Landolt Ring–Shaped Epithelial Keratopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Landolt Ring–Shaped Epithelial Keratopathy

Disease Entity

Landolt ring–shaped epithelial keratopathy describes a condition in which focal lesions in the basal layer of the corneal epithelium that resemble a Landolt ring, or the letter “C” develop insidiously. There are eleven known cases first published in a case study in 2015[1]

Disease

Landolt Ring–Shaped Epithelial Keratopathy

Etiology

At present, the Landolt ring-shaped epithelial keratopathy is a sporadic and chronic process. It is hypothesized that weather affects the disease as lesions tend to develop in the winter months (i.e., all cases were diagnosed between November and March). Age may also play a role as 64% of cases have occurred in patients 41-52 years old. Finally, a genetic factor may also contribute as all published cases have been reported in Japanese individuals that are not related and came from different parts of the country[1].

Risk Factors

There are no known risk factors.

General Pathology

Pathophysiology

While the pathophysiology is still unknown, some ocular changes give a clue for the underlying pathology. In vivo confocal microscopy of the corneal epithelium shows differing morphologic characteristics in the superficial cell layer, wing cell layer, and basal cell layer of the cornea. In a case report, the anterior superficial layer displayed cellular ballooning with hyporeflective cytoplasmic changes. Conversely, wing cells showed hyperreflective nuclear and cell membrane changes. The deep basal cell layer contains the Landolt shaped-ring structures and abnormal hyperreflective precipitates[1]. The bowman layer (including subbasal nerve plexus and long nerve fibers), stromal layer, and endothelial layer were intact. Additionally, on slit lamp exam, the anterior chamber was unremarkable. Superficial ballooning and swelling also contributed to disruption of the epithelial junction, as seen on fluorescein staining[1].

This disease is likely not limited to Japanese individuals and may be seen in other ethnicities. It has been proposed that the pathology may be associated with regional limbal stem cell dysfunction in a few clock hours, and reduced cell turnover in the area corresponding to the lesions may be the cause of the characteristic lesions. This idea of limbal cell dysfunction is supported by Thoft and Friend’s X,Y,Z hypothesis of corneal regeneration. This theory proposes that centripetal regeneration of epithelium from the limbus and proliferation of basal epithelial cells maintain epithelium from cells lost at the surface[2]. Though, it should be noted that further work is needed to understand the underlying pathophysiology of this process fully.

Primary Prevention

There are no known preventative measures

Diagnosis

History

Patients most often complain of insidious bilateral foreign-body sensation, photophobia, ocular pain, or blurred vision; one patient reported increased glare. Symptoms became clinical in the winter months, especially around changes in the weather (e.g., 90% of patients became clinical in either December or March). Prior history of similar symptoms may also be present, as all patients who were followed for at least a year had recurrence of their symptoms[1].

Physical Examination

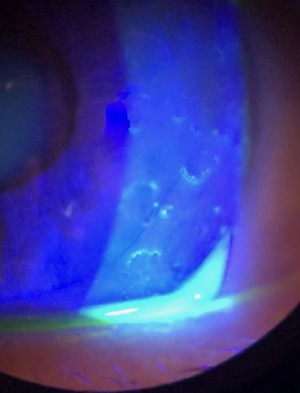

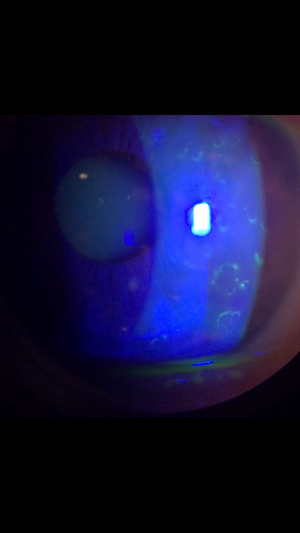

Slit lamp exam shows randomly dispersed Landolt-shaped rings in the corneal epithelium, which can be enhanced with fluorescein staining. Figure 1 is a slit lamp photo of a patient with Landolt ring-shaped lesions. The shape (i.e., the location of the gap in the “C”), number, and size of the ring lesions varied from patient to patient and from visit to visit, eventually resolving with disease remission. Vesicular changes can be seen, but there is no apparent inflammation. Some of the patients demonstrated a “fractal pattern” wherein smaller lesions were grouped to form a larger Landolt ring. No decrease in corneal sensation was observed in tested patients, and fundoscopy was unremarkable. Intraocular pressure was normal for all patients[1].

Symptoms

As noted above, the most common symptoms are the sensation of a foreign body and photophobia. Ocular pain and blurred vision are often reported as well[1].

Clinical diagnosis

Diagnostic procedures

There are no established diagnostic criteria, and Landolt ring-shaped epithelial keratopathy is a clinical diagnosis. This relatively unstudied corneal disease seems to have been observed by other clinicians, including the principle author, though there are no other published reports. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients with characteristic lesions in the basal layer of the corneal epithelium. Clinical suspicion may be higher in patients of Japanese ancestry, or during changes in winter weather, though this has not been proven to be statistically significant.

Laboratory test

There are no laboratory tests available for Landolt ring-shaped epithelial keratopathy.

Differential diagnosis

Landolt ring-shaped epithelial keratopathy should be differentiated from other pathologies that can affect the corneal epithelium. These include, but are not limited to trauma[3][4], medications[5][6], infection[7][8], and other corneal epithelial disorders.

Management

General treatment

Treatment for Landolt ring-shaped epithelial keratopathy is comprised of various topical options. However, there is no proven benefit to any specific therapy. Additionally, the disease is self-limiting and two cases of untreated patients reported remission at three weeks and four months respectively. Common approaches to medical management include corticosteroids, antimicrobials, anti-allergics, and artificial tears. One patient was treated with immunosuppressive cyclosporine and another with ganciclovir 0.5%. Regardless of the treatment received, all patients healed with no decrease in visual acuity or reports of foreign body sensation or ocular pain at their final visit. From the published cases, there are no clear factors that shorten the clinical course[1].

Due to the recurrent nature of the disease, corneal insults, and length of symptoms, testing for viral causes may be beneficial. Of the available cases, six of the eleven cases (55%) underwent corneal scraping and polymerase chain reaction for human herpesvirus serotypes 1-8 which all came back negative. Additionally, of note, all but one case (91%) were bilateral, which is less likely to occur in viral ocular pathologies.

In terms of a potential treatment, realizing that this may be secondary to a regional limbal cell dysfunction, corneal scraping, amniotic membrance transplant and bandage soft contact lens may be beneficial[9][10]. Additionally, interferon-alpha 2b with topical retinoic acid (0.01%) has had positive effects in patients with partial limbal stem cell deficiency[11].

Medical follow up

Medical follow up is recommended because patients who were followed for more than a year developed recurrence of their symptoms[1]. Based on the reported chronologic appearance of symptoms, follow up may best be done after changes in the winter season.

Surgery

The disease is self-limiting and reported recurrences have not led to complications or permanent visual acuity impairment requiring corneal surgery.

Prognosis

Patient prognosis is good; all known cases resolved with or without medical therapy within six months (mean time to resolution was reported at 3.0 months). However, resolution may be followed by recurrences requiring follow-up care.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Inoue T, Maeda N, Zheng X, et al. Landolt Ring-Shaped Epithelial Keratopathy: A Novel Clinical Entity of the Cornea. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.2381

- ↑ Thoft RA, Friend J. The X, Y, Z hypothesis of corneal epithelial maintenance. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1983.

- ↑ Reid GA, Musa F. OCT imaging of a traumatic endothelial ring. Cornea. 2014. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000000193

- ↑ Cibis GW, Weingeist TA, Krachmer JH. Traumatic Corneal Endothelial Rings. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978. doi:10.1001/archopht.1978.03910050261014

- ↑ Mergen B, Ozdamar A, Sarici AM. Ring Keratitis From Topical Anesthetic Abuse After Laser Epithelial Keratomileusis. Eye Contact Lens. 2018. doi:10.1097/ICL.0000000000000433

- ↑ Raizman MB, Hamrah P, Holland EJ, et al. Drug-induced corneal epithelial changes. Surv Ophthalmol. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.11.008

- ↑ Van Horn DL, Davis SD, Hyndiuk RA, Alpren TVP. Pathogenesis of experimental Pseudomonas keratitis in the guinea pig: Bacteriologic, clinical, and microscopic observations. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1978.

- ↑ Lobo AM, Agelidis AM, Shukla D. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex keratitis: The host cell response and ocular surface sequelae to infection and inflammation. Ocul Surf. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2018.10.002

- ↑ Grüterich M, Tseng SCG. Surgical approaches for limbal stem cell deficiency. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2002. doi:10.1055/s-2002-32637

- ↑ Anderson DF, Ellies P, Pires RTF, Tseng SCG. Amniotic membrane transplantation for partial limbal stem cell deficiency. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001. doi:10.1136/bjo.85.5.567

- ↑ Tan JCK, Tat LT, Coroneo MT. Treatment of partial limbal stem cell deficiency with topical interferon α-2b and retinoic acid. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307411