History of American Civil War Ophthalmology

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

American Civil War ophthalmologists accounted for a small portion of military physicians and were often limited by 19th-century medical knowledge. Nonetheless, they attempted to provide the highest quality of care and significantly contributed to Civil War medicine.

Introduction

Physicians during the American Civil War faced many challenges due to the era’s pre-modern medical practices and wartime conditions. Providers lacked the current understanding of the causes of disease and underwent comparatively less robust medical training. They were also preoccupied with the conflict which hampered the application of overseas advances. However, many military ophthalmologists received above average training and were arguably some of the most qualified physicians in the conflict. Practitioners conducting ophthalmological procedures in the Union and Confederate militaries attempted to provide the best medical care available in their 19th-century context.

Medical Context

Extent of Conflict

The Civil War left over one million dead or wounded, with 359,528 Union deaths and about 200,000 Confederate deaths.[1][2] This carnage has led some to call it one of the greatest wars of the 19th-century.[3] These devastating numbers partially resulted from the utilization of European advances in modern warfare, such as the deadly Minié ball (fig. 1).[4] The conflict lasted four years, beginning in South Carolina on April 12, 1861, with the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter and ending after Lee’s surrender to Grant on April 9, 1865, in the Virginian town of Appomattox Courthouse. The effect of disease was immense, with more soldiers dying to medical illness than combat, demonstrated by only 110,070 battle related Union deaths out of 359,528 total Union deaths.[2][5]

State of Military Medicine

The respective Union and Confederate Army Medical Departments, where military ophthalmologists served, were unprepared for the number of casualties the war inflicted.[1][6][3] At the beginning of 1861, the Union Medical Department was responsible for the treatment of 16,000 soldiers, and was staffed by only 112 providers. In addition, the Army’s medical system was disorganized and often ineffective early in the war. Eventually, the Union’s Medical Department, often edged on by the civilian Sanitary Commission, began adapting to meet the mounting medical needs. The number of doctors eventually rose to over 12,000 in 1865, and three new medical officer groups were established.[3]

The Confederates suffered a similar situation, with the new Confederacy having little to no previous combat medical experience. Their military hospitals were “confused and depressing” at the war’s opening, and only $50,000 was initially appropriated for their establishment and maintenance. However, the work of the Confederate Medical Department improved over the war, which was reflected by the dozens of new hospitals they established. Eventually, the Confederacy employed over 3,000 surgeons.[7]

Pharmaceuticals

Essential pharmaceuticals used in current practice were not available to Civil War physicians. Antibiotics did not come into wide use until World War II, there were no steroids for the treatment of inflammation, and available medications had limitations.[8][9][5] The revolutions in medicine that occurred due to the work of Pasteur, Lister, and the like impacted American medicine too late to affect Civil War practice.[5]

Despite limitations, there were useful techniques and pharmaceuticals available. Surgeons induced surgical anesthesia with chloroform and ether (fig. 2), antiseptics were utilized, carbolic acid was employed as a disinfectant, sulfuric and several other acids were used to treat gangrene, hospital air was purified with iodine, ophthalmia was treated with potassium iodide, and erysipelas and pyemia were treated with tincture of iodine.[3][8][5][9] Additionally, the Confederacy employed natural remedies based on native flora due to the Union blockade, though their effectiveness is difficult to chart.[10] Nonetheless, since surgeons were not yet aware of the underlying causes of infection or the reasons for antiseptics’ effectiveness, less effective treatment and timing was common.[3][7]

Military Physicians

Lastly, a brief examination of military physicians (fig. 3) as a whole is insightful in order to draw comparisons between the average physician and the average ophthalmologist of the time. One seminal work wrote that the “best” Union military physicians, “by modern standards, … were deplorably ignorant and badly trained” and Southern medical graduates were “ill-prepared by present standards” to go into practice.[3][5] Nonetheless, Civil War military physicians were better prepared than the generation before. Almost all Civil War doctors held medical diplomas, though American medical schools were “never worse” than in the mid-nineteenth century.[3] Although this description might characterize most surgeons, there were remarkable exceptions to this generalization, including in the field of ophthalmology. Civil War physicians’ methods were “as modern to them as anything doctors do today,” but were limited by their era.[11]

Military Ophthalmologists

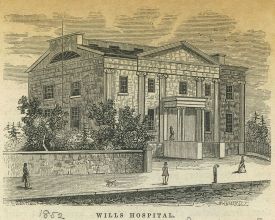

As explained above, Civil War physicians faced many challenges, including those providing ophthalmological care. There was not an adequate number of “well trained” ophthalmologists serving in the Northern and Southern militaries relative to eye care needs.[5] This situation was mainly due to the specialty’s infancy prohibiting it from supplying the necessary number of practitioners to the war. Many of the best trained physicians practiced in the major cities, far from the field hospitals (fig. 4).[5]

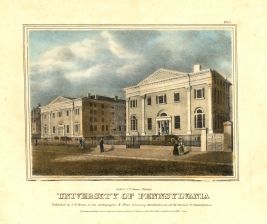

Though limited in magnitude, many ophthalmologists served the Union and Confederacy relative to the specialty’s small size. For example, the University of Pennsylvania, Jefferson Hospital, and Wills Hospital staffed the Union’s military with several then well-known ophthalmologists.[6] Additionally, ophthalmologists in the Confederacy included the European trained Julian John Chisolm who greatly contributed to the development of the Confederate Medical Department as a whole.[6][12]

Casualty Statistics

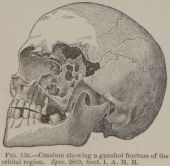

Ophthalmic injuries accounted for 0.09% of all hand-to-hand combat wounds and direct strikes from projectiles, totaling 1,190 recorded cases, not factoring ocular burns, tattooing, percussion caps injuries, and adnexal wounds.[6] 64 soldiers, or about 5%, died as a result of their injuries. Some diseases (table 2) included ophthalmia (caused by conjunctivitis, keratitis, and uveitis), staphyloma (fig. 5), and pterygium.[5]

| EXTENT OF INJURY | Cases. | Died. | Duty. | Discharged. | Unknown. |

| Destroying sight of both eyes | 63 | 17 | …… | 44 | 2 |

| Destroying sight of right eye | 393 | 12 | 87 | 286 | 8 |

| Destroying sight of left eye | 387 | 24 | 95 | 258 | 10 |

| Destroying sight; side not given | 45 | 11 | 9 | 17 | 8 |

| Totals for destroying of sight | 888 | 64 | 191 | 605 | 28 |

| Injuring sight of right eye | 25 | …… | 9 | 13 | 3 |

| Injuring sight of left eye | 20 | …… | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| Injuring sight; side not stated | 6 | …… | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Totals for injuring of sight | 51 | …… | 18 | 23 | 10 |

| Undetermined cases; right eye | 106 | …… | 71 | 24 | 11 |

| Undetermined cases; left eye | 116 | …… | 83 | 20 | 13 |

| Undetermined cases; side not stated | 29 | …… | 16 | 7 | 6 |

| Totals for undetermined cases | 251 | …… | 170 | 51 | 30 |

| Aggregate | 1190 | 64 | 379 | 679 | 68 |

The most common result of injuries and complications from treatment was loss of sight (“destroying sight”) of one or both eyes and exhibited a 7% death rate, higher than the average eye-related death rate of 5%. It was more common to harm only one eye than both, with almost nine-tenths of cases specifying one eye and only about one-twentieth of cases specifying both eyes. When only one eye was affected, the distribution of injuries was about even between the left and right eye.[13]

| Area Affected | Disease |

| Conjunctiva | Pterygium

Symblepharon Anchyloblepharon Gonorrhoeal [sic] ophthalmia |

| Cornea | Staphyloma

Leucoma |

| Eyelids | Blepharitis

Entropion Ectropion |

Military Practice

The conflict did not significantly employ recent European advances in medicine nor contribute to the development of medical science during the period, despite utilizing modern European advances in warfare.[1] As such, the conflict generally employed standard 19th century American medical means. Nonetheless, the conflict did greatly precipitate more professional communication among physicians. The field of ophthalmology mirrors many aspects of these situations, though with some differences.

Ophthalmological Treatment

The conflict itself brought little ophthalmological advancement in techniques or anatomic knowledge, and it did not employ the remarkable innovations of the “Golden Age of Ophthalmology.”[14][5] Reasons for this included the slowness of knowledge dissemination, poor equipment, less than optimal 19th-century transportation, American physicians being preoccupied with the conflict, and most advances existing in isolation from the battlefield since they were the result of academic prowess, not wartime necessity.[5][6] Also, general hostility towards medical specialization restricted progression, manifesting itself in ophthalmology due in part to “quacks” and “charlatan[s]” (fig. 6) overrunning ophthalmic care earlier in the 19th-century.[15]

Standard 19th-century care consisted of many treatments dating back to the Napoleonic Wars four decades earlier.[5] Treatments included administering leeches for cathartics, venesection, and blistering agents, and applying pastes of lead acetate or plombage (since it was believed to reduce granulation size) and administering atropine, colchicine, potassium iodide, and iron for treating ophthalmia.[5][16][17] Topical anesthesia was not yet adopted in ophthalmology, though chloroform and ether were used for general anesthesia.[18]

Many ophthalmologists were also inexperienced with advances in 19th-century medical instruments, reflected by the very few military surgeons who could use the ophthalmoscope, despite it being invented about a decade earlier.[3] However, the actual impact of the ophthalmoscope presumably would have been minimal since the light source was an oil lamp or sunlight (fig. 7), and it was not until 1885 that an electric light was added, making it far more practical.[2]

Another aspect of military eye care was examinations. In the North, physical examinations of incoming troops were often lenient and caused many under robust persons to enter the army.[2] In 1865 nearsightedness was considered acceptable, complete loss of sight in the right eye was unacceptable, and partial loss of sight in both eyes was also unacceptable.[3] In the South, an 1863 order explained individuals with “opacity of one cornea, or the loss of one eye” were able to serve.[7]

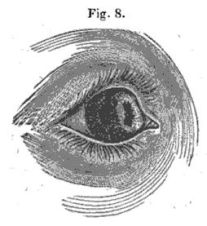

Despite traditional methods being the mainstay of practice, there are many relatable aspects of 19th-century practice to the present. Some examples are in the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, published from 1870-1888 and written by Civil War physicians, which chronicles the conflict’s documented injuries. Dr. Mark Breazzano, Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology at Johns Hopkins University, in commenting on parts of the ophthalmological section of the volumes, explained that the military surgeons provided good documentation and possessed a fine understanding of anatomy in several cases, but they faced limitations in pathophysiology (fig. 8).[19] Additionally, Dr. Breazzano commented on the following passage, where the editors reflected on lessons learned from the conflict,

"When general opthalmitis [sic] has followed a gunshot injury, a free horizontal incision, evacuating the contents of the eyeball, should not be long delayed. Absolute rest, and strict diet, and every precaution that may conduce to the preservation of the remaining eye, should, with sedulous solicitude, be enjoined by the surgeon."[13]

Dr. Breazzano notes that despite a large insertion on the eye sounding “barbaric,” even today large insertions are sometimes necessary to remove foreign bodies. He also notes that modern techniques such as vitrectomy using microscopic forceps or a kidney stone basket simply did not exist, and that this historical setting left surgeons with limited options. [19]

Other examples include the establishment of hospitals and wards dedicated to treating the eye. In the North, one of the Union’s “eye and ear infirmaries” operated in St. Louis, and in 1863 Desmarres Hospital was established to treat eye injuries in Washington, DC.[3][2] In the South, the military established a ward for eye diseases in 1864 at Forsyth, Georgia, and shortly afterward formed an ophthalmic hospital in Athens, Georgia.[7]

There were a limited number of advancements in eye-related medicine as a direct consequence of the conflict. The first “truly integrated ocular implants” may have been provided to Civil War veterans,[4] and Confederate physicians discovered that the prolonged blurred vision that resulted from the use of atropine to dilate pupils could be shortened by an extract of Calabar bean. It was discovered far later that the active ingredient was physostigmine (fig. 9), which is still used for this purpose.[2]

Ophthalmological Communication

The field of eye surgery saw notable communication of ophthalmological knowledge during the conflict. Julian John Chisolm’s work, A Manual of Military Surgery for the Use of Surgeons in the Confederate Army, is a notable example. Chisolm (fig. 10) himself was an accomplished physician who studied under French ophthalmologist Louis-Auguste Desmarres and observed wartime medicine in the Austro-Italian War. He also became the youngest Professor of Surgery in America and returned to Europe to further study the eye after the war.[12][2]

Published in three editions from 1861 to 1864, Chisolm’s work is considered the “most valuable and the most inclusive” medical treatise used by the Confederacy.[12] However, it demonstrates the period’s limited extent of ophthalmologic knowledge. The Manual mentions eye ailments only in a handful of instances, and the most exhaustive section on the eye, only about a paragraph, explained that the “most distressing injuries of the face are those involving vision.” Chisolm provides little advice for treating eye ailments, stating that when both eyes are destroyed, the optic nerve is damaged, or the ganglion is wounded by gunshot, there is “no remedy,” and concluded that this untreatable state was due to the development of “general opthalmia [sic].”[20]

Nonetheless, the Manual did encourage trends towards current practices. Chisolm praised the use of opium and especially morphine, imploring physicians that opium “should never be absent from reach” and implies it should be used in conjunction with ophthalmic surgery. One case study provided to physicians in the Manual involved a civilian operation where Chisolm administered morphine to treat a patient’s pain due to a failed attempt of “cataract by division of the lens.”[20]

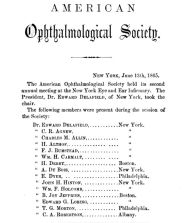

The Confederate States Medical and Surgical Journal in the South and Jones on Diseases of the Eye in the North also kept physicians informed.[5] Jones on Diseases was listed on the Union’s Standard Table for orderable medical and hospital supplies, and the Union purchased 576 copies throughout the war.[21][22] The first eye journal in America, the American Journal of Ophthalmology, as well as the American Ophthalmological Society (fig. 11), were also established during this period.[5][2]

Case Study

The abilities of Civil War physicians become more apparent with an examination of one of the cases recorded in The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (MSHWR). Patient Pt. J.M. Elliott, a 29-year-old who served in the 30th Kentucky, was treated multiple times for “pannus covering cornea of right eye” in 1865, a few months after the war ended. His physician was Dr. Joseph Sullivan Hildreth, though it is unclear if he performed only the last procedure, called “Hancock’s operation,” or each surgery. After the procedures, the patient became totally blind and developed staphyloma in both corneas.[23]

| NO. | NAME, MILITARY DESCRIPTION, AND AGE. | INJURY OR DISEASE. | OPERATION AND OPERATOR. | RESULT AND REMARKS. |

| … | ||||

| 19 | Elliott, J.M., Pt., H, 30th Kentucky, age 29. | Pannus covering cornea of right eye; total obseurity [sic] of vision. | Aug. 25, syndectomy. Pannus connecting necessitated re-operation. Sept. 9, disease reproducing itself. Hancock’s operation performed Oct. 7. Surg. J.S. Hildreth, U.S.V. | Left hospital Oct. 16, 1865; pens’d. Totally blind; complete opacity and staphyloma of both cornea [sic]. |

Although this case provides limited information, comparing the patient’s case to similar contemporary accounts shines a light on what might be the details of his operation. One such civilian case describes the treatment of corneal pannus by syndectomy as consisting of removing “one-eight of an inch of conjunctiva and subconjunctival tissue … from around the cornea.” This civilian case study stated that the procedure often yielded successful outcomes.[24]

In another similar civilian case, although treating glaucoma rather than pannus, describes Hancock’s operation as consisting of the following,

"[cutting] a section of conjunctiva and sclerotica [sic] radiating from the corneo-sclerotic juncture, midway between the inferior and external rectus, obliquely downwards and backwards to the extent of about the eighth of an inch."[25]

What is significant about Hancock’s operation is that it may have been first performed in America in 1861, demonstrating that the patient’s physician was apprised of and able to apply recent medical knowledge.[25]

Also worthy of note is the patient’s surgeon himself. Dr. Hildreth was an accomplished ophthalmologist, who graduated from the University of Pennsylvania’s Medical Department in 1856 (fig. 12). He had studied under Desmarres, a leading European ophthalmologist whose work is still impactful today, and Virchow, who pioneered microscopy, cell theory, and modern pathology.[9] Hildreth also was one of the earliest members of the American Ophthalmological Society and was considered by one author as among the “greatly skilled” ophthalmologists who helped bring American ophthalmology into its own specialty.[26][27] As such, the patient seemed to have received care from among the most qualified surgeons in the military.

The patient survived the initial disease, multiple operations, received standard or arguably advanced treatments for his time, and received care from a well-qualified specialist. In many respects, this case demonstrates the success of Civil War medicine. Nonetheless, the patient faced a negative outcome, becoming totally blind and developing opacity and staphyloma in both corneas.

It is difficult to conclude if the patient’s negative outcome resulted from the boundaries in 19th-century medical knowledge, the ability of other practitioners if involved, limits in his physician’s skill, or other factors.[9] The period’s unawareness of the bacterial cause of inflammation may have led to staphyloma, if less qualified physicians preformed before Dr. Hildreth, they may have unintentionally scared the cornea contributing to opacity, and many of Dr. Hildreth’s operations resulted in negative outcomes, possibly insinuating he faced challenges during the procedure.[9] These causes are wholly speculative due to the lack of additional detail, but their viability reflects ophthalmology’s state during the period and the challenges of Civil War ophthalmologists.

Conclusion

The American Civil War caused many medical challenges, ranging from gunshot wounds to stifling American medical advancements. Although well-intended, many military physicians were significantly less trained compared to current standards and employed traditional practices. Although these generalizations can be applied to ophthalmology, the specialty also exemplifies some of the most qualified and well-versed physicians in the conflict. Regardless of the ocular care provider’s training and knowledge, military ophthalmologists provided the best care that they were capable of in a 19th-centruy wartime context.

Additional Resources

Source: YouTube. National Museum of Civil War Medicine, Mark Breazzano, MD and John Lustrea. https://youtu.be/rEfl-hF_SMk Accessed January 13, 2023.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 Humphreys M. Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1353/book.23993. Accessed January 15, 2023.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Bollet AJ. Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs. Tucson, AZ: Galen Press; 2002.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Adams GW. Doctors in Blue: The Medical History of the Union Army in the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press; 1996.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 Hughes MO. Eye Injuries and Prosthetic Restoration in the American Civil War Years. Journal of Ophthalmic Prosthetics. 2008;13:7-28. https://wordpress.artificialeyeclinic.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/civilwar.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2023.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 Hertle RW. Ophthalmic Injuries and Civil War Medicine. Documenta Ophthalmologica. 1997;94(1–2)123-137. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02629686. Accessed January 15, 2023.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Thach AB ed. Ophthalmic Care of The Combat Casualty. Falls Church, VA: U.S. Army Office of The Surgeon General; 2003.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Cunningham HH. Doctors in Gray: The Confederate Medical Service. 2nd ed. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press; 1993.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Flannery MA, Humphreys M. Civil War Pharmacy: A History. Tuscaloosa: Southern Illinois University Press; 2017.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Lowry TP. Civil War Eye Surgeon. National Museum of Civil War Medicine. https://www.civilwarmed.org/surgeons-call/eye-surgeon/. Accessed January 15, 2023. Originally published in Surgeon’s Call, May 2011.

- ↑ Hasegawa GR. Southern Resources, Southern Medicines. In Schmidt JM, Hasegawa GR, eds. Years of Change and Suffering: Modern Perspectives on Civil War Medicine. Roseville: Edinborough Press; 2009:107-126.

- ↑ Rutkow IM. Bleeding Bule and Gray: Civil War Surgery and the Evolution of American Medicine. New York: Random House; 2005.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 Welch RB. Julian John Chisholm M.D.: Confederate Surgeon, Ophthalmologist and Hospital Founder. Documenta Ophthalmologica. 1999;99(3):273-284.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Otis GA, Barnes JK. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Part I:(Vol. II). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1870.

- ↑ Albert DM. The Ophthalmoscope and Retinovitreous Surgery. In The History of Ophthalmology. Albert DM, Edwards DD, eds. Boston: John Wiley and Sons; 1996.

- ↑ Rosen G. The Specialization of Medicine: With Particular Reference to Ophthalmology. Medicine & Society in America. Arno Press and The New York Times; 1972.

- ↑ Edwards DD. Microbiology of the Eye and Ophthalmia. In The History of Ophthalmology. Albert DM, Edwards DD, eds. Boston: John Wiley and Sons; 1996:147-163.

- ↑ Albert DM, Scheie HG. A History of Ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C Thomas Publisher; 1965.

- ↑ Calvano CJ, Enzenauer RW, Johnson AJ. Ophthalmology in Military and Civilian Casualty Care. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14437-1. Accessed January 15, 2023.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 Breazzano M, Lustrea J. Eye Injuries in the Civil War with Mark Breazzano, MD. National Museum of Civil War Medicine; September 10, 2021 [video]. https://www.civilwarmed.org/event/eye/. Accessed January 15, 2023.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 Chisolm JJ. A Manual of Military Surgery, for the Use of Surgeons in the Confederate States Army; with Explanatory Plates of All Useful Operations. Columbia: Evans and Cogswell; 1864.

- ↑ Barnes JK. Abstract ‘A.’ In Stanton EM. Annual Report of the Secretary of War. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1866.

- ↑ Grace W. The Army Surgeon’s Manual, for the Use of Medical Officers, Cadets, Chaplains, and Hospital Stewards. New York: Bailliere Brothers; 1864.

- ↑ Otis GA, Huntington DL, Barnes JK. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Part III:(Vol II). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1883.

- ↑ Lawson G. Inoculation and Syndectomy. Laurence JZ, Windsor T, eds. The Ophthalmic Review: A Quarterly Journal of Ophthalmic Surgery & Science. 1865;1:285.

- ↑ Jump up to: 25.0 25.1 Bumstead FJ. Glaucoma - Hancock’s Operation for the Division of the Ciliary Muscle - Result Successful. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal; 1861:64:247-249

- ↑ Hubbell AA. The Development of Ophthalmology in America, 1800 to 1870: A Contribution to Ophthalmologic History and Biography. Chicago: W. T. Keener; 1908.

- ↑ American Ophthalmological Society. Historical Member List. Updated August 18, 2022. http://www.aosonline.org/about/history/historical-member-list/. Accessed January 15, 2023.