Hereditary Benign Intraepithelial Dyskeratosis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Hereditary Benign Intraepithelial Dyskeratosis (HBID) is a benign disease of the conjunctiva, cornea, and oral mucosa[1][2]. HBID follows a Mendelian autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with high penetrance. Due to the classic sign of marked, bilateral conjunctival hyperemia, this disease is sometimes referred to as the "red eye" disease[1].

Disease Entity

History

Hereditary Benign Intraepithelial Dyskeratosis (HBID) was first characterized in 1959 by Ludwig Von Sallman M.D., David Paton M.D., and Carl Witkop D.D.S. while studying the Haliwa-Saponi Indian tribe of Eastern North Carolina. Together, they examined over 300 patients in the Haliwa geneology, 74 of which had clinical signs and symptoms of the ocular surface or oral mucosa[1][2]. The nutritional status of this patient population was closely analyzed in order to rule out vitamin A deficiency as a cause for mucus membrane lesions. In 1981, Mclean et al diagnosed the first two cases of HBID without any known Haliwa-saponi ancestry in Waco, Texas[4]. Since 1959, several other cases have been discovered across North America, South America, Europe, and Asia. Some of these patients have ancestory tracing to the Haliwa-Saponi tribe, while others do not[5][6][7].

Risk Factors

- Chromosome 4q35 duplication[8]

- Missense mutation M77T on NLRP1 gene, chromosome 17p13.2[9]

- Haliwa-Saponi ancestry[1][2]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of HBID is unknown. The disease process involves acanthosis, dyskeratosis, and parakeratosis of the stratified squamous epithelium of the cornea and oral mucosa[3]. However, the etiology of these cellular changes has not been elucidated.

Diagnosis

Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis is a clinical or histopathologic diagnosis.

Physical examination

Routine slit lamp biomicroscopy with slit lamp photography is warranted to monitor patients with HBID and assess for progression of plaque size or corneal neovascularization.

Signs

Affected patients may have ocular involvement, oral involvement, or both.

Oral manifestations[2][10][11]:

- White, spongy plaques of the buccal mucosa, tongue, or lips

Ocular manifestations[1]:

- Bilateral, conjunctival injection

- Bilateral or unilateral whitish-gray, elevated, gelatinous corneal plaques located in the perilimbal area, most often nasally or temporally

- Superficial or deep corneal neovascularization

- Presentation in early childhood

- Waxing and waning pattern

- Excerbation during warm weather

- Excerbation and recurrence after plaque excision

Symptoms

Bilateral, marked, red eyes is the most common symptom due to bulbar conjunctival hyperemia. For this reason, the Haliwa-Saponi tribe members call this disease the “red eye disease”. Patients with HBID have reported a stigma of eye redness which is commonly confused for drug or alcohol abuse[3]. Patients also may experience discomfort, tearing, photophobia, burning, foreign-body sensation, or decreased visual acuity. Patients tend to have exacerbations of symptoms in the spring and summer months but alleviation in cooler weather[1][12].

Clinical diagnosis

Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis has a distinct clinical picture. Diagnosis can be made by slit lamp biomicroscopy alone. Affected patients may have ocular involvement, oral involvement, or both. Oral manifestations of the disease include white, spongy plaques of the buccal mucosa, tongue, or lips[13]. Ocular manifestation of the disease is characterized by bilateral, conjunctival injection with whitish-gray, elevated, gelatinous corneal plaques located in the perilimbal area, most often nasally or temporally[1][2][14]. The corneal plaques may become visually significant with extension into the central visual axis, disruption the normal ocular surface, or induction of astigmatism. Corneal neovascularization can occur around areas of plaque formation. Most commonly, neovascularization develops superficially, but involvement of the mid to deep stroma has been reported[15].

Although originally thought to be congenital, HBID is not present at birth. Symptoms begin in early childhood and follow a waxing and waning pattern throughout life. Few reports have suggested that plaques spontaneously shed, however there has never been photographic documentation of this phenomenon. Excision of plaques leads to recurrence and further exacerbation in most cases[3].

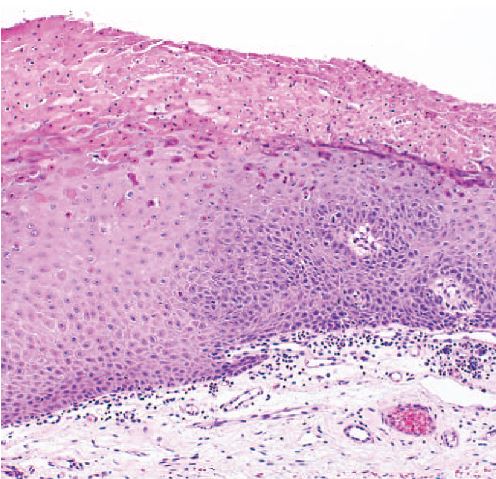

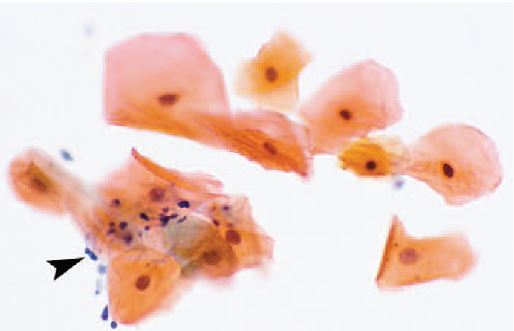

Histopathologic diagnosis

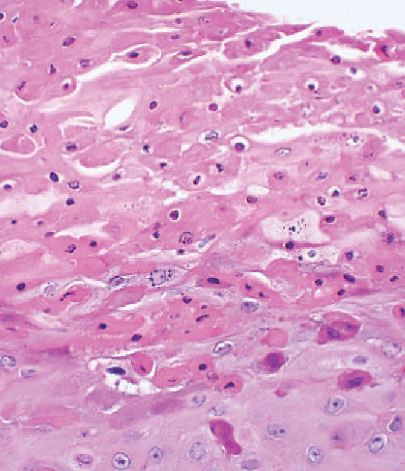

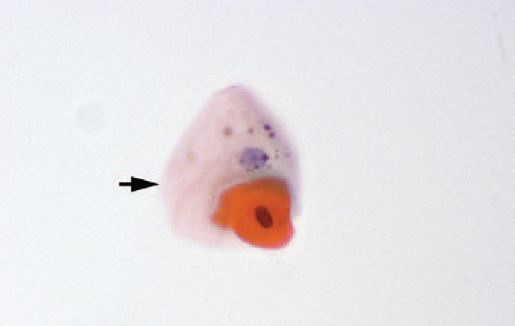

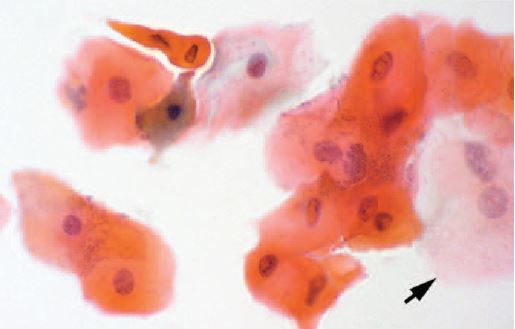

In addition to clinical diagnosis, HBID can also be diagnosed histopathologically. Ocular and oral plaques are distinctively characterized by acanthosis, dyskeratosis, and parakeratosis within the stratified squamous epithelium. The hallmark dyskeratotic cells in hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis have a dense cytoplasm and pyknotic nuclei. Beneath the epithelium in the stroma lies a chronic, mid to moderate lymphocytic inflammatory response. The adjacent stratified squamous epithelium of the conjunctiva can be normal or acanthotic[14][3].

In 1977, Sadeghi and Witkop performed an ultrastructure study using electron microscopy to compare HBID with other disorders of the oral mucosa. They observed that cells in affected HBID patients had a shift in differentiation toward keratinization. Additionally, cells contained densely packed tonofilaments in the cytoplasm, numerous vesicular structures, and disappearance of cellular desmosomes and interdigitations[16].

Diagnostic procedures

Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis is a clinical diagnosis. Plaque biopsy may be performed and sent for histopathologic confirmation.

Genetic testing

Genetic testing is useful for confirmation of HBID but not necessary for diagnosis. In 2001, Allingham and associates were the first to discover a genetic duplication of HBID localized to chromosome 4q35. They studied 2 large families in North Carolina, one of which was originally studied by Carl Witkop, D.D.S[8]. Using slitlamp biomicroscopy, patients were characterized into groups of “definite” HBID, “probable” HBID, “unknown” HBID, and “normal” based upon conjunctival and corneal findings. Subsequently, genotyping was performed with a fluorescent allele static scanning technique (FASST) and PCR. Those who were clinically classified into groups of “definite” and “probable” HBID were found to have a genetic duplication in this region using 2 tightly linked DNA markers, D4S1652 and D4S2390. Of note, a gene was not localized in this region. However, the authors proposed that a candidate gene in this region of duplication could be the human homolog of the FAT gene found in the Drosophilla fly. The FAT gene is a tumor suppressor gene that may promote abnormal epithelial cell proliferation when not functioning properly[8].

In 2008, Cummings et al performed a study on 40 patients revealing that patients with a histopathologic diagnosis of HBID also had a genetic duplication 4q35. In other words, there was a 100% correlation between cytologic and genetic findings in their patient population. This study included one Haliwa-Saponi family and another family from North Carolina[3].

In early 2013, a group in France studied a 7-member French-Caucasian family, two of whom were affected with HBID. However, the signs and symptoms of these two cases were more severe than the classic disease findings previously described[9]. The corneal plaques in these patients were larger and led to severe neovascularization bilaterally, as well as total opacification in one eye. The oral involvement was also more severe and extended to the larynx. Palmoplantar hyperkeratosis was also reported. The investigators performed whole genome sequencing on this 7-member family using negative controls from random post-PRK samples. They found a missense mutation, M77T, in the NLRP1 gene located on chromosome 17p13.2 which is hypothesized to cause destabilization of protein structure. Using quantitative PCR, they also ruled out the duplication 4q35 in the affected patients[9].

Differential diagnosis

Darier-White

|

White Sponge Nevus

|

Hereditary mucoepithelial dyskeratosis

|

Vitamin A deficiency

|

Management

Treatment of HBID has proven to be very difficult and there is no cure to date.

Medical treatment

Medical management with ATs, topical corticosteroids, and systemic immunosuppression only minimally improves the symptoms. Topical management alone has not shown to reduce plaque size in the majority of cases[15][14].

Surgical treatment

A variety of surgical options have been explored, although most are complicated by exuberant recurrence after plaque excision. Excision with beta radiation was attempted by Reed et al, but plaques recurred within 5 weeks and became more visually significant[15]. After penetrating keratoplasty in one patient, the central graft remained clear for 10 months post-operatively, however, mild peripheral plaque recurrence was reported with neovascularization at the graft margin[15]. A study in China by Cai and associates noted one patient to have concurrent HBID and limbal stem cell deficiency. This patient received a limbal allograft in one eye and did not have recurrence after 1.5 years[18]. A patient that received a Prokera device in conjunction with superficial keratectomy experienced an improvement in best corrected visual acuity from counting fingers to 20/200 after 10 months post-operatively[19].

Complications

Surgical excision is often complicated by recurrence of corneal plaques. Plaques that recur may be more extensive, leading to further exacerbation of symptoms and visual impairment[19][18][15].

Prognosis

Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis is a benign disease process with no reported cases of malignant transformation in the literature.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Cummings TJ et al and the College of American Pathologists for permission to use figures from the journal article "Hereditary Benign Intraepithelial Dyskeratosis, an evaluation of diagnostic cytology".

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Von Sallman L, Paton D. Hereditary dyskeratosis of the perilimbal conjunctiva. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1959; 57:53-62.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Witkop CJ et al. Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis. II. Oral manifestations and hereditary transmission. Arch Pathol. 1960 Dec;70:696-711

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Cummings, TJ et al. An Evaluation of Diagnostic Cytology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008 Aug;132(8):1325-8.

- ↑ McLean IW, Riddle PJ, Schruggs JH, Jones DB. Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis. A report of two cases from Texas. Ophthalmology. 1981 Feb;88(2):164-8.

- ↑ Ollague Loaiza W. [Hereditary benign intra-epithelial dyskeratosis (Witkop--Von Sallman syndrome)].

- ↑ Gombos F, Ruocco V, Satriano RA. [Benign hereditary intraepithelial dyskeratosis. Study of a family nucleus]. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1986 Mar-Apr;121(2):97-101. Italian.

- ↑ Dithmar S, Stulting RD, Grossniklaus HE. [Hereditary Benign Intraepithelial Dyskeratosis]. Ophthalmologe. 1998 Oct;95(10):684-6. German.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Allingham, R R et al. A duplication in chromosome 4q35 is associated with hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2001 Feb;68(2):491-4

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Soler, VJ et al. “Whole Exome Sequencing Identifies a Mutation for a Novel Form of Corneal Intraepithelial Dyskeratosis.” Journal of medical genetics 50.4 (2013): 246–54.

- ↑ Baroni, A et al. Hereditary Benign Intraepithelial Dyskeratosis: Case Report. Int J Dermatol. 2009 Jun;48(6):627-9.

- ↑ Jham BC et al. Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis: a new case? J Oral Pathol Med. 2007 Jan;36(1):55-7..

- ↑ Yanoff, M. Hereditary Benign Intraepithelial Dyskeratosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1968 Mar;79(3):291-3.

- ↑ Haisley-Royster CA, Allingham RR, Klintworth GK, Prose NS. Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis: Report of two cases with prominent oral lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001 Oct;45(4):634-6.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Shields CL, Shields JA, Eagle RC Jr. Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987 Mar;105(3):422-3.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Reed JW, Cashwell F, Klintworth GK. Corneal manifestations of hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979 Feb;97(2):297-300.

- ↑ Sadeghi EM, Witkop CJ. Ultrastructural study of hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977 Oct;44(4):567-77.

- ↑ Witkop CJ, Gorlin RJ. Four hereditary mucosal syndromes: comparative histology and exfoliative cytology of Darier-White's disease, hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis, white sponge nevus, and pachyonychia congenita. Arch Dermatol. 1961 Nov;84:762-71.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Cai, R et al. Clinicopathological Features of a Suspected Case of Hereditary Benign Intraepithelial Dyskeratosis with Bilateral Corneas Involved: a Case Report and Mini Review. Cornea 30.12 (2011): 1481–4.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Pachigolla, G et al. Evaluation of the Role of ProKera in the Management of Ocular Surface and Orbital Disorders. Eye Contact Lens. 2009 Jul;35(4):172-5