Ocular Candidiasis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Ocular candidiasis is a well-known complication of candidemia. Candidemia has become increasingly prevalent in the hospital setting as a complication of surgery and with increased use of parenteral nutrition, central venous catheters, and treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics. Systemic candidemia can lead to ocular candidiasis via hematogenous seeding of retinal and choroidal blood vessels and can have various ocular manifestations.

Etiology

Ocular candidiasis can occur from exogenous or endogenous routes. Exogenous methods include trauma or direct inoculation from surgery or other procedures. Exogenous ocular candidiasis is uncommon in North America and Europe, and more commonly seen in tropical regions such as India. Endogenous ocular candidiasis occurs from hematogenous seeding in the eye from transient fungemia, and while still rare, occurs most commonly in patients who are severely immunocompromised or who have indwelling catheters. Studies from Asian countries had a 2.5 fold higher concordant prevalence of candida endophthalmitis compared with studies from European and American countries (3.6% vs 1.4%) in patients with candidemia. [1]

Risk Factors

Risk factors of candidemia include long term intravenous (IV) therapy, indwelling catheters, abdominal surgery, trauma, immunosuppression, malignancy, diabetes, debilitation, and intravenous drug abuse.[2]

Risk factors for ocular candidiasis include infection with Candida albicans species and use of total parental nutrition have been found to confer greater risk in multiple studies,[3][4][5][1] persistent candidemia, and neutropenia during the preceding 2 weeks.[4] The presence of ocular symptoms, and corticosteroid use were also correlated with ocular involvement.[3][4][5]

History

Ocular candidiasis occurs in males and females equally.[6][7] It is most commonly seen in patients who are severely immunocompromised or have long-term indwelling lines and have risk factors as listed above.

Epidemiology

In a review by Breazzano et al., 38 studies including 7472 patients who underwent ophthalmological screening for ocular candidiasis after positive blood cultures of fungemia or candidemia were reviewed. 9.2% of screened patients had chorioretinal lesions and 1.6% had endophthalmitis. The incidence of Candida endophthalmitis varies based on how it is defined. Prior to 1994, the median incidence rate of Candida endophthalmitis was 28.1% compared to 0.9-1.2% post-1994 when a classification system requiring vitreous involvement was established.[8]

Current recommendations by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) suggests that all individuals with positive Candida blood cultures undergo routine ophthalmological screening for endophthalmitis.[9]

Physical examination

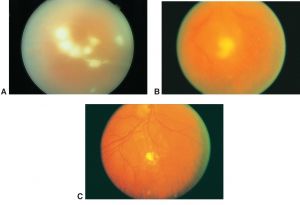

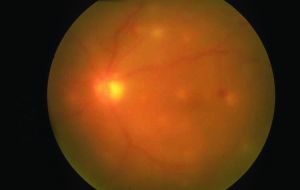

Ocular examination of patients with ocular candidiasis can reveal focal yellow-white or white chorioretinal lesions that can be single or multiple. The classic manifestation of Candida endophthalmitis is a chorioretinal lesion with overlying vitritis and vitreous haze if the infection and associated inflammation extends into the vitreous.[8] Patients may also have vitreous abscesses or vitreal “fluff balls” which are indicative of Candida endophthalmitis. Other exam findings include corneal haze, anterior chamber cell, retinal hemorrhages, exudates, cotton wool spots, and vascular sheathing. In cases of endophthalmitis, hypopyon, scleritis, and optic-nerve involvement may also be seen.[3][8][12]

Symptoms

Patients with ocular candidiasis can experience blurry vision, floaters, photosensitivity, and ocular pain.[3][8]

Clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis of ocular candidiasis is clinical and includes identifying predisposing risk factors from the patient’s medical history, clinical setting, and fundus findings on exam. Candida chorioretinitis is characterized by focal yellow-white or white chorioretinal lesions without vitreal involvement. Candida endophthalmitis presents with vitritis and is often described as “fluff balls” or “string-of-pearls” within the vitreous body.[12]

Differential diagnosis

Early ocular candidiasis may demonstrate nonspecific lesions such as cotton wool spots and hemorrhages. Infectious lesions with necrotic centers can resemble Roth spots, which can be found in other conditions including diabetic or hypertensive retinopathy, thrombocytopenia, and hematologic malignancies. Septic emboli that may lead to endogenous Candida endophthalmitis can also be found in bacteremia and must be differentiated from bacterial endophthalmitis.[13] Larger choroidal lesions can mimic intraocular lymphoma and other masqueraders. Other infections such as syphilis, tuberculosis and toxoplasmosis may also be considered. When the retina cannot be visualized, other causes of vitritis also need to be considered including other infectious uveitis entities and autoimmune uveitis. Old vitreous hemorrhage masquerading as vitritis is also a consideration and most likely, would present without other inflammatory features.

Laboratory test

Laboratory testing for ocular candidiasis consists of blood cultures showing growth of Candida species. Urine cultures and cultures from intravenous lines may also be helpful in source identification. Studies have shown that Candida non-albicans species cause a higher incidence of candidemia than Candida albicans species (54.4% vs. 45.6%, respectively),[14] however fungemia with Candida albicans has been shown in multiple studies to pose the greatest risk for developing ocular candidiasis.[3][4]

Diagnostic procedures

In cases where the clinical diagnosis is unclear, vitreous tap to obtain intraocular fluid can be performed for gram staining and cultures. Intraocular culture specimens can also be obtained during pars plana vitrectomy. While this is an effective method for obtaining intraocular culture specimens, this is often only performed in cases of severe endophthalmitis in conjunction with antifungal intravitreal injections for treatment. When a patient has characteristic ocular candidiasis findings and known systemic candidiasis, ocular culture is not needed and this can be defined as probable ocular candidiasis.[6] Positive growth of Candida species in conjunction with characteristic fundus features as described above is defined as proven ocular candidiasis.[4][12]

B-scan ultrasound should be performed in cases where the retina is obscured by media opacity.

In early cases, fluorescein angiogram may demonstrate chorioretinitis.

Treatment

If possible, removal of the inciting cause of systemic candidemia is advised (e.g. removal or replacement of indwelling lines/catheters). Systemic antifungal therapy is targeted based on culture susceptibilities, and options include intravenous amphotericin B, azoles (e.g. voriconazole, fluconazole) and echinocandins (e.g. micafungin, caspofungin).[2][12][15] [16]In general, initial therapy with an intravenous echinocandin is recommended for both non-neutropenic and neutropenic patients with candidemia. Fluconazole may be used as an alternative in non-neutropenic patients who are not critically ill. However, as neutropenic patients are often placed on fluconazole prophylaxis, there has been an increasing number of Candida species with reduced susceptibility. In patients who are clinically stable, have repeat negative blood cultures, and have Candida species susceptible to fluconazole, step-down therapy to oral fluconazole may be pursued after 5-7 days. Access to various medications will be dictated by region and involvement of infectious disease specialists is recommended.

A review of contemporary studies suggest that ocular candidiasis responds well with systemic medical management. In the review by Breazzano et al., chorioretinitis was identified in 78 patients with resolution on systemic monotherapy. Of the 19 endophthalmitis cases included in the review, 12 patients were treated with systemic therapy alone, 6 received combined systemic and local therapy (2 pars plana vitrectomy, 2 combined pars plana vitrectomy/tap and injection, and 2 tap and injection), and 1 patient improved solely with IV catheter removal. Six of the 12 patients with endophthalmitis treated with systemic monotherapy died. Of the 6 surviving endophthalmitis patients treated with systemic monotherapy, complete ocular resolution occurred. The patients who received both local intervention and systemic treatment achieved resolution with 3 patients having permanent vision loss.[8] These results may be influenced by the severity of disease.

Intravitreal Injection

With macula-involving Candida chorioretinitis, lesions threatening vision, patients with Candida endophthalmitis, or in patients with worsening ophthalmic examination, systemic antifungal agents plus intravitreal injections are classically pursued. In the review by Breazzano et al., macular involving chorioretinitis showed a response to systemic medical management alone,[8] but intravitreal injections are frequently used as adjunctive therapy given current Infectious Diseases Society of America recommendations.[9] Intravitreal management depends upon the risks and benefits of invasive intervention versus medical treatment alone within the overall clinical context as described above.[8]

Treatment with either amphotericin B 5-10 μg/0.1 mL or voriconazole 100 μg/0.1 mL may be utilized. The half-life of amphotericin in the vitreous is much longer than voriconazole and should be taken into consideration. Access to different medications may vary by region. Successful off-label use of intravitreal caspofungin has been reported.[17][18]

Pars Plana Vitrectomy

Vitrectomy should be considered in cases of severe vitritis to decrease the burden of infection and remove fungal abscesses, or if complications such as retinal detachment develop.[8]

Complications

Overall mortality in one series was 57%.[2] Ocular complications include retinal detachment, vision loss, intraocular hemorrhage, and glaucoma. An increase in ocular candida endophthalmitis has been recently documented in COVID patients treated with intensive steroid therapy. An high index of suspicion should be considered if clinical findings are suggestive of intraocular infection. [19]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Phongkhun K, Pothikamjorn T, Srisurapanont K, et al Prevalence of Ocular Candidiasis and Candida Endophthalmitis in Patients With Candidemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2023 May 24;76(10):1738-1749.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 Fraser VJ, Jones M, Dunkel J, Storfer S, Medoff G, Claiborne Dunagan W. Candidemia in a tertiary care hospital: Epidemiology, risk factors, and predictors of mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15(3):414-421. doi:10.1093/clind/15.3.414

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Shah CP, McKey J, Spirn MJ, Maguire J. Ocular candidiasis: A review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(4):466-468. doi:10.1136/bjo.2007.133405

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Son HJ, Kim MJ, Lee S, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of patients with ocular involvement of candidemia. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):1-13. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222356

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Donahue SP, Greven CM, Zuravleff JJ, et al. Intraocular Candidiasis in Patients with Candidemia: Clinical Implications Derived from a Prospective Multicenter Study. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(7):1302-1309. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(94)31175-4

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Khalid A, Clough LA, Symons RCA, Mahnken JD, Dong L, Eid AJ. Incidence and clinical predictors of ocular candidiasis in patients with Candida fungemia. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2014;2014. doi:10.1155/2014/650235

- ↑ Abusamra K. Candidiasis. In: Foster CS, Anesi SD, Chang PY, eds. Uveitis: A Quick Guide to Essential Diagnosis. Springer International Publishing; 2021:189-191. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-52974-1_41

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Breazzano MP, Day HR, Bloch KC, et al. Utility of Ophthalmologic Screening for Patients with Candida Bloodstream Infections: A Systematic Review. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(6):698-710. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0733

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Executive Summary: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;62(4):409-417. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1194

- ↑ Flynn HW Jr. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Endogenous yeast (Candida) endophthalmitis. https://www.aao.org/image/endogenous-yeast-candida-endophthalmitis-2 Accessed April 25, 2021.

- ↑ Stone D. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Candida endophthalmitis. https://www.aao.org/image/icandidai-endophthalmitis-2 Accessed April 25, 2021.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Oude Lashof AML, Rothova A, Sobel JD, et al. Ocular manifestations of candidemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(3):262-268. doi:10.1093/cid/cir355

- ↑ Rodríguez-Adrián LJ, King RT, Tamayo-Derat LG, Miller JW, Garcia CA, Rex JH. Retinal lesions as clues to disseminated bacterial and candidal infections: Frequency, natural history, and etiology. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82(3):187-202. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000076008.64510.f1

- ↑ Horn DL, Neofytos D, Anaissie EJ, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 2019 patients: Data from the prospective antifungal therapy alliance registry. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(12):1695-1703. doi:10.1086/599039

- ↑ Khan FA, Slain D, Khakoo RA. Candida endophthalmitis: Focus on current and future antifungal treatment options. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(12 I):1711-1721. doi:10.1592/phco.27.12.1711

- ↑ Pérez-González N, Rodríguez-Lagunas MJ, Calpena-Campmany AC, Bozal-de Febrer N, Halbaut-Bellowa L, Mallandrich M, Clares-Naveros B. Caspofungin-Loaded Formulations for Treating Ocular Infections Caused by Candida spp. Gels. 2023 Apr 20;9(4):348.

- ↑ Yadav HM, Thomas B, Thampy C, Panaknti TK. Management of a case of Candida albicans endogenous endophthalmitis with intravitreal caspofungin. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65(6):529-531. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_781_16

- ↑ Danielescu C, Cantemir A, Chiselita D. Successful treatment of fungal endophthalmitis using intravitreal caspofungin. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2017;80(3):196-198. doi:10.5935/0004-2749.20170048

- ↑ Shroff, Daraius; Narula, Ritesh1; Atri, Neelam; Chakravarti, Arindam1; Gandhi, Arpan2; Sapra, Neelam3; Bhatia, Gagan; Pawar, Shraddha R1; Narain, Shishir. Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis following intensive corticosteroid therapy in severe COVID-19 disease. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 69(7):p 1909-1914, July 2021. | DOI: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_592_21