Lefort Fractures

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

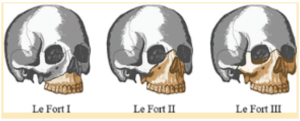

Initially described in 1901 by French surgeon René Le Fort (1869-1951), LeFort fractures represent a group of midface fractures that occur following blunt trauma and follow areas of structural weakness. Common etiologies include assault, facial trauma in contact sports, motor vehicle accidents (MVA), or falls from significant heights. Le Fort fractures are classified by direction of fracture pattern: horizontal, pyramidal, or transverse and the mid facial bones involved. These fractures are designated Le Fort I, Le Fort II, and Le Fort III respectively. Physical exam is important; however, diagnosis and classification are largely dependent on radiological findings. These fractures are often present asymmetrically. Significantly, a pterygoid fracture is highly sensitive for a Le Fort fracture and is present in all three fracture variations. However, it is not a specific finding and presence of pterygoid plate involvement does not confirm a Le Fort fracture. Management involves surgical correction for significantly displaced fractures with clinical: function and/or esthetic consequences. Careful attention should be paid to evaluate for additional facial or intracranial injuries as Le Fort fractures are frequently seen in association with concomitant life threatening injuries given the mechanisms of injury and the degree of force necessary to produce these fracture patterns.[1]

| Medical Diagnosis | ICD-10 Code |

|---|---|

| Le Fort I | S02.411 |

| Le Fort II | S02.412 |

| Le Fort III | S02.413 |

Historical Perspective

René Le Fort was a prominent French surgeon in the late 19th and early 20th century. Following medical school graduation at age 22, Le Fort pursued a career in military medicine before returning to his alma mater to teach. His prior military career prompted Le Fort to experiment with facial trauma to better identify fracture patterns following blunt injury. Le Fort would apply varying degrees of blunt force to severed and attached cadaver heads with a wooden club, a metal shaft, and reportedly a cannon ball. He reportedly conducted 35 experiments and, with the resulting data, published three manuscripts in 1901 describing the fracture patterns that have come to be termed LeFort I, II, and III. Although modern technology and imaging modalities have identified fractures that do not fall precisely into the Le Fort classification scheme, this terminology is still routinely used to summarize and communicate midface injuries. More recent literature suggests a revised classification scheme with four categories would be a more accurate description of midfacial fractures. These four categories include a high horizontal fracture (which includes LeFort II and LeFort III), low horizontal fracture (includes LeFort I), sagittal fracture (includes midline and paramidline fractures), and alveolar fracture. More recently, an adaptation of Le Fort fractures has been included in the Practical Classification of Orbital & Orbitofacial fractures (Orbital Fractures: Principles, Concepts & Management. SundarG)

Disease Entity

Disease

Le Fort fractures describe facial fracture patterns secondary to blunt force trauma that involve the pterygoid plate, which can result in separation of the facial skeleton from the skull base. Frequently asymmetrical and incomplete, Le Fort II and Le Fort III fractures involve the orbit with ophthalmological consequences while Le Fort I typically does not.

Epidemiology

Incidence of maxillofacial trauma has increased globally over the last several decades, believed to be in part due to complex social and societal factors. Increased urbanization with higher road density and faster and multiple vehicular traffic has resulted in an increased incidence of MVAs while improved vehicular safety has resulted in lower mortality with higher morbidity. It has also been proposed that more aggressive interpersonal conflict has resulted in an increase in rate of head and face trauma. Several studies have identified assault as the leading cause of midface fractures in developed countries. In their 2014 analysis, Arslan et al. found the most common etiology of both midface and maxillary fractures to be assault (39.7%), followed by falls (27.9%) and MVAs (27.2%). In contrast, MVAs appear to be the leading cause of midface fractures in developing nations.[2]

Several studies have indicated a higher incidence of facial fractures in men relative to women, with ratio of 2.0-2.8:1. When sub-analyzed by decade of life, men were found to have a higher incidence of facial fracture each decade through age 70. Beyond age 70, facial injuries were more common in women.

Midface fractures have overtaken mandibular fractures as the most common facial fracture, with some studies estimating they represent up to 50-71% of facial fractures. Prior studies have suggested that LeFort fractures account for 10-20% of all facial fractures. In their study of over 9,500 maxillofacial cases, Gassner et al. identified that LeFort I fractures were responsible for approximately 2.9% of midface fractures and 2.1% of all facial fractures; LeFort II fractures for 3.0% of midface fractures and 2.2% of all facial fractures; and LeFort III for 2.1% of midface fractures and 1.5% of all facial fractures. Arslan’s 2014 analysis supported these findings, suggesting that LeFort I, II, and III were responsible for 0.3%, 1.1%, and 2.7%, of facial fractures, respectively.[3]

Concomitant injuries are frequently seen with Le Fort fractures due to the traumatic mechanism of injury and degree of blunt force required. The stability of the patient’s airway is an important consideration given the need for surgical intervention. Ocular injury has been reported in literature to be present in 24-28% of facial fractures. Cervical spine fractures have been reported in 1.3% of all facial fractures and 4% of facial fractures resulting from MVA. Recent studies have suggested a higher rate of traumatic brain injuries (TBI) associated with Le Fort fractures relative to other facial fracture patterns. A recent analysis of 1172 patients by Lucke-Wold et al found an increase rate of TBIs requiring neurosurgical intervention in patients with Le Fort II and III injuries. These findings were supported by additional studies which identified that approximately 9-10% of patients with maxillofacial trauma were found to have intracranial hemorrhage.[4]

Etiology[1][5]

Le Fort fractures are caused by blunt force trauma, which is divided into low velocity mechanisms and high velocity mechanisms. Low velocity mechanisms include falling from standing height, blunt force assault, or contact sports, such as soccer or rugby. High velocity mechanisms are most commonly secondary to motor vehicle accidents, but may include high speed sports such as mountain biking, cycling, and skiing.

Le Fort Type I

Of no particular significance to ophthalmologists, Le Fort Type I fractures classically occur from a downward force against the upper teeth. 56% of these fractures occur from low velocity mechanisms.

Le Fort Type II & III

Le Fort Type II and III fractures are most commonly from high velocity mechanisms. Le Fort II fractures classically occur from force delivered at the level of the nasal bones. Le Fort III fractures classically occur from force delivered at the level of the nasal bridge and orbits. They may be associated with orbital soft tissue, globe and optic nerve injuries.

Risk Factors[5][6]

- Drugs or alcohol use is associated with more severe fractures

- Motor vehicle accidents

- Absence of safety devices such as seat belts or helmets

- Contact sports

- High velocity sports

Pathophysiology[5][6][7][8]

The human skull is comprised of 22 distinct bones. Of these 22 bones, 14 are considered facial and 8 are cranial. The facial bones include two maxilla, two zygomas, two nasal bones, the mandible, two lacrimal bones, two palatine bones, two inferior nasal conchae, and the vomer. The facial bones and the supporting soft tissue serve several important purposes, including protection of the central nervous system (including the brain and eyes) and structure for the oropharyngeal and tracheal functions of mastication, ventilation, and phonation.

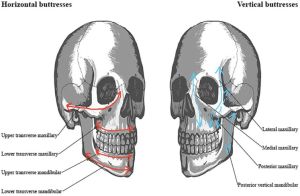

An important anatomical consideration for trauma are facial buttresses, which can be divided into vertical buttresses and horizontal buttresses. These buttresses are areas of thicker bone and provide support for soft tissue. They also present the best location to attach rigid fixation plates during operative repair. The vertical buttresses resist vertical forces, such as forces of mastication or vertical impacts. The horizontal structures provide support for the vertical structures and resist some horizontal forces, but are weaker than the vertical pillars.

The vertical buttresses are paired and define the vertical height of the face; they include the following from anteromedial to posterolateral:

1.Nasomaxillary/Medial Maxillary: These buttresses course superiorly from the anterior maxillary alveolar process over the nasomaxillary junction to the glabella

2.Zygomaticomaxillary/Lateral Maxillary: These buttresses course superotemporally from the lateral maxillary alveolar process to the zygoma. At this point, this buttress bifurcates and includes the lateral orbital wall and the posterior zygomatic arch.

3.Pterygomaxillary/Posterior Maxillary: These buttresses course along the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus and extending to the base of the pterygoids.

4.Vertical Mandibular/Posterior Vertical: These buttresses course from the vertical ramus of the mandible to the temporomandibular joint.

Horizontal buttresses provide cross member stability to the facial skeleton. They consist of the following from superior to inferior:

1.Frontal Bar: This buttress courses along the supraorbital ridges and the thickened region of frontal bone enveloped between them.

2.Upper Transverse Maxillary: These buttresses course along the infraorbital rim and includes the orbital floor and insertion site of the medial canthal tendon.

3.Lower Transverse Maxillary: This buttress courses along the central inferior maxillary margin.

4.Upper Transverse Mandibular: This buttress courses along the superior margin of the mandible and extends laterally.

5.Lower Transverse Mandibular: This buttress courses along the inferior margin of the mandible and extends laterally.

Le Fort fractures are fracture patterns following the relatively weak areas of the facial skeleton. Le Fort fractures are classified into three types, but all involve the pterygoid plate, which can cause separation of the facial skeleton from the skull base.

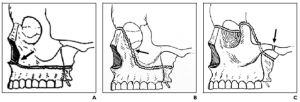

Le Fort Type I (Horizontal)

Le Fort Type I fracture is a horizontal fracture of the lower maxilla from the midface, without orbital involvement, causing a freely mobile tooth-baring upper jaw and hard palate. This classically occurs from a downward force to the upper jaw (lower maxilla), causing a fracture across the anterior maxilla, through the lateral nasal wall and pterygoid plates.

Le Fort Type II (Pyramidal)

Le Fort Type II fracture is a pyramidal shaped fracture along the nasal bridge, involving the inferomedial orbital rim and orbital floor, and causes separation of the midface from the skull base. This occurs from force at the level of the nasal bones (middle maxilla), causing fractures along the nasal bridge, frontal maxilla, lacrimal bones, orbital floor and inferior rim near the inferior orbital foramen, through the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus, and through the pterygoid plates.

Le Fort Type III (Transverse, aka Craniofacial Dysfunction)

Le Fort III fracture, also called a craniofacial dysfunction, is a transverse fracture that creates posterior orbital fractures to separate the entire midface from the skull base, sparing the optic canal. This occurs from force delivered at the orbital level and nasal bridge (upper maxilla) causing fractures along the medial orbital wall, through the nasolacrimal groove and ethmoid bones, along the orbital floor and inferior orbital fissure, along the lateral orbital wall, through zygomatic arch, ethmoid, and pterygoid processes.

Facial fractures rarely follow these fracture patterns, but rather are composed of a combination of fracture types. One study found that only 24% of facial fractures follow these patterns. Most cases partially resemble Le Fort fractures but are associated with other midface fractures, while 20% are comminuted and did not follow these lines at all. Motor vehicle accidents usually cause panfacial traumas due to the severity of impact.

Primary prevention[5]

Prevention of Le Fort fractures involve avoiding facial trauma especially with high impact. Implementing general safety guidelines and using safety devices such as seat belts, car seats, appropriate facial protective devices (sports) and helmets can reduce the risk and severity of injuries.

Diagnosis

History[6][9][10][11][12]

Patients suffering from Le Fort fractures may be concussed or unconscious and therefore unable to respond to a history. When possible, patients should be inquired about the cause and timing of injury, and force involved. It is important to inquire about the cause of injury because patients presenting with Le Fort fractures may be experiencing domestic violence, child abuse, or elder abuse. Patients should also be questioned about any sequelae including diplopia, paresthesia, difficulties/changes in ocular and oral function and in dental occlusion, and symptoms of airway obstruction (e.g. dyspnea, stridor) . A review of systems and past medical history is also recommended. A neurological assessment is indicated for all patients, as any changes in mental status or unconsciousness are the alarming signs for further neurological investigations. Document any involved use of alcohol or illicit substances.

Physical examination[5][6][9][11][12][13]

Patients with Le Fort fractures and other maxillofacial trauma should first be examined using the advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocols. This includes prioritizing the evaluation of the patient’s airway, breathing, circulation, deficits in neurological function, and exposure and environment control (i.e. primary survey). Efforts should also be made to stabilize the cervical spine especially in suspected Le Fort II and III fractures.

After critical conditions have been examined and managed with the primary survey, the maxillofacial fractures should be assessed during the secondary survey. At this time, the patient should also be inspected for facial lacerations, and bone fractures and/or dislocations. Carefully visualize and palpate surrounding facial bones including nasal bones, orbital rims, maxilla, and mandible. If the patient was in a motor vehicle accident, assess for possible penetrating foreign bodies. A complete cranial nerve examination is also required, with emphasis on cranial nerves II, III, IV, V, VI, and VII.

An ophthalmic evaluation should also be performed for Le Fort II and III fractures. Limited movement in extraocular motilities may suggest damage to ocular muscles and possible orbital floor fractures. Other ocular abnormalities that may present with Le Fort fractures, especially type III, include diplopia, chemosis, enophthalmos, traumatic telecanthus, and transient vision impairment. (See “Ophthalmic and Orbital Exam" for more details)

An intraoral evaluation should also be performed, where the dentition, periodontium, and dental occlusion are assessed. Intraoral structures should be palpated to assess integrity with bidigital maxillary instability assessment. A chest x-ray should be performed for any unaccounted missing dentition to rule out dental aspiration.

- Ophthalmic and Orbital Exam:

- Visual acuity

- Ocular alignment & motility exam

- Visual field

- Pupil exam

- Intraocular pressure

- Eyelid assessment

- Fundoscopy

- Medial and Lateral Canthal assessment

- Exophthalmometry

- Other Craniofacial Examination:

- Airway assessment

- Palpitation of facial bone suture lines for fractures

- Visual assessment for presence of soft tissue laceration and ecchymosis

- Trigeminal and Facial nerves assessment

- Intraoral examination and palpation of dentition, periodontium, and dental occlusion

- Intra- and extra-nasal examination

- Neck exam

Signs and symptoms[5][6][9][11][12][13]

There are many mutual signs and symptoms across the three types of Le Fort fractures. Below is a list of both common general and type-specific (but not exclusive) signs and symptoms:

Common to all types:

- Buccal vestibule and palatal ecchymosis

- Alterations in dental occlusion

Common to Le Fort I:

- Lower maxilla and upper labial edema

- Ecchymosis of the hard and/or soft palate, including at the junction

- Mobility of maxillary dentition

- Mobility of maxilla

- Unilateral or bilateral epistaxis

- Palatal laceration and/or fractures

- Maxillary paresthesia

- Pain

- Tenderness to palpation

Common to Le Fort II:

- Midface deformity and edema

- Combined mobility of maxilla and nose

- Nasofrontal suture step deformity

- Widening of intercanthal space

- Bilateral periorbital edema, periorbital ecchymosis, and cerebrospinal rhinorrhea or otorhea, indicating basal skull fracture

- Bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhage, mostly spanning to the medial portion of the eye

- Unilateral or bilateral epistaxis

- Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea

- Maxillary paresthesia

- Pain

- Tenderness to palpation

- Crepitus upon palpation of orbital rims

Common to Le Fort III:

- Gross facial edema

- Lengthening and flattening of the face

- Orbital hooding

- bilateral periorbital edema and ecchymosis (Raccoon eyes), cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea/otorrhea, hemotympanum, and retroauricular ecchymosis (Battle’s sign), suggesting signs of basal skull fracture

- Bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhage, mostly spanning the entire eye

- Ocular abnormalities including diplopia, enophthalmos, traumatic telecanthus, and transient vision impairment

- Minimal sensory changes

- Signs of elevated intracranial pressure

Clinical diagnosis[5][6][9][11][12][13]

Clinical diagnosis of Le Fort fractures I, II, and III are determined based on the extent of maxillofacial mobility. To diagnose a Le Fort fracture of any type, there must be fractural involvement of the pterygoid processes. While all Le Fort fractures are characterized by pterygoid process fractures, there are some unique features that help differentiate between the three types of Le Fort fractures:

- Le Fort I fractures are low transverse maxillary fractures with mobility limited to the maxilla. Le Fort I fractures are the only class to involve a fracture of the anterolateral margin of the nasal fossa.

- Le Fort II fractures are pyramidal fractures leading to mobility of the maxilla and nasal bones. An exclusive feature of a Le Fort II fracture is the involvement of an inferior orbital rim fracture.

- Le Fort III fractures are craniofacial disjunction fractures which result in mobility of the maxilla, nasal bone, and zygomas. Le Fort III fractures are characterized by fractures in the pterygoid process and zygomatic arch. This fracture is the most severe form of maxillofacial injury and is considered a true craniofacial disjunction of the midface from the cranium.

Diagnostic procedures[5][6][9][11][12][13]

Proper imaging is required for adequate evaluation of fracture patterns and for preoperative planning. While some literature proposes that conventional plain film X-rays may be utilized in isolated nasal bone or lateral midface fractures, they serve a limited role in clinical practice. High-resolution multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) with multiplanar reformations (MPR) is considered the best imaging modality for evaluation of acute and non-acute facial fractures. Three-dimensional (3-D) processing is valuable for assessment of complex facial deformities and allows for accurate preoperative preparation to ensure the best cosmetic outcome. It’s important to conduct a thorough history and physical to evaluate for additional injuries beyond maxillofacial fractures. CT imaging of the head rather than maxillofacial should be obtained to evaluate for intracranial pathology. Additionally, injuries of the midface are frequency associated with C5-C7 disruption and thus a CT cervical spine should be obtained as well. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is generally reserved for cases of facial nerve injury not explained by CT or for evaluation of intracranial injuries prior to surgical intervention. Postoperative radiography is generally not recommended unless there is concern for post-operative infection or need for additional surgery. While radiation is generally avoided in children if possible, radiographic imaging with CT scan is typically necessary for the accurate characterization and preoperative planning of facial fractures.

The three Le Fort fracture patterns are characterized by fractural involvement of the pterygoid processes. It should be noted that pterygoid involvement is a sensitive finding rather than specific, and does not guarantee a Le Fort fracture.

A comprehensive CT examination and diagnostic angiography of the head should be considered to rule out deep trauma to the brain and surrounding major vascular structures.

Radiographic Exams:

- Fine-cut (1-3 mm sections) non-contrast 2-D CT imaging; gold standard and is required for diagnosis

- 3-D CT imaging for surgical treatment planning

- MDCT (Multidetector computed tomography)

- Plain Films (Water’s view); limited value - replaced by CT scans

- Panoramic radiographs for associated mandibular fractures

- MRI for soft-tissue trauma, including orbital MRI for optic nerve edema or hematoma, ocular muscle disorders, intraocular disorders, and displaced foreign bodies

Differential diagnosis

The list of differential diagnosis includes:

- Acute subdermal hematoma

- Frontal fracture

- Zygomatic arch fracture

- Zygomaticomaxillary fracture

- Nasoorbitoethmoidal fracture

- Internal orbital fractures (i.e. orbital floor and/or medial wall fractures)

- Optic canal fractures

Management

General treatment[6][7][9][14][15][16]

Following the initial evaluation and the completion of the primary and secondary surveys, appropriate consultations should be made to include all relevant specialists on the management team (e.g., ophthalmologists, otolaryngologists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, neurosurgeons, plastic surgeons). This is particularly important in cases of severe trauma in order to ensure that the treatment plan is comprehensive and to avoid poor outcomes. In emergency situations, such as airway compromise, cervical spine injury, traumatic brain injury, vision-threatening injuries, or uncontrolled bleeding, immediate surgical interventions may be necessary. Definitive surgery can be performed after potentially life-threatening injuries are addressed and the patient is stabilized.

The timing of surgery depends on the urgency and severity of each case. In non-emergent situations, such as in a stable patient with facial fractures only, surgical intervention is often delayed until facial swelling has diminished, typically 5-7 days after injury. Ideally, surgical intervention should take place no more than 14 days after the initial injury in order to promote better healing of the hard and soft tissues.

The primary goals of Le Fort fracture management are to:

- Re-establish pre-traumatic occlusal relationships

- Restore the facial height and projection

- Restore integrity of the maxillary horizontal and vertical buttresses (i.e., Le Fort I, II, and III), as well as the nose and the orbit (i.e., Le Fort II and III)

Key factors to always consider while repairing Le Fort fractures also include:

- Maintaining a patent airway and appropriate selection of intubation technique, if indicated. Nasotracheal intubation is contraindicated in patients with suspicion of skull base fracture and midface instability.

- Evaluating potential concomitant cervical spine injury

- Hemostasis of active bleeding or epistaxis, if present

- Management of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea or brain injury, if present

Medical therapy[9][15]

While still a controversial topic, antibiotic prophylaxis is often initiated by many surgeons in the management of Le Fort fractures due to maxillofacial injuries being generally considered as contaminated because of the communication of the fractures with the oral cavity, nose, and/or sinuses. Some practitioners opt for a more conservative approach, advocating to only prescribe antibiotics prophylactically in patients with CSF rhinorrhea and only after consultation with a neurosurgeon.

Following surgery, antibiotics are typically prescribed for 5-7 days for coverage. Patients with Le Fort fractures are treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics in order to cover both sinus and oral pathogens. Intravenous penicillin or ceftriaxone are preferred by most surgeons; however, cephalosporins and clindamycin are also frequently used. Analgesics are also prescribed for the treatment of pain but are discontinued after the pain subsides.

Surgery[5][6][7][9][14][15][17]

There are two types of treatment for midface fractures – open and closed reduction.

Open Method (most commonly used today)

This method involves surgical reduction of the midface fractures by exposing the fracture site.

- Plate osteosynthesis

- Wire osteosynthesis

Closed Method (less preferred in contemporary practice)

This method is noninvasive and reduces the fracture segments without exposing the fracture site.

- Internal skeletal suspension

- External fixation methods

In today’s practice, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is considered the gold standard for the treatment of Le Fort fractures because ORIF provides sufficient access to the fracture sites for stable fixation and adequate repositioning of the fracture segments, resulting in a better functional and esthetic outcome.

Maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) is a type of rigid fixation that is used to stabilize occlusion between the maxilla and the mandible and is indicated for most Le Fort fractures. Arch bars are the type of MMF used by the majority of surgeons.

The most common method of internal fixation is plating. Generally, 1.5-2.0 mm L-shaped, X-shaped, or Y-shaped plates are used for the fixation of the buttresses and the approximation of fracture segments to their pre-injury locations. Plating should be secured adequately to thick bone while also prioritizing the placing of the plates in the same direction as the forces of mastication. It is recommended that there are at least 2 screws on each side of the fracture, and monocortical, self-tapping screws are considered the most ideal. In instances of >5mm gaps between the fracture segments, it is advisable to repair the area with bone grafting in addition to the bridging plates and screws.

Incisions are carefully planned prior to surgery in order to minimize scarring and to maximize the esthetic result. The following types of incisions are used frequently in Le Fort fractures for different indications:

- Intraorally via Oral Vestibular incision

- Periocular via the Subciliary (Lower Lid Transcutaneous), Lower Lid Transconjunctival, Combined Transconjunctival and Lateral Canthotomy, or Upper Eyelid incision

- Brow incision

- Coronal incision

- Through existing lacerations

The following subsections include specific surgical techniques and treatments for each of the 3 types of Le Fort fractures.

Le Fort I

For Le Fort I fractures that are minimally displaced or undisplaced, the fractures can be reduced and stabilized sufficiently with MMF only.

In instances when there is mobility or displacement of the maxilla (i.e., disimpaction), ORIF is usually required via an oral vestibular incisional approach. The zygomaticomaxillary and nasomaxillary buttresses on each side are plated in the same direction of the forces of mastication. The occlusion is then aligned to approximate the pre-injury state by MMF (arch bars and intermaxillary fixation) for 6 weeks. Following the release of MMF, guiding elastics are placed.

If the Le Fort I fracture is impacted, maxillary disimpaction can be performed manually or with disimpaction forceps.

Le Fort II

Almost all Le Fort II fractures require ORIF for sufficient repair. Similar to the Le Fort I fracture, sublabial vestibular incisions are made for visualization of the maxillary fractures. Le Fort II fractures also require additional exposure of the orbital rim, typically by the transconjunctival incision, to repair the orbital floor fracture. It is critically important to ensure that the midface is not impacted and rotated superiorly before any rigid fixation in order to prevent malunion or an anterior open bite. After the fracture is disimpacted, the occlusion is restored with MMF. Next, the zygomaticomaxillary buttresses are secured by fixation with plating, followed by the frontonasal suture and inferior orbital rim. Following the release of MMF after 6 weeks, guiding elastics are placed.

Note: concomitant fractures are treated in sequence: Le Fort I, then II, then III.

Le Fort III

For Le Fort III fractures, there are many cases that involve airway compromise that require intubation. In some situations, a tracheostomy or submental intubation may be indicated. Nasotracheal intubation is contraindicated due to the nasal component of fractures and high risk of accidental intracranial intubation.

The first step of treatment is to disimpact the maxilla, followed by re-orientation of the occlusion by MMF. Next, through a coronal incisional approach in most cases, the zygomaticofrontal sutures are plated bilaterally. If necessary, the nasofrontal suture, the naso-orbitoethmoid (NOE) complexes, and nasomaxillary buttresses are plated as well. Following the release of MMF after 6 weeks, guiding elastics are placed.

Surgical follow up[6][17]

- Follow-up is determined by the severity of the fracture, procedure performed, expected healing time, and the duration of MMF

- Globe and vision should be checked in any orbital involving injuries or procedures

- Antibiotics and analgesics are prescribed as indicated

- Most Le Fort fracture patients remain in the hospital an average of 9 days for treatment and recovery

- Oral hygiene must be reinforced and addressed with the patient

- Chlorhexidine oral rinses three times daily during MMF

- MMF should be cleaned using pulsed irrigation or with a soft tipped bristle brush

- Monitor closely for malunion, infection, or bleeding

- Monitor body temperature and pulse for signs of fever or infection

- Patient should be advised of strict liquid diet followed by a semi-solid diet for 6 weeks

- Adequate fluid intake to maintain a proper electrolyte balance

- Adequate calories and high protein diet

- Sutures should be removed after 5-7 days

Complications[5][18][19]

Ophthalmic Complications

Globe complications are more common with Le Fort II and III type fractures. Complications depend on the number of orbital walls that are involved. Permanent visual disability is more likely with increased numbers of damaged orbital walls.

- Diplopia from extraocular muscle entrapment or paresis

- Open globe injuries - rupture or avulsions

- Optic nerve concussion or compression

- Lid malposition such as ptosis, lagophthalmos, acquired epiblepharon or lower eyelid retraction

- Globe malposition, such as enophthalmos, exophthalmos, and hypoglobus

- Telecanthus

- Lacrimal sac or nasolacrimal duct injury

- Orbital hematoma and orbital compartment syndrome

- Complications from concurrent globe contusion

- Retinal and choroidal injuries

- Hyphema, lens subluxation, secondary Glaucoma

- Traumatic optic neuropathy

Other complications

- Facial deformities

- Horizontal widening and midface depression

- Reduced midfacial height and projection

- Malunion

- Malocclusion

- Anterior open bite

- Impaired mastication

- Diminished or lost nerve function (from primary insult or secondary to surgical repair) from:

- Facial nerve injury

- Trigeminal nerve (V2), superior alveolar nerve or infraorbital nerve injury

- Chronic sinusitis or mucocele

- Infection

- Osteomyelitis

- Injury to tooth roots from screws during plating of maxilla

Prognosis[6][7][9]

Treatment outcome is dependent on the mechanism of injury, presence of associated injuries, and the location and severity of injury. The mortality rate for Le Fort fracture has been found to be higher than simple midface fractures; Le Fort fractures have a mortality rate of 11.6%, whereas simple midface fractures have a 5.1% rate. Additionally, the mortality of Le Fort I, II and III fractures are progressive with increased severity - Le Fort I fractures have the lowest mortality rate (~0%) and Le Fort III have the highest (8.7%).

Le Fort fractures are also associated with considerable morbidity, especially with respect to the development of visual problems (47%) and diplopia (21%). Difficulty with mastication (40%) and difficulty breathing (31%) are also common complaints among Le Fort fracture patients.

Interestingly, in a recent 2017 review article, Phillips and Turco found that factors such as body mass index (BMI), implant type, presence of multiple fractures, and smoking history had no impact on the rates of postoperative infection following the repair of Le Fort fractures. However, the authors found that Le Fort I fractures had the highest risk of infection due to the repair requiring ORIF through an intraoral approach (i.e., Le Fort II and III injuries may not require an oral vestibular incision).

Most patients have satisfactory outcomes for aesthetics and function (89.1%); however, approximately 10.9% of Le Fort fracture patients have been found to have persistent challenges, facial deformity, or infection.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Patel BC, Wright T, Waseem M. Le Fort Fractures. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed February 13, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526060/

- ↑ Arslan ED, Solakoglu AG, Komut E, Kavalci C, Yilmaz F, Karakilic E, Durdu T, Sonmez M. Assessment of maxillofacial trauma in emergency department. World J Emerg Surg. 2014 Jan 31;9(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-9-13. PMID: 24484727; PMCID: PMC3912899.

- ↑ Gassner R, Tuli T, Hächl O, Rudisch A, Ulmer H. Cranio-maxillofacial trauma: a 10 year review of 9,543 cases with 21,067 injuries. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003 Feb;31(1):51-61. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(02)00168-3. PMID: 12553928.

- ↑ Lucke-Wold B, Pierre K, Aghili-Mehrizi S, Murad GJA. Facial Fractures: Independent Prediction of Neurosurgical Intervention. Asian J Neurosurg. 2021 Dec 18;16(4):792-796. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_251_21. PMID: 35071079; PMCID: PMC8751529.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 Frakes MA, Evans T. Evaluation and management of the patient with LeFort facial fractures. J Trauma Nurs. 2004;11(3):95-101; quiz 102. doi:10.1097/00043860-200411030-00002

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 Servat JJ, Black EH, Nesi FA, Gladstone GJ, Calvano CJ. Smith and Nesi’s Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Chapter 15 Pg 283-288. Springer International Publishing : Imprint: Springer; 2021. Accessed February 13, 2022. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-41720-8

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Phillips BJ, Turco LM. Le Fort Fractures: A Collective Review. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2017;5(4):221-230. doi:10.18869/acadpub.beat.5.4.499.

- ↑ Patil RS, Kale TP, Kotrashetti SM, Baliga SD, Prabhu N, Issrani R. Assessment of changing patterns of Le fort fracture lines using computed tomography scan: an observational study. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 2014;72(8):984-988. doi:10.3109/00016357.2014.933252

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 Patel BC, Wright T, Waseem M. Le Fort Fractures. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed February 13, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526060/

- ↑ Mahoney N. Le Fort Fractures - American Academy of Ophthalmology. Accessed February 13, 2022. https://www.aao.org/oculoplastics-center/le-fort-fractures

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Homsi N. Examination of patients with midfacial injuries. Accessed February 13, 2022. https://surgeryreference.aofoundation.org/cmf/trauma/midface/further-reading/examination-of-patients-with-midfacial-injuries

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Ceallaigh PÓ, Ekanaykaee K, Beirne CJ, Patton DW. Diagnosis and management of common maxillofacial injuries in the emergency department. Part 4: orbital floor and midface fractures. Emergency Medicine Journal : EMJ. 2007;24(4):292. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/emj.2006.035964

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 How to Simplify the CT Diagnosis of Le Fort Fractures : American Journal of Roentgenology : Vol. 184, No. 5 (AJR). Accessed February 13, 2022. https://www.ajronline.org/doi/10.2214/ajr.184.5.01841700

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Kim HS, Kim SE, Lee HT. Management of Le Fort I fracture. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18(1):5-8. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.5

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 15.2 Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, et al., eds. Cummings Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 7th ed. pg. 292-293, 295-298, 303-310. Elsevier; 2020.

- ↑ Singh AK, Sharma NK. Maxillofacial Trauma: A Clinical Guide.; 2021. Chapter 15: Le Fort Fractures by Gina M. Rogers and Richard C. Allen, pg. 283-295.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Singh AK, Sharma NK. Maxillofacial Trauma: A Clinical Guide.; 2021. Chapter 16 Le Fort Fractures by Naresh Kumar Sharma and Nitesh Mishra, pg. 271-292.

- ↑ Nagase DY, Courtemanche DJ, Peters DA. Facial fractures – association with ocular injuries: A 13-year review of one practice in a tertiary care centre. Can J Plast Surg. 2006;14(3):167-171.

- ↑ Orbital cellulitis: a rare complication after orbital blowout fracture - PubMed. Accessed February 14, 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16157384/