Morbihan Disease

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD)

- ICD 11: BD93.1Y: Lymphoedema secondary to other specified cause

Overview

Morbihan disease (MD), also known as solid persistent facial edema, lymphedema rosacea, morbus Morbihan and Morbihan syndrome, is a rare condition characterized by chronic, progressive, non-pitting edema (+/- erythema) of the upper two-thirds of the face, notably the periorbital tissue, forehead, glabella, nose, and cheeks, that may result in facial disfigurement and visual field narrowing [1] [2] [3]

History of the disease

MD was first observed in the 1950s. [4] [5] It was named after Morbihan, a department in Brittany, France where the findings were described by a dermatologist, Dr Robert Degos.

Anatomy

MD affects the upper two thirds of the face, including:

- Forehead

- Glabella

- Periorbital region: both preseptal and pretarsal tissue

- Cheeks

- Nose

Pathogenesis

The cause of MD remains unknown. Many authors propose that MD is caused by lymphatic dysregulation, chronic inflammation, or both. The hypotheses fall under several categories:

- There is an imbalance between lymphatic production and drainage [6][7]

- Mast cells obstruct dermal lymphatics or cause dermal fibrosis. [8][9][3]

- Peri and intra-lymphatic granulomas obstruct lymphatic drainage [10][11]

- Chronic inflammatory mediators, released due to underlying autoimmune dysregulation or infection, cause vascular wall damage and breakdown of connective tissue within the dermis leading to persistent exudation and resultant edema.[12][13][14][15][16]

- Contact urticaria, in response to topical irritants, triggers local inflammation resulting in insufficient lymphatic drainage in individuals with pre-existing lymphatic drainage defects[7]

The relationship between Morbihan disease, rosacea and acne has been theorized due to histopathologic similarities. [14] The limitation of this hypothesis, however, is that many patients with MD do not have rosacea or acne.[1][2][17] The association between rosacea, acne and MD remains unclear.

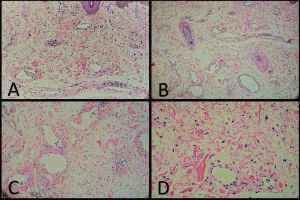

Histopathology

The histopathology is non-specific in MD. [9][18][19][11][20][1][15][21][2][14][22][23][10][16][24][25][8][3]

The most common histopathologic findings reported include:

- Perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic and histiocytic infiltration

- Presence of mast cells

- Perifollicular fibrosis

- Dilated lymphatic channels in the dermis

- Dermal edema

Other, less commonly described, findings include:

- Perifollicular and peri-lymphatic epithelioid granulomas

- Lymphatic histiocytic infiltration

- Telangiectasia

- Dilated blood vessels

- Plasma cells

- Giant cells

- Neutrophils

- Increased collagen spacing and thickness

- Sebaceous gland hypertrophy/hyperplasia

- Chronic folliculitis

Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of MD are unknown.

Risk factors

- Male > Female

- Middle age

- Ethnicity: Caucasian/white

- Most of the cases described in the literature were of Caucasian individuals, followed by Asian individuals (Japanese, Chinese, Korean). Few reports in other ethnicities.[1]

- Other: exposure to sun and woodworking dust.[26][27]

History

Patients note an insidious onset of upper facial swelling. Pertinent points on history include:

- Swelling of upper face, with or without redness

- Insidious onset, progressive [18]

- Non-painful, non-pruritic [1]

- Possible visual impairment from increased lacrimation or mass effect causing ptosis and visual field narrowing [19][27][2]

- Edema that is generally not position dependent, although may be described as worse in the morning [19]

- May be associated with hot sensation of face, facial flushing [28][3], or psychosocial distress due to cosmetic disfigurement[1]

Physical examination

Physical examination findings include:

- Non-pitting, solid edema affecting the upper two-thirds of the face.

- Erythema of the overlying skin.[1] Erythema is typically ill-defined, present in discrete patches, or solitary plaques.

- Findings may be symmetric or asymmetric, unilateral or bilateral [1][11]

- Typically, preserved visual acuity and eye exam within normal limits [20][23]

- May lead to visual impairment / visual field narrowing due to ptosis from mass effect and lacrimation [19][27][2]

- Can cause significant facial disfigurement [1]

- Peau d’orange skin texture (few cases) [27][19][20]

- Bilateral chemosis of the anterior segment has been reported in one case [1]

- Signs of rosacea, telangiectasia, papules, pustules, granulomas, nodules [3][1][29]

Diagnosis

There are no diagnostic criteria for MD. It is a diagnosis of exclusion.[3] Investigations are used to rule out other causes of facial edema and are ordered at the discretion of the healthcare provider based on the patient’s specific presentation (see differential diagnoses below).

Laboratory test

The mainstays in investigations are bloodwork, radiographic imaging, and biopsy. Laboratory bloodwork can rule out systemic disease. Preoperative orbital computed tomography (CT) can be used to assess for orbital tumours. Biopsy of the skin can be used to rule out other dermatologic disease.

| Investigations to consider | Rationale & Findings |

| Blood work | Note: Laboratory investigations are generally normal in MD

|

| Imaging |

|

| Biopsy

|

|

| Other |

|

Differential diagnosis

| Differential diagnosis of chronic facial edema / eyelid swelling [31][23][20][15][11][19][32] | |

| Inflammatory |

|

| Infectious |

|

| Neoplastic |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

Management

Systemic associations

Morbihan disease may be associated with rosacea, acne or both. [20][14][11][15]

Systemic manifestations

There are no systemic manifestations of MD.

Management of eyelid edema

There is no gold standard for the treatment of this rare disease.

Patients can be recommended avoidance potential triggers (see “prevention”).

Interventions result in variable clinical improvement. Recurrence or progression can be seen after treatment discontinuation.[1] A combination of interventions have been used with some success,[22][33][29][34][35] although a systematic review found no superior effect with combination therapy on outcomes and a greater risk of adverse effects.[1] Some case reports and case series have shown promising results.

Management in the literature

| |

| Local |

|

| Systemic |

|

| Surgical | |

| Alternative therapy |

|

It has been hypothesized that medical therapy often fails due to impaired local delivery systems at the site of chronic inflammation and interstitial edema in MD patients.[15] Erythema and inflammatory signs may respond to medications, but edema often persists.[15] Combining surgical debridement with anti-inflammatory medical therapy may improve treatment response.[15]

Future considerations for management include the use of immunosuppressant medications to target lymphocyte populations. Azathioprine and omazilumab have been suggested as potential therapies.[15][38][3]

Prognosis

Prevention

No modifiable risk factor has been identified.[3] Patients can be recommended avoidance of sun and irritating cosmetics as supportive to treatment.[16][18]

Prognosis

Without treatment, MD is unlikely to resolve spontaneously.[26] The condition is localized to the face and has no known systemic manifestations. MD is often refractory to treatment; however, most cases show at least partial response to conventional treatment.[1] A review article on the topic suggests patients may benefit from 4- to 6- months of tetracycline-based antibiotics with the risk of side effects weighed against the benefits of treatment.[1] Oral steroids were correlated with recurrence or progression. Male gender correlated with lack of complete response to treatment.[1] Patients who undergo debulking respond to treatment although response may be partial.[1] Approximately 10% of patients have recurrence or progression of disease.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 Boparai RS, Levin AM, Lelli GJ Jr. Morbihan Disease Treatment: Two Case Reports and a Systematic Literature Review. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35(2):126-132

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Kim JE, Sim CY, Park AY, et al. Case Series of Morbihan Disease (Extreme Eyelid Oedema Associated with Rosacea): Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Ann Dermatol. 2019;31(2):196-200

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Yvon C, Mudhar HS, Fayers T, et al. Morbihan Syndrome, a UK Case Series. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36(5):438-443

- ↑ Degos R, Civatte J, Beuve-Méry M. Nouveau cas d’œdème érythémateux facial chronique. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph 1973;80:257

- ↑ Schimpf A. Dermatitis frontalis granulomatosa. Derm Wschr 1956;133:120

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Smith LA, Cohen DE. Successful Long-term Use of Oral Isotretinoin for the Management of Morbihan Disease: A Case Series Report and Review of the Literature. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(12):1395-1398

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Hattori Y, Hino H, Niu A. Surgical Lymphoedema Treatment of Morbihan Disease: A Case Report. Ann Plast Surg. 2021;86(5):547-550

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Veraldi S, Persico MC, Francia C. Morbihan syndrome. Indian Dermatol Online J 2013;4:122–4.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ramirez-Bellver JL, Perez-Gonzalez YC, Chen KR, et al. Clinicopathological and Immunohistochemical Study of 14 Cases of Morbihan Disease: An Insight Into Its Pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41(10):701-710.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Nagasaka T, Koyama T, Matsumura K, Chen KR. Persistent lymphoedema in Morbihan disease: formation of perilymphatic epithelioid cell granulomas as a possible pathogenesis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33(6):764-7

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Belousova IE, Kastnerova L, Khairutdinov VR, Kazakov DV. Unilateral Periocular Intralymphatic Histiocytosis, Associated With Rosacea (Morbihan Disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2020;42(6):452-454

- ↑ Camacho-Martinez F, Winkelmann RK. Solid facial edema as a manifestation of acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:129–30

- ↑ Cribier B. Physiopathologie de la rosacée [Physiopathology of rosacea]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2014 Sep;141 Suppl 2:S158-64

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Kuhn-Régnier S, Mangana J, Kerl K, et al. A Report of Two Cases of Solid Facial Edema in Acne. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7(1):167-174

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 Carruth BP, Meyer DR, Wladis EJ, et al. Extreme Eyelid Lymphedema Associated With Rosacea (Morbihan Disease): Case Series, Literature Review, and Therapeutic Considerations. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3S Suppl 1):S34-S38

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Olvera-Cortés V, Pulido-Díaz N. Effective Treatment of Morbihan's Disease with Long-term Isotretinoin: A Report of Three Cases. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(1):32-34

- ↑ Chaidemenos G, Apalla Z, Sidiropoulos T. Morbihan disease: successful treatment with slow-releasing doxycycline monohydrate. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(2):e68-e69.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Wohlrab J, Lueftl M, Marsch WC. Persistent erythema and edema of the midthird and upper aspect of the face (morbus morbihan): evidence of hidden immunologic contact urticaria and impaired lymphatic drainage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(4):595-602

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 19.8 19.9 Bechara FG, Jansen T, Losch R, Altmeyer P, Hoffmann K. Morbihan's disease: treatment with CO2 laser blepharoplasty. J Dermatol. 2004;31(2):113-115

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 Bernardini FP, Kersten RC, Khouri LM, Moin M, Kulwin DR, Mutasim DF. Chronic eyelid lymphedema and acne rosacea. Report of two cases. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(12):2220-3

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Chalasani R, McNab A. Chronic lymphedema of the eyelid: case series. Orbit. 2010;29(4):222-6

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Kuraitis D, Coscarart A, Williams L, Wang A. Morbihan disease: a case report and differentiation from Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26(6)

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Lai TF, Leibovitch I, James C, Huilgol SC, Selva D. Rosacea lymphoedema of the eyelid. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2004;82(6):765-7

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Tsiogka A, Koller J. Efficacy of long-term intralesional triamcinolone in Morbihan's disease and its possible association with mast cell infiltration. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31(4):e12609

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Vasconcelos RC, Eid NT, Eid RT, Moriya FS, Braga BB, Michalany AO. Morbihan syndrome: a case report and literature review. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):157-159

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Hu SW, Robinson M, Meehan SA, Cohen DE. Morbihan disease. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18(12):27

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Ranu H, Lee J, Hee TH. Therapeutic hotline: Successful treatment of Morbihan's disease with oral prednisolone and doxycycline. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(6):682-685.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Cabral F, Lubbe LC, Nobrega MM, Obadia DL, Souto R, Gripp AC. Morbihan disease: a therapeutic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(6):847-850

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Aboutaam A, Hali F, Baline K, Regragui M, Marnissi F, Chiheb S. Morbihan disease: treatment difficulties and diagnosis: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:226

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Pflibsen LR, Howarth AL, Meza Rochin A, Decapite T, Casey WJ 3rd, Mansueto LA. A Navajo Patient with Morbihan's Disease: Insight into Oculoplastic Treatment of a Rare Disease. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(9):e3090.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Messikh R, Try C, Bennani B, Humbert P. Efficacité des diurétiques dans la prise en charge thérapeutique de la maladie de Morbihan: trois cas [Efficacy of diuretics in the treatment of Morbihan's disease: three cases]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2012;139(8-9):559-563

- ↑ West, B. A., Hoesly, P. M., LeBoit, P. E., & Homer, N. A. (2022). Cutaneous angiosarcoma presenting as bilateral periorbital edema. Orbit, 42(6), 621–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/01676830.2022.2056901

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Heibel HD, Heibel MD, Cockerell CJ. Successful treatment of solid persistent facial edema with isotretinoin and compression therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6(8):755-757

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Welsch K, Schaller M. Combination of ultra-low-dose isotretinoin and antihistamines in treating Morbihan disease - a new long-term approach with excellent results and a minimum of side effects [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 5]. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;1-4

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Rebellato PR, Rezende CM, Battaglin ER, Lima BZ, Fillus Neto J. Syndrome in question. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(6):909-11

- ↑ Kutlay S, Ozdemir EC, Pala Z, Ozen S, Sanli H. Complete Decongestive Therapy Is an Option for the Treatment of Rosacea Lymphedema (Morbihan Disease): Two Cases. Phys Ther. 2019;99(4):406-410.

- ↑ Okubo A, Takahashi K, Akasaka T, Amano H. Four cases of Morbihan disease successfully treated with doxycycline. J Dermatol. 2017;44(6):713-716

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Kafi P, Edén I, Swartling C. Morbihan syndrome successfully treated with omalizumab. Acta Derm Venereol 2019;99:677–678.

- ↑ Lee AG. Pseudotumor cerebri after treatment with tetracycline and isotretinoin for acne. Cutis. 1995 Mar;55(3):165-8

- ↑ Yu X, Qu T, Jin H, Fang K. Morbihan disease treated with Tripterygium wilfordii successfully. J Dermatol. 2018;45(5):e122-e123.