Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) is a RNA virus that causes aseptic meningitis when it is acquired, and chorioretinitis and other devastating neurologic sequelae in the congenital form.

Etiology

Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV) is a single-stranded RNA arenavirus that is endemic in rodents. Human infection likely occurs by contact with infected rodents or their excretions (saliva, urine, nesting material, and droppings) through inoculation of contaminated materials into broken skin, via the eyes or mouth . [1]The common house mouse, Mus musculus, is both the natural host and reservoir for the virus, which is spread via vertical transmission.

Most infections in humans likely go unrecognized and are instead attributed to the flu, on occasion they can have aseptic meningitis or encephalitis. The prevalence of LCMV infection has been estimated to be between 2-5%, with higher prevalence in humans living in extreme poverty. [2] Most infections occur in the fall and winter, indicative of the time mice move into homes.[3]

Women who become infected with LCMV during pregnancy may pass the infection on to the fetus. Infections occurring during the first trimester may result in fetal death and pregnancy termination, while in the second and third trimesters, birth defects can develop. Infants infected In utero can have many serious and permanent birth defects, including chorioretinitis, mental retardation, hearing loss, intracerebral calcification, macro or micro-cephaly, and hydrocephaly.

Risk Factors

Exposure to infected rodents (mice, hamsters, guinea pigs).

Pathophysiology

Both acquired and congenital LCMV diseases are a result of both the infection and the host response to the infection.

Acquired LCMV Infection

The virus is transmitted in an aerosolized form and deposited into the lung parenchyma and enters the blood stream and travels to other organs. LCMV demonstrates a tropism towards neuroblasts and ultimately replicates in the meninges, choroid plexus, and ventricular ependymal linings. The virus continues to replicate and causes the symptoms of aseptic meningitis. [4] Tissue inflammation from the host immune response is the cause of the disease symptoms.[5] Human-human transmission has not been documented, except in the case of infected organ transplantation. [6]

Congenital LCMV Infection

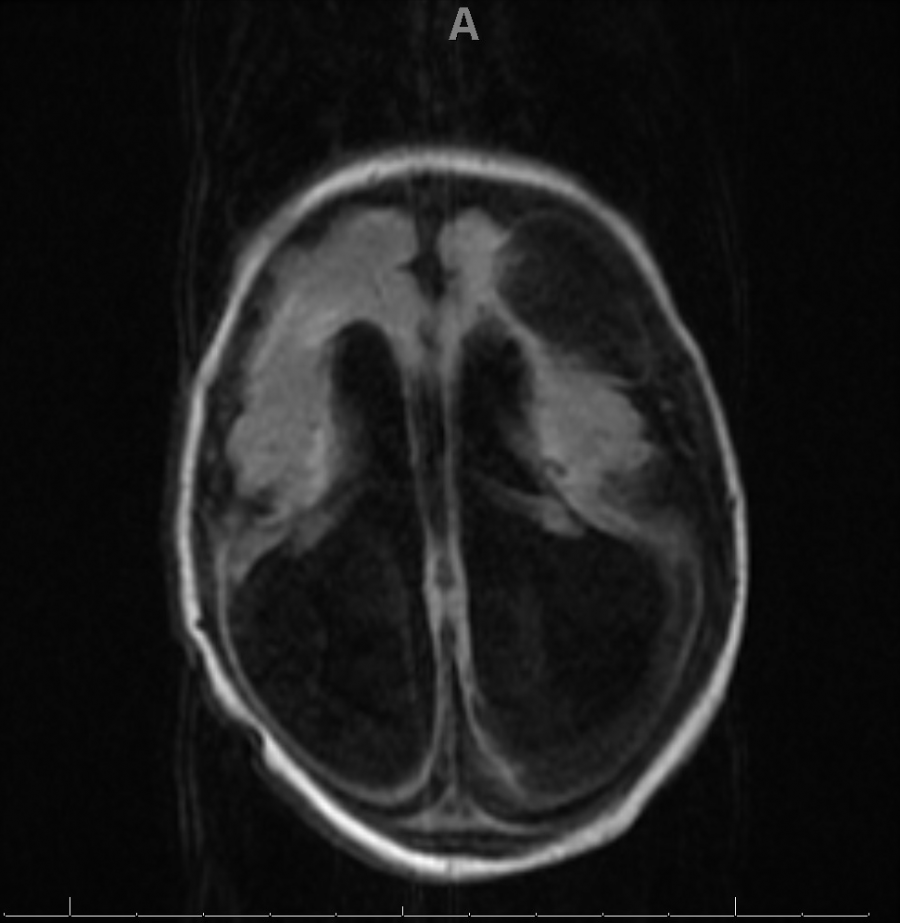

Congenital LCMV is the result of vertical transmission, most often trans placentally, though rarely a fetus may acquire the infection intrapartum. Neuropathologic studies have demonstrated that mononuclear cell infiltrates in the meninges, choroid plexus, and ependymal cells. The inflammatory response is largely driven by T-cells. [7] Either macrocephaly or microcephaly commonly occurs in neonates. Macrocephaly is typically a result of inflammation at the cerebral aqueduct blocking the ventricular system. Microcephaly is usually the result of immune-mediated destruction of brain tissue as well as the virus mediated failure of brain tissue. [8][5]

Primary prevention

Pregnant women should take extra precaution to avoid rodents during pregnancy.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is primarily made via serology (serum IgM and IgG against LCMV)

History

LCMV was first discovered in 1933 as a cause of meningo-encephalitis, resulting in patient death. [9] Congenital LCMV was first reported in England in 1955 and first reported in the United States in 1993.[10] [11] LCMV is also known to cause sudden death in clusters of patients after solid organ transplants.

Physical examination

A dilated fundus examination with scleral depression is recommended. The patients are usually children in their early years of life, sent for ocular examination due to clinical suspicion of congenital TORCH infection.

Signs/Symptoms

Acquired LCMV

Acquired LCMV infection is typically a biphasic disease. Roughly one-third of patients are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms. Symptoms of acquired LCMV infection include fever, headache, nausea/vomiting, sore throat, malaise, myalgia, and cough. In the second phase of infection, there is likely neurologic manifestations of the disease which are characteristic of aseptic meningitis. The entire clinical course is typically one to three weeks. Patients who acquire the disease through solid organ transplantation or pregnant women typically will have a more severe disease course. [6]

Around 10% of patients with aseptic meningitis in a study of hospitalized had been infected with LCMV [12] and was more commonly seen in pre-1960 era. It is rare to see an LCMV infection in present time. Transverse myelitis, Guillan-Barré syndrome, and hydrocephalus have been noted in these patients. [13]

There can be abnormal lab values which include leukopenia, transaminitis, thrombocytopenia. In addition, there are infiltrates seen in the lung on chest X-ray or chest CT. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis will reveal CSF pleocytosis (unusual in other viral infections). Eosinophila in the CSF fluid has also been noted, along with decreased glucose and elevated protein concentrations in the CSF. [14]

Congenital LCMV

Congenital LCMV is more likely to have neurologic and ocular manifestations rather than other systemic disease. In pregnant women, the infection can result in abortion, neonatal meningitis, or the following signs:

- Microcephaly

- Macrocephaly

- Ventriculomegaly

- Periventricular calcifications

- Cerebellar hypoplasia

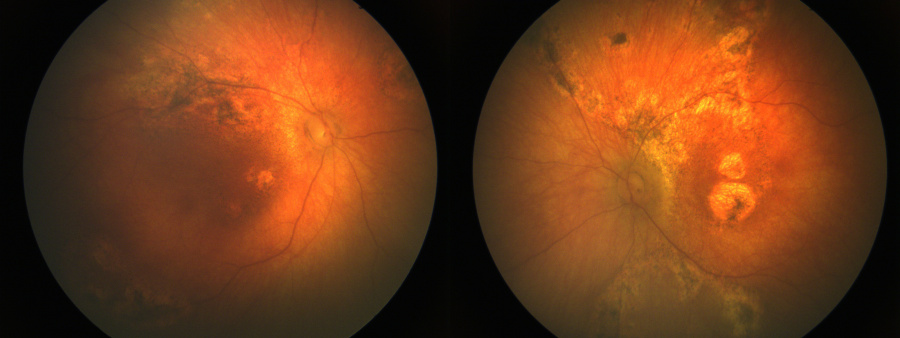

- Chorioretinitis

The ocular manifestations include:

- Chorioretinal scars in the periphery

- Chorioretinal scars in macula

- Optic atrophy

- Nystagmus

- Esotropia

- Exotropia

Optic atrophy, nystagmus, esotropia, exotropia have been seen only in patients with chorioretinal scarring. Microphthalmia and cataracts have also been noted. [15]

Diagnostic procedures

A lumbar puncture may be performed which may reveal abnormalities in the CSF. MRI can reveal pertinent findings (as described above).

Laboratory test

Blood work up and a spinal tap may be indicated. Laboratory diagnosis is usually made by detecting IgM and IgG antibodies in the CSF and serum. Virus can be detected by PCR or virus isolation in the CSF during the acute stage of illness. [16]

There can be other laboratory abnormalities in the first phase of the acquired LCMV infection. The laboratory abnormalities include leukopenia, transaminitis, and thrombocytopenia.

Differential diagnosis

Acquired LCMV

The differential diagnosis for acquired LCMV includes all causes of aseptic meningitis, influenza, mononucleosis, mumps meningoencephalitis, Lyme, and Listeria.

Congenital LCMV

The differential diagnosis for congenital LCMV is primarily the TORCH infections with a few non-infectious etiologies.

| Infectious | Non-infectious |

| CMV | Aicardi Syndrome |

| Toxoplasmosis | Choroideremia |

| Zika | Gyrate Atrophy |

| HSV-1 | |

| HSV-2 | |

| Syphilis | |

| LCMV | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | |

| Rubella | |

| Parvovirus B-19 |

Management

Medical therapy

There is no known medical therapy for LCMV. Treatment is primarily supportive. Ribavirin has been used in certain cases, however the role of ribavirin in the treatment remains unclear. [6]

Medical follow up

Patients affected by congenital LCMV should have multi-disciplinary follow-up with an ophthalmologist, neurologist, physical therapy, and occupational therapy.

Complications

Vision loss in patients with congenital LCMV is often very severe. Given the pathophysiology, brain function is also severely affected. Children with microcephaly nearly always have severe developmental delays, epilepsy, and quadriparesis. However, those with only cerebellar hypoplasia may have slight learning disability and ataxia.

Prognosis

The prognosis for acquired LCMV is generally good with mortality <1%.

The prognosis of congenital LCMV, however, is poor. The mortality rate of congenital LCMV has been reported to be 35% in a meta-analysis by two years of age. [8]

LCMV infection has also been implicated in several fatal results in recipients of organ transplants. [17]

Online resources

http://www.eyerounds.org/cases/91-LCMV.htm

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/cmv/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/lcm/index.html

References

- ↑ Emonet S, Retornaz K, Gonzalez JP, de Lamballerie X, Charrel RN. Mouse-to-human transmission of variant lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(3):472–5.

- ↑ Cantey JB. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus. In: Cantey JB, ed. Neonatal Infections. Springer International Publishing; 2018:135-137. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-90038-4_15

- ↑ Bonthius DJ, Barton LL, Klein de Licona H, Bonthius NE, Karacay B. Arenaviruses. In: Barton LL, Friedman NR, editors. The Neurological Manifestations of Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Immunodeficiency Syndromes. Totown, NJ: Humana Press; 2008.

- ↑ Buchmeier MJ, Zajac AJ. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. In: Ahmed R, Chen I, editors. Persistent Viral Infections. New York: Wiley; 1999. pp. 575–605.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Bonthius DJ. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: A prenatal and postnatal threat. Advances Pediatrics. 2009;56:75–86

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Fischer SA, Graham MB, Kuehnert MJ, et al. Transmission of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus by organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(21):2235-2249. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa053240

- ↑ Bonthius DJ, Nichols B, Harb H, Mahoney J, Karacay B. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection of the developing brain: critical role of host age. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(4):356-374. doi:10.1002/ana.21193

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Wright R, Johnson D, Neumann M, et al. Congenital lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus syndrome: a disease that mimics congenital toxoplasmosis or Cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatrics. 1997;100(1):E9. doi:10.1542/peds.100.1.e9

- ↑ Armstrong C, Lillie RD. Experimental Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis of Monkeys and Mice Produced by a Virus Encountered in Studies of the 1933 St. Louis Encephalitis Epidemic. Public Health Reports (1896-1970). 1934;49(35):1019-1027. doi:10.2307/4581290

- ↑ Komrower GM, Williams BL, Stones PB. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis in the Newborn. Probable Transpiacental Infection. Lancet. Published online 1955:697-698.

- ↑ Larsen PD, Chartrand SA, Tomashek KM, et al. Hydrocephalus complicating lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 1993;12(6):528–531.

- ↑ Meyer HM Jr, Johnson RT, Crawford IP, Dascomb HE, Rogers NG. Central nervous system syndromes of “viral” etiology: a study of 713 cases, Am J Med, 1960, vol. 29 (pg. 334-47)

- ↑ Tindall GT, Gladstone LA. Hydrocephalus as a sequel to lymphocytic choriomeningitis, Neurology, 1957, vol. 7 (pg. 516-8)

- ↑ Chesney PJ, Katcher ML, Nelson DB, Horowitz SD. CSF eosinophilia and chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus meningitis, J Pediatr, 1979, vol. 94 (pg. 750-2)

- ↑ Strausbaugh LJ, Barton LL, Mets MB. Congenital Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Infection: Decade of Rediscovery. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001;33:370–374. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/321897.

- ↑ https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/lcm/diagnosis/index.html

- ↑ Lendino A, Castellanos AA, Pigott DM, Han BA. A review of emerging health threats from zoonotic New World mammarenaviruses. BMC Microbiol. 2024 Apr 4;24(1):115.