Lacrimal Gland Prolapse (Dislocation)

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Lacrimal gland prolapse is recognized by the following codes as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) nomenclature:

ICD-9

- ICD 9 Data

- 375.16 Dislocation of lacrimal gland

ICD-10

- ICD 10 Data

- HO4.161 Lacrimal gland dislocation, right lacrimal gland

- H04.162 Lacrimal gland dislocation, left lacrimal gland

- H04.163 Lacrimal gland dislocation, bilateral lacrimal glands

- H04.169 Lacrimal gland dislocation, unspecified lacrimal gland

Disease

Lacrimal gland prolapse, otherwise known as lacrimal gland displacement, dislocation, or herniation, refers to a bulging of the lacrimal gland into the outer upper eyelid that can be an isolated condition associated with aging or trauma, or associated with various congenital, infectious, inflammatory, or auto-immune disorders. When occuring in isolation, the condition is generally benign, but patients may be concerned with the appearance as it may lead to fullness in the temporal region of the upper eyelid. Of note, lacrimal gland prolapse is a term typically used to describe a benign malposition of the lacrimal gland. However, lacrimal gland malposition may also indicate a malignant process and this should therefore be considered when evaluating patients.

History

The first case of bilateral lacrimal gland prolapse was discussed in 1895 by Russian ophthalmologist S.S. Golovin.[1] Prior to that, lacrimal gland prolapse was considered to be a manifestation of blepharochalasis, a rare condition characterized by episodic edema and inflammation of the upper eyelid. Golovin was the first to consider lacrimal gland prolapse a distinct entity, though many in the U.S. continued to consider prolapse of the lacrimal gland as a secondary finding. It wasn’t until 1933 that the ophthalmologist James W. Smith published a literature review in JAMA concluding that spontaneous lacrimal gland is a separate disease entity distinct from blepharochalasis.[2]

Anatomy

The lacrimal gland sits within the lacrimal fossa of the frontal bone, bordered superiorly by the frontal bone and inferiorly by the globe of the eye. It is composed of two lobes, the larger orbital lobe and smaller palpebral lobe, which are incompletely separated by the lateral horn of the levator aponeurosis.[3] The palpebral lobe contains two to five ducts, which bring tear fluid from the gland to the surface of the eye. Two other accessory lacrimal glands, otherwise known as the glands of Krause and the glands of Wolfring (or Ciaccio) are located in the palpebral conjunctiva and together with the main lacrimal gland compose the secretory complex that produces tear fluid.[4]

Epidemiology

Lacrimal gland prolapse has been found to be present in 15% of patients undergoing upper blepharoplasty based on clinical presentation.[5][6][7] That number is likely even higher among the older population based on intraoperative identification, as clinical presentation of lacrimal gland prolapse can be masked by concomitant eyelid changes with age. In one study evaluating 57 patients presenting for upper blepharoplasty in whom the mean age was 78, 34 patients (60%) had some degree of lacrimal gland prolapse found intraoperatively.[8]

The etiologies of lacrimal gland prolapse include involutional changes associated with aging, post-infection or post-traumatic, as well as congenital ptosis, craniofacial deformities, thyroid eye disease, and blepharochalasis (Table 1).[8][9] The epidemiology of lacrimal gland prolapse is poorly studied, but when associated with blepharochalasis, it is more common among younger patients, while lacrimal gland prolapse associated with other involutional changes is more common in older patients. When lacrimal gland prolapse does occur, subconjunctival prolapse of the smaller palpebral lobe is more common than prolapse of the orbital lobe posterior to the orbital septum, though both can occur simultaneously. Prolapse of the orbital lobe of the lacrimal gland is more commonly associated with blepharochalasis and is more likely to occur bilaterally, giving the upper eyelids a look of temporal fullness (Figure 1).[3]

| Table 1: Conditions associated with lacrimal gland prolapse[6][10][11][12] |

|---|

Involutional changes

|

Inflammatory

|

Infectious and post-infectious

|

| Post-traumatic |

| Congenital ptosis or craniofacial deformities |

Autoimmune

|

| Orbital tumor |

Miscellaneous

|

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of lacrimal gland prolapse depends on the etiology of the prolapse, but most commonly occurs due to weakening of the supportive structures of the eye secondary to aging or inflammation, or due to increased intraorbital pressure. In aging, lacrimal gland prolapse occurs due to degeneration of the supportive structures of the globe, leading to increased skin laxity, atrophy or hypertrophy of the orbicularis muscle, weakness of the orbital septum, and relaxation of the suspensory ligaments that support the lacrimal gland. This can result in prolapse of intraorbital fat as well as either one or both lobes of the lacrimal gland.[7]

The pathophysiology of lacrimal gland prolapse associated with blepharochalasis is similar to that seen with aging, and involves thinning of the epithelium and loss of elastic tissue. Blepharochalasis is a condition seen most commonly around puberty and is characterized by episodic edema of the eyelids, usually bilateral, that can lead to eyelid ptosis (Figure 2).[13] It is unclear whether blepharochalasis represents a localized form of angioedema or a separate disorder of its own,[14] but the edema can result in either excess or atrophic eyelid skin, as well as laxity of the canthal tendons that can lead to prolapse of the lacrimal gland.[15]

Lacrimal gland prolapse can also result from increased intraorbital pressure, as can be seen secondary to trauma, thyroid eye disease, ocular neoplasms, and infection. In thyroid eye disease, lymphocytic and plasmacytic infiltration of the extraocular tissues leads to fibroblast activation and the subsequent production of acid mucopolysaccharides that can affect not only the extraocular muscles, but the lacrimal gland as well.[16] Edema of the lacrimal gland can result in lacrimal gland enlargement and anterior displacement due to increase intraorbital pressure.[17][18] Lacrimal gland prolapse can also result from congenital ptosis or craniofacial deformities due to both increased posterior pressure from decreased orbital volume, as well as weakened supportive structures.6 Rarely, lacrimal gland prolapse can occur from increased intraorbital pressure secondary to trauma, which occurs most commonly in children due to less developed upper and lateral orbital margins.[19][20]

Diagnosis

History

Most cases of lacrimal gland prolapse, especially those associated with aging, are asymptomatic. When symptomatic, patients may complain of eyelid hooding, temporal eyelid fullness, or visual field deficit (Table 2).

| Table 2: Symptoms of lacrimal gland prolapse [8][21] |

|---|

| Fullness in the temporal quadrant of the upper eyelid |

| Temporal ptosis |

| Eyelid hooding |

| Visual field deficit |

| Periorbital edema |

| Increased pressure on the globe that can lead to discomfort |

Physical Examination

Examination of patients presenting with possible lacrimal gland prolapse is primarily done via inspection for lateral eyelid bulging and palpation of the upper eyelid. Upper eyelid eversion can also be performed to better visualize the palpebral lobe of the lacrimal gland. Hertel exophthalmometry readings, as well as a full eye exam, including vision, pupillary exam, extraocular motility, and visual fields are important to rule out an orbital process. The eyelid skin should be examined for color/erythema, firmness, and skin characteristic (e.g. crepe-like skin can be seen in blepharochalasis or floppy eyelid syndrome). On physical exam, isolated lacrimal gland prolapse associated with aging can be difficult to detect clinically due to concomitant involutional changes including brow ptosis and dermatochalasis.[8]

Signs

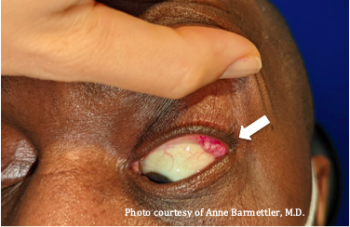

Prolapse of the palpebral lobe of the lacrimal gland may be seen upon eversion of the upper eyelid, revealing a pink or grey bulging mass in the lateral part of the palpebral conjunctiva (Figure 3). When the orbital lobes prolapse, it may present as a bulging or fullness of the temporal region of the upper eyelids, often bilaterally. This may look like temporal ptosis or an S-shaped lid, presenting as a baggy upper eyelid that sometimes hangs over the eyelashes and obliterates the lid fold (Figure 1).[3] The examiner can palpate such a bulge between his or her index finger and thumb, and notice that it is slightly lobulated and firmer than the surrounding intraorbital fat. With gentle pressure, the prolapsed lacrimal gland is often reducible into the lacrimal fossa. Retropulsion of the globe can also exaggerate the prolapse.[7]

Lateral eyelid fullness, while often seen in patients with lacrimal gland prolapse, has been found in one study to have a low positive predictive value (30%) and a high negative predictive value (96%) for lacrimal gland prolapse, meaning patients who present with lateral eyelid fullness often do not have lacrimal gland prolapse but rather other involutional changes like dermatochalasis or eyebrow ptosis. Another test with a higher positive predictive value that has been described is the Supine Test, which involves asking the patient to lay supine and look down while the examiner pulls up on the eyebrow, at which point any remaining bulge in the lateral upper eyelid is presumed to be a lacrimal gland prolapse.[22]

Clinical Diagnosis

Lacrimal gland prolapse is usually a clinical diagnosis, generally made by history and physical exam, though it can be a difficult diagnosis to make as it can be mistaken for other conditions including prolapsed intraorbital fat, dermolipoma, or lacrimal gland malignancy (see differential diagnosis). Mild lacrimal gland prolapse can also be clinically silent and asymptomatic.

Ancillary Tests

Imaging

In cases of unknown etiology, MRI can be utilized to characterize the lacrimal gland enlargement. Ultrasound of the eye has been used to aid in the diagnosis of lacrimal gland tumors, as well as cysts and inflammation and can offer information related to the position of the lacrimal gland; however, this is not frequently utilized in the diagnosis of lacrimal gland prolapse.[7]

Biopsy

Tissue biopsy can be considered to distinguish prolapsed lacrimal gland tissue from inflammatory or malignant processes.[13][19] Biopsy should be done from the orbital lobe to avoid damage to the ducts, which bring the tears from the gland to the surface of the eye. In cases in which lymphoma should be ruled out, a specimen, about the size of a pencil eraser, should not be sent in formalin, but be sent fresh to pathology for flow cytometry.

Laboratory Testing

Laboratory testing can be done when there is a suspected secondary etiology for the prolapsed lacrimal gland. This can include thyroid function tests for suspected thyroid eye disease or an urticarial screen and C1 esterase inhibitor level when considering blepharochalasis.[13] Other tests commonly ordered for patients with bilateral lacrimal gland disease include an Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) level, lysozyme, complete blood count, an anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) level, and IgG4 (see Table 3). In patients with primary lacrimal gland prolapse, there are usually no laboratory abnormalities.[23]

| Table 3: Ancillary investigations performed in patients with lacrimal gland prolapse |

|---|

Ocular imaging evaluation

|

Hematology and biochemistry

|

Serology

|

Serum

|

Pathology

|

Differential Diagnosis

Lacrimal gland prolapse must be distinguished from other conditions, including prolapsed orbital fat (see Figure 4), lipodermoid (whiter in color, may contain hairs), dermatochalasis, eyebrow ptosis, lacrimal gland tumors, including both epithelial and non-epithelial tumors, and ectopic lacrimal gland tissue.[4] Ectopic lacrimal gland tissue presents a unique challenge, as such tissue is often present at the temporal epibulbar conjunctiva and can be difficult to distinguish from native lacrimal gland tissue.[4][19] Other differentials for upper eyelid masses include dacryoadenitis, lacrimal gland ductal cysts, foreign body granulomas, lymphoma, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Sjögren's syndrome, idiopathic orbital inflammation, and IgG-related ophthalmic disease.[23][24][25]

Disease Monitoring

When associated with blepharochalasis, it is common to monitor disease progression and wait until the disease is quiescent for 6 to 12 months before attempting surgical repair of lacrimal gland prolapse, as repeated edematous attacks can lead to recurrence of associated eyelid ptosis and gland prolapse.[13][15][26]

Management

Surgery

Lacrimal gland prolapse is managed surgically during upper blepharoplasty typically for cosmetic reasons and to relieve possible mass effect or visual field defect. The prolapsed lacrimal gland can be resuspended via suture suspension of the gland to the orbital rim periosteum within the lacrimal gland fossa. Resection of the prolapsed gland is not recommended, as it can lead to chronic dry eyes secondary to aqueous tear deficiency and loss of ocular lubrication.[13]

Various techniques have been proposed for suture suspension of the prolapsed lacrimal gland. One technique involves suturing either the anterior or inferior portion of the gland capsule to the inside of the superotemporal orbital rim to avoid damage to the glandular tissue itself.[19][21] Two to three sutures with nonabsorbable 4-0, 5-0, or 6-0 monofilament nylon or prolene sutures, or absorbable chromic or PDS sutures, have been used for this in either an interrupted or mattress fashion. Another technique is to suture Whitnall’s ligament over the gland to the superior orbital rim to act as a sling that prevents anterior displacement of the gland.[7] This technique has been proposed as superior to the first, as it may be associated with fewer cases of cyst formation, though it has not been widely adopted. In milder presentations, characterized by less than 4mm of prolapse, light cautery to the gland capsule and surrounding soft tissue has also been utilized to reposition the prolapsed lacrimal gland, but this may be associated with a higher recurrence rate.[8]

Lacrimal gland prolapse can present a surgical challenge during upper blepharoplasty, as the prolapsed gland can resemble intraorbital fat, a dermolipoma, or a neoplasm.[4] Care should be taken not to excise lacrimal gland tissue and inadvertently cause dry eye. In cases in which lacrimal gland changes are suspected, one can take a biopsy of the prolapsed gland to rule out other neoplastic or inflammatory processes prior to resuspension. Because the lacrimal gland is highly vascular, it is important to maintain good homeostasis prior to wound closure to prevent hematoma formation.[13]

Complications and Follow Up

The most commonly cited post-surgical complaints following upper blepharoplasty with lacrimal gland repositioning include prolonged upper eyelid swelling, temporal eyelid pain, and dry eye symptoms. In one study evaluating 40 patients, who had undergone blepharoplasty and lacrimal gland repositioning via suture suspension, two had persistent mild dry eye symptoms post-operatively that were managed with occasional usage of artificial tears. Patients were followed up for an average of 19.9 months and none had recurrence of their lacrimal gland prolapse.[27] In another study of 57 patients, seven patients required resuspension of the lacrimal gland associated with prolonged eyelid swelling, pain, or dry-eye symptoms. Patients were followed up for 12 months.[8] In a smaller study of 20 patients who had clinically significant lacrimal gland prolapse and underwent lacrimal gland repositioning, one patient complained of firmness in the site postoperatively, four complained of mild transitory pain, and one had mild unilateral recurrence of prolapse within a 3-month follow up period.[21] In none of the studies were there any cases of post-operative dacryoadenitis.

References

- ↑ Golovin, S. S. "Spontaneous Prolapse of Lacrimal Glands." Clin. Maitop. 5 (1895): 930.

- ↑ Smith JW. Spontaneous Dislocation of the Lacrimal Glands: Review of the Literature, Report of a Case, and Technic of Surgical Correction. JAMA. 1933;101(12):905-910. doi:doi:10.1001/jama.1933.02740370009003

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 Smith B, Petrelli R. Surgical Repair of Prolapsed Lacrimal Glands. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96(1):113–114. doi:10.1001/archopht.1978.03910050069017

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Alyahya GA, Bangsgaard R, Prause JU, Heegaard S. Occurrence of lacrimal gland tissue outside the lacrimal fossa: comparison of clinical and histopathological findings. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005 Feb;83(1):100-3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00365.x. PMID: 15715566.

- ↑ Georgescu D, Belsare G, McCann JD, Anderson R. Adjunctive procedures in upper eyelid blepharoplasty: internal brow fat sculpting and elevation, glabellar myectomy, and lacrimal gland repositioning. In: Massry GG, Azizzadeh B, Murphy M, eds. Master Techniques in Blepharoplasty and Periorbital Rejuvenation. New York, NY: Springer, 2011: In Press.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Smith B, Lisman RD. Dacryoadenopexy as a recognized factor in upper lid blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1983;71:629–32.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Beer GM, Kompatscher P. A new technique for the treatment of lacrimal gland prolapse in blepharoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg 1994;18:65–9.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Massry, Guy G. M.D. Prevalence of Lacrimal Gland Prolapse in the Functional Blepharoplasty Population, Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery: November 2011 - Volume 27 - Issue 6 - p 410-413 doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31821d852e

- ↑ Custer PL, Tenzel RR, Kowalczyk AP. Blepharochalasis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1985;99:424–8.

- ↑ Sen DK. Tuberculosis of the orbit and lacrimal gland: a clinical study of 14 cases. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1980;17(4):232-238. doi:10.3928/0191-3913-19800701-09

- ↑ Mojon DS, Goldblum D, Fleischhauer J, et al. Eyelid, conjunctival, and corneal findings in sleep apnea syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(6):1182-1185. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90256-7

- ↑ Goldberg R, Seiff S, McFarland J, Simons K, Shorr N. Floppy eyelid syndrome and blepharochalasis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;102(3):376-381. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(86)90014-0

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Hundal KS, Mearza AA, Joshi N. Lacrimal gland prolapse in blepharochalasis. Eye. 2004;18(4):429-430. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6700668

- ↑ Jordan DR. Blepharochalasis syndrome: a proposed pathophysiologic mechanism. Can J Ophthalmol J Can Ophtalmol. 1992;27(1):10-15.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Collin JRO. Blepharochalasis A Review of 30 Cases. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;7(3):153-157.

- ↑ Trokel SL, Jakobiec FA. Correlation of CT scanning and pathologic features of ophthalmic Graves’ disease. Ophthalmology. 1981;88(6):553-564. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(81)34993-8

- ↑ Nugent RA, Belkin RI, Neigel JM, Rootman J, Robertson WD, Spinelli J, Graeb DA. Graves orbitopathy: correlation of CT and clinical findings. Radiology. 1990 Dec;177(3):675-82. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.3.2243967. PMID: 2243967.

- ↑ Harris MA, Realini T, Hogg JP, Sivak-Callcott JA. CT dimensions of the lacrimal gland in Graves orbitopathy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(1):69-72. doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e31823c4a3a

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Friedhofer H, Orel M, Saito FL, Alves HRN, Ferreira MC. Lacrimal Gland Prolapse: Management During Aesthetic Blepharoplasty: Review of the Literature and Case Reports. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(4):647-653. doi:10.1007/s00266-008-9222-

- ↑ Nahata MC, Sethi PK. Traumatic prolapse of the lacrimal gland. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1973;21(1):43.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 21.2 Eshraghi B, Ghadimi H. Lacrimal gland prolapse in upper blepharoplasty. Orbit. 2020;39(3):165-170. doi:10.1080/01676830.2019.1649434

- ↑ Kashkouli MB, Tabrizi A, Ghazizadeh M, Khademi B, Karimi N. Supine Test: A New Test for Detecting Lacrimal Gland Prolapse Before Upper Blepharoplasty. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35(6):581-585. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001397

- ↑ Jump up to: 23.0 23.1 Tang SX, Lim RP, Al-Dahmash S, et al. Bilateral Lacrimal Gland Disease: Clinical Features of 97 Cases. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(10):2040-2046.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.018

- ↑ Eifrig CWG, Chaudhry NA, Tse DT, Scott IU, Neff AG. Lacrimal Gland Ductal Cyst Abscess. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17(2):131-133.

- ↑ Huang S, Juniat V, Satchi K, et al. Bilateral lacrimal gland disease: clinical features and outcomes. Eye. Published online November 1, 2021:1-9. doi:10.1038/s41433-021-01819-0

- ↑ Koursh DM, Modjtahedi SP, Selva D, Leibovitch I. The blepharochalasis syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54(2):235-244. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.12.005

- ↑ Guyuron B, DeLuca L. Aesthetic and Functional Outcomes of Dacryoadenopexy. Aesthet Surg J. 1996;16(2):138-141. doi:10.1016/S1090-820X(96)70037-7