Iridoschisis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

Iridoschisis is a rare condition in which the anterior and posterior stromal fibers of the iris are separated, resulting in the anterior layers disintegrating into thin fibrils with free ends floating in the anterior chamber. In 1922, Schmitt described the first case of this form of iris splitting[2] , which was later termed “iridoschisis” by Lowenstein and Foster.[3] In 1945, Lowenstein and Foster described a case of bilateral iridoschisis in a woman with end stage glaucoma, which led to enucleation. This allowed for the first histological study of the condition, which revealed deep clefts between largely atrophic anterior stromal, and posterior stromal layers.[3]

Epidemiology/Pathophysiology

There have been over 100 cases of iridoschisis reported in the literature.[4] Though a number of ideas exist, there is not yet one defining theory of the pathogenesis or etiology. Lowenstein and Foster[3] hypothesized that iridoschisis was a consequence of a glaucomatous condition or prior iris trauma. They suggested that these conditions induced an intraocular pressure (IOP) spike, forcing aqueous humor into the iris, and subsequently splitting the anterior and posterior portions of the iris stroma. Lowenstein and Foster also considered that iridoschisis may simply be the result of senile changes. This particular theory has been supported by others, who propose that, with age, there is increasing sclerosis of the irideal blood vessels, which may induce a shearing action during dilation and constriction, resulting in tearing and separation of the anterior and posterior iris stroma.[5] Ischemia in isolation is unlikely to contribute to the development of iridoschisis as evidenced by flouroiridography studies which have revealed normal perfusion of blood vessels in schitic portions of iris.[6] Some reports of iridoschisis and plateau iris configuration suggest a pathogenesis related to congenital anatomical anomaly instead of senile or traumatic changes.[7][8] Others have suggested that prolonged treatment with miotics can cause a mechanical shearing action that provokes tearing of the iris stroma.[9] However, miotics were used quite commonly in the treatment of glaucoma for many years, and there has been no associated increase in the prevalence of iridoschisis.

Histopathologic studies of eyes with iridoschisis reveal iris fibrosis and atrophy, causing clefts between the anterior and posterior stromal layers.[5] The vasculature appears largely normal in these eyes, aside from possible swelling of the endothelium. The normal vasculature on histopathalogic exam, and perfusion on fluoroiridography, differentiates iridoschisis from essential iris atrophy, further disputing the theory that the conditions are related.[10]

Clinical Characteristics

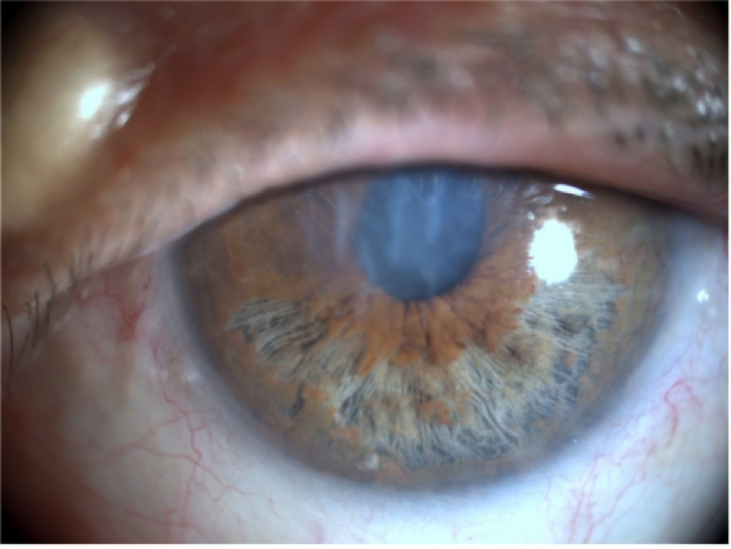

Iridoschisis is often bilateral, and presents in the fifth to seventh decade of life.[10] On slit lamp exam, the anterior iris stromal fibers can be seen floating freely in the aqueous humor. Most commonly, iridoschisis effects the inferior iris (Figure 1).[11]

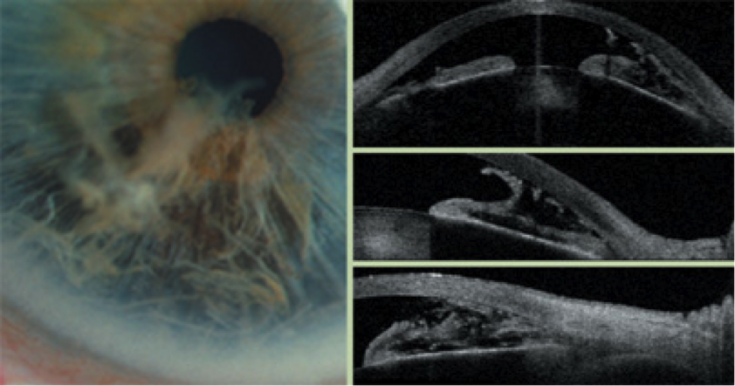

About two-thirds of reported iridoschisis cases are associated with glaucoma,[10][11] half of which are due to angle closure.[9][13] Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT) and ultrasound biometry (UBM) show cleavage of the iris stroma into two layers. These individual fibrils from the anterior stroma can cause occlusion of the angle.[14][15][16] (Figure 2).

Generally, the cornea is unaffected in cases of iridoschisis, though there are reports of bullous keratopathy secondary to endothelial damage from direct contact with floating iris strands.[5][10][17] There are also a few reports of iridoschisis in patients with keratoconus,[18] including one occurring after penetrating keratoplasty (PKP).[19] Additionally, there are a number of reports of iridoschisis associated with interstitial keratitis secondary to syphilis.[20] The patients described in these reports had systemic features of congenital syphilis, with interstitial keratitis in addition to iridoschisis and occasionally open angle glaucoma.

Cases of iridoschisis associated with presenile cataracts, and with capsular delamination have been described.[13][21][22] Iridoschisis has also been associated with both anterior and posterior lens subluxation.[20][23] Cases with anterior lens subluxation may be an association with iridoschisis, or precipitation of it from a narrowed anterior chamber and subsequent mechanical trauma between the lens and iris.

Inheritance

There is one case report describing a family with iridoschisis, accompanied by narrow anterior chambers and presenile cataracts.[21] This case report proposed an autosomal dominant inheritance of the condition, suggesting that family members of patients with this condition should be screened.

In another case report, a 50-year-old patient with iridoschisis and her asymptomatic daughter underwent high-frequency ultrasound imaging.[24] As expected, the patient exhibited diffuse iris stromal changes with an intact posterior iris pigmented layer, while imaging of her daughter showed discrete but less severe iris stromal changes, suggesting a hereditary component, and spectrum of severity, to the condition.

Differential Diagnosis

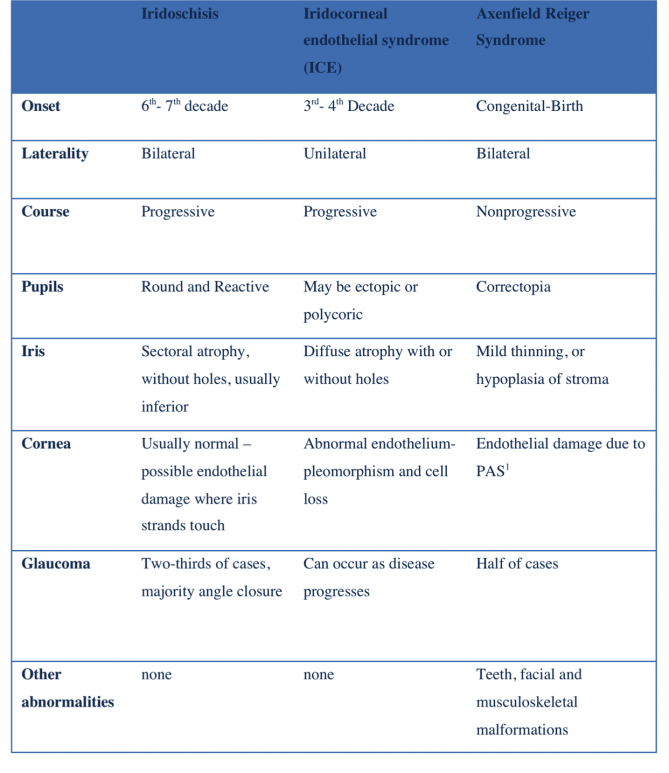

The differential diagnosis of iridoschisis includes two other conditions affecting the iris stroma - Iridocorneal Endothelial Syndrome (ICE) and Axenfeld-Reiger syndrome. ICE most often presents as a unilateral, progressive finding in the third to fourth decade of life, in contrast to iridoschisis which is often bilateral and presents in the fifth to seventh decade of life.[25][26] While iridoschisis is characterized by stromal splitting in a single, usually inferior, iris sector, ICE syndrome can present with stromal atrophy and iris holes, as well as peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) that extend to Schwalbe’s line. As a result of the pulling of the iris by PAS, ICE syndrome patients can have corectopia and polycoria. Corneal endothelial pleomorphism and endothelial cell loss can also be seen in ICE syndrome, whereas the cornea is often unaffected in iridoschisis, unless iridocorneal touch is present.

Axenfeld-Reiger syndrome, in contrast to both iridoschisis and ICE, is present at birth, bilateral, and is nonprogressive.[25][26] Patients with Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome characteristically have iris atrophy that can lead to holes, as well as PAS, and posterior embryotoxin. Key differences between these three conditions are highlighted in the table below.

Glaucoma

About two-thirds of all reported cases of iridoschisis have been associated with some form of glaucoma. Partial or complete angle closure accounts for about half of iridoschisis-associated glaucoma, however, whether iridoschisis is the cause or result of angle-closure is still not certain.[27][28][29] Romano et al examined six cases of patients with iridoschisis and angle closure glaucoma in which iridoschisis was documented prior to any angle closure attack, concluding that in these cases, iridoschisis may have precipitated the angle closure.[27] Salmon et al examined 12 patients with iridoschisis, and found that all patients had partial or complete angle closure on gonioscopy, particularly in the superior angle.[29] In these patients, IOP ranged from 12 to 65 mmHg, and the majority had a history intermittent headaches and eye pain. These authors hypothesized that the presence of intermittent headaches and eye pain suggested subacute angle closure where intermittent elevations in IOP were provoking iris stromal atrophy.[29]

The mechanism by which iridoschisis may cause angle closure is still under speculation. Some have theorized that the free floating anterior stromal fibers bow forward, coming into contact with the trabecular meshwork resulting in IOP elevation and angle closure.[24] Danias et al used high frequency ultrasound to show that the intact posterior pigment epithelium may drape over the anterior capsule of the lens and cause a form of pupillary block, while the anterior stromal fibers bow forward to obstruct the angle. Others have proposed that the pigment released from the stromal atrophy may clog the trabecular meshwork;[17] however, Salmon and associates questioned this idea given that the majority of iridoschisis patients respond to medical management.[29]

Shima et al reported a case of iridoschisis and plateau iris configuration. UBM revealed an anteriorly displaced ciliary body, narrowing of the iridocorneal angle, and a plateau iris configuration in all four quadrants.[7] The authors suggested that UBM be performed in cases of angle-closure glaucoma associated with iridoschisis to differentiate between the presence of pupillary block and a plateau iris configuration.

Management

As two-thirds of cases of iridoschisis are associated with glaucoma, all patients should have baseline glaucoma testing, including visual field, optical coherence tomography, gonioscopy, tonometry, pachymetry, and optic nerve head exam. Even in the setting of normal baseline testing, patients should still be closely monitored for glaucoma development. Most cases of iridoschisis with elevated IOP have been reported to respond to medical management alone.[29] Laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) is often performed in patients with angle closure in the setting of iridoschisis, not undergoing cataract surgery. However, some have suggested that phacoemulsification combined with goniosynechiolysis offers superior treatment to LPI alone in these patients.[30] Trabeculectomy can be performed in cases in which the IOP is not adequately lowered with medical management.[7][23][29]

Phacoemulsification can be more difficult in patients with iridoschisis due to poor pupillary dilation, and is associated with greater risk and complication due to the potential for iris stromal and sphincter muscle damage.[4] The frayed, free-floating anterior stromal fibers can present a particular challenge during cataract surgery. Several methods of management have been described, including the use of cohesive ophthalmic viscosurgical devices (OVD) to create a barrier atop the stromal fibers,[31] as well as the use of the vitreous cutter and Vannas scissors to amputate the fibers.[32] More recently, the use of microcautery applied to the iris cords in patients with iridoschisis has been described.[33] The authors note that the particularly appealing aspects of this approach are the low cost, ease of use, preservation of tissue, and maintenance of the structural collagen.

In cases of iridoschisis complicated by bullous keratopathy and corneal decompensation, non-Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty (nDSAEK) and Descemet’s Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK) have been successfully employed.[34][35]

Additional Resources

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Iridoschisis. https://www.aao.org/image/iridoschisis-2 Accessed 18 October, 2017.

References

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Iridoschisis. https://www.aao.org/image/iridoschisis-2 Accessed October 18, 2017.

- ↑ Schmitt A. Ablosung des vorderen irisblattes. Augenh Klin Mbl. 1922;68:214–215. Loewenstein A, Foster J. Iridoschisis with multiple rupture of stromal threads. Br J Ophthalmol. 1945; 29:277–282

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 Loewenstein A, Foster J. Iridoschisis with multiple rupture of stromal threads. Br J Ophthalmol 1945; 29: 277-282

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Pieklarz, B., Grochowski, E. T., Saeed, E., Sidorczuk, P., Mariak, Z., & Dmuchowska, D. A. (2020). Iridoschisis-A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(10), 3324.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Albers EC, Klien BA. Iridoschisis: A clinical and histopathologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1958;46:794–802

- ↑ Carnevalini A, Menchini U, Bandello F et al. Aspects fluoroiridographiques de L ‘Iridoschisis. J Fr Ophthalmol 1988; 11:329-32

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 Shima C, Otori Y, Miki A, et al. A case of iridoschisis associated with plateau iris configuration. Jpn J Ophthalmology. 2007;51:390–391.

- ↑ Chapman KO, Demetriades AM. Juvenile iridoschisis and incomplete plateau iris configuration. J Glaucoma 2011; 24(5):142-4

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Payne TD, Thomas RP. Iridoschisis: A case report. Am J Ophthalmol 1966; 62: 966-967

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Gogaki E, Tsolaki F, Tigania S, Skatharoudi, C, and Balatsoukas, D. Iridoschisis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011; 5: 381–384.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Schoneveld PG, Pesudovs K. Iridoschisis. Clin Exp Optom. 1999; 82:29–33

- ↑ Gogaki E, Tsolaki F, Tigania S, Skatharoudi, C, and Balatsoukas, D. Iridoschisis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011; 5: 381–384.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Porteous A, Low S, Younis S, Bloom P. Lens extraction and intraocular lens implant to manage iridoschisis. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 201;43(1):82-3

- ↑ Steinert RF. Bringing a Versatile Tool to the Anterior Segment Surgeon.Ophthalmology Management Issue: June 2007

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Steinert RF, Huang D. Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography. 2008 p134

- ↑ Agard E, Malcles A, El Chehab H, Ract-Madoux G, Swalduz B, Aptel F, Denis P, Dot C. [Iridoschisis, a special form of iris atrophy.] J.Fr Ophthalmol 2013 Apr;36(4):368-71

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Rodrigues MC, Spaeth GL, Krachmer JH, Laibson PR: Iridoschisis associated with glaucoma and bullous keratopathy. Am J Ophthalmol1983, 95; 73-81

- ↑ Eiferman RA, Law M, Lane L. Iridoschisis and keratoconus. Cornea 1994; 13:78-79

- ↑ Petrovic A, Kymionis G. Massive iridoschisis after penetrating keratoplasty successfully managed with nd:Yag punctures: A case report. Eur J Ophthalmol 2019 May 31.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 Foss AJ, Hykin PG, Benjamin L. Interstitial keratitis and iridoschisis in congenital syphilis. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1992;12:167–170

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 Mansour AM. A family with iridoschisis, narrow anterior chamber angle, and presenile cataract. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet. 1986;7:145–149

- ↑ Chen, H. S.-L., Kang, E. Y.-C., & Wu, W.-C. (2020). Capsular delamination of the crystalline lens and iridoschisis. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. Journal Canadien d’ophtalmologie, 55(4), 343–344.

- ↑ Jump up to: 23.0 23.1 Agrawal S, Agrawal J, Agrawal TP. Iridoschisis associated with lens subluxation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:2044–2046.

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 Danias J, Aslanides IM, Eichenbaum JW, Silverman RH, Reinstein DZ and Coleman DJ. Iridoschisis: high frequency ultrasound imaging. Evidence for a genetic defect? Br J Ophthalmol. 1996 Dec; 80(12): 1063–1067

- ↑ Jump up to: 25.0 25.1 Kanski JJ. Clinical Ophthalmology, 3rd ed.Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann 1998: 267

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 Shields MB, Buckley E, Klintworth GK, et al. Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome. A spectrum of developmental disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 1985;29:387–409

- ↑ Jump up to: 27.0 27.1 Romano A, Treister G, Barishak R, Stein R. Iridoschisis and angle-closure glaucoma. Ophthalmologica 1972; 164: 199-207

- ↑ Posner A and Gorin G: Iridoschisis and glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmoll 958, 45: 451-2

- ↑ Jump up to: 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 Salmon JF and Murray DN. The association of iridoschisis and primary angle-closure glaucoma. Eye (Lond) 1992;6:267–272

- ↑ You, Z., Qin, Y., Li, G., & Shi, K. (2017). Goniosynechialysis combined with cataract extraction for iridoschisis. Medicine, 96(42), e8295.

- ↑ Lee, E. J., Lee, J. H., Hyon, J. Y., Kim, M. K., & Wee, W. R. (2008). A case of cataract surgery without pupillary device in the eye with iridoschisis. Korean Journal of Ophthalmology: KJO, 22(1), 58–62.

- ↑ Ghanem VC, Ghanem EA, Ghanem RC. Iridectomy of the anterior iris stroma using the vitreocutter during phacoemulsification in patients with iridoschisis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29(11):2057-9

- ↑ Snyder ME, Malyugin B, Marek SL. Novel approaches to phacoemulsification in iridoschisis. Canadian J Ophthalmol 2019;54: e221-225.

- ↑ Minezaki T, Hattori T, Nakagawa H, Kumakura S, Goto H. Descemet's stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty for bullous keratopathy secondary to iridoschisis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1353-5.

- ↑ Greenwald MF, Niles PI, Johnson AT, Vislisel JM, Greiner MA. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty for corneal decompensation due to iridoschisis. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2018 Jan 5;9:34-37.