Jump up to: 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Damarla N, Linga P, Goyal M, Tadisina SR, Reddy GS, Bommisetti H: Alkaptonuria: A case report. Indian journal of ophthalmology 2017, 65(6):518-521.

- ↑ Ehongo A, Schrooyen M, Pereleux A: [Important bilateral corneal astigmatism in a case of ocular ochronosis]. Bulletin de la Societe belge d'ophtalmologie 2005(295):17-21.

- ↑ Demirkilinc Biler E, Guven Yilmaz S, Palamar M, Hamrah P, Sahin A: In Vivo Confocal Microscopy and Anterior Segment Optic Coherence Tomography

- ↑ Kampik A, Sani JN, Green WR: Ocular ochronosis. Clinicopathological, histochemical, and ultrastructural studies. Archives of ophthalmology 1980, 98(8):1441-1447.

- ↑ Ashton N, Kirker JG, Lavery FS: Ocular Findings in a Case of Hereditary Ochronosis. The British journal of ophthalmology 1964, 48:405-415.

- ↑ Bacchetti S, Zeppieri M, Brusini P: A case of ocular ochronosis and chronic open-angle glaucoma: merely coincidental? Acta ophthalmologica Scandinavica 2004, 82(5):631-632.

- ↑ Jump up to: 35.0 35.1 Aliberti G, Pulignano I, Schiappoli A, Minisola S, Romagnoli E, Proietta M: Bone metabolism in ochronotic patients. Journal of internal medicine 2003, 254(3):296-300.

- ↑ Jiang L, Cao L, Fang J, Yu X, Dai X, Miao X: Ochronotic arthritis and ochronotic Achilles tendon rupture in alkaptonuria: A 6 years follow-up case report in China. Medicine 2019, 98(34):e16837.

- ↑ Jump up to: 37.0 37.1 Vinjamuri S, Ramesh CN, Jarvis J, Gallagher JA, Ranganath LL: Nuclear medicine techniques in the assessment of alkaptonuria. Nuclear medicine communications 2011, 32(10):880-886.