Gorlin-Goltz syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

- Gorlin-Goltz syndrome Q87.89

- Nevoid Basal-Cell Carcinoma syndrome Q87.89

Introduction

Gorlin and Goltz’s eponymous syndrome, also known as nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), is an autosomal dominant disorder distinguished by multisystemic developmental abnormalities secondary to mutations in the patched-1 (PTCH1) gene. It is estimated to affect an average of 1 in 60,000 people worldwide, with a predilection for Caucasians, but occurs at equal rates between the sexes.[1][2][3]

Genetics

PTCH1 is located on chromosome 9q23.3-q31, and encodes a transmembrane receptor for the ligand sonic hedgehog (SHH).[1] The PTCH1 protein plays a role in both embryonic development and tumor suppression in the hedgehog signaling pathway.[1][4] When unbound by SHH, PTCH1 suppresses the smoothened (SMO) receptor.[5] In the absence of PTCH1 however, SMO becomes constitutively activated, upregulating the hedgehog signaling pathway, and allowing downstream activation of glioma-associated oncogene homologs (GLI1 and GLI2).[5][6] Development of Gorlin-Goltz syndrome has also been linked to mutations in PTCH2 and SUFU.[7] The disease is most commonly inherited with complete penetrance and variable expressivity via a suspected two-hit model in which an inherited mutation in one PTCH1 allele is followed by an acquired loss-of- function mutation in the second allele.[1] Twenty to 40% of patients are estimated to acquire Gorlin-Goltz syndrome by de novo mutations of PTCH1 however.[8]

General Manifestations

Systemic Manifestations

- BCCs are typically non-invasive, and develop between puberty and age 35, with an average age of onset of 25.[1] BCCs of varying number, size, and appearance occur most commonly in sun-exposed areas, and have a higher incidence in western countries, possibly secondary to greater exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation.[1]

- Palmar and plantar pits are permanent, benign, red to dark brown or black papules that appear by age 10 in 30-65% of patients, and are present in more than 85% of patients older than 20 years of age.[1]

- Odontogenic keratocysts are jaw cysts with a characteristic radiographic appearance that are frequently recurrent, and affect 85-90% of patients, appearing as early as 10 years of age.[1]

- Calcification of the falx cerebri, evident on X-ray, increases with age, and affects 65% of patients in the United States, but rarely causes symptoms.[1]

- Skeletal abnormalities include bifid, fused, or markedly splayed ribs in 35% of patients, and kyphoscoliosis in 10-40% of patients.[1]

- Medulloblastoma develops at age 2, earlier than it appears in the general population, and affects 5% of patients.[1]

- Cleft lip and/or palate affects 5% of patients.[4]

Ocular Manifestations

Twenty-six percent of patients develop ocular abnormalities.[5]

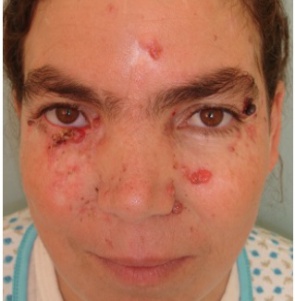

- Periocular BCCs occurs in most patients, have a high rate of recurrence, and may disrupt eyelid architecture.[1][7]

- Hypertelorism, affecting 70% of patients, is an increased distance between the medial canthi that results from enlargement of the sphenoid bone, leading to an abnormal interpupillary distance.[1][7]

- Strabismus, of which esotropia and esophoria may be more prevalent than exotropia and exophoria, occurs in 10-20% of patients.[1][7]

- Myelination of the retinal nerve fibers may occur bilaterally and involve the retina more extensively in Gorlin-Goltz syndrome patients than they do in the general population. This may cause visual field defects or decreased visual acuity.[1][7]

- Eyelid cysts occur in approximately 5-10% of patients.[1][7]

- Microphthalmia affects 1-2% of patients.[1][7]

- Congenital cataracts, sometimes associated with anterior segment dysgenesis, affect 3-8% of patients.[1][7]

- Milia may develop underneath the eyes and around the face in 30% of patients.[7][8]

- Retinal anomalies include retinal detachment, retinal hole, retinal tear, retinoschisis, epiretinal membrane, macular hole, and combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).[1][7]

- Rare ocular manifestations include nystagmus; iris, choroid, and optic nerve colobomas; congenital glaucoma; iris transillumination defects; and subconjunctival epidermoid cysts.[1][7]

Diagnostic Criteria and Procedures

| Table 1: Diagnosis of Gorlin-Goltz syndrome may be established when 2 major, or 1 major and 2 minor criteria are present. |

|---|

| The major criteria are: |

|

| The minor criteria are: |

|

Genetic Testing

Single gene testing for sequence analysis and gene-targeted deletion/duplication analysis of PTCH1 and SUFU genes has become available. Antenatal diagnosis can also be established by DNA analysis of the PTCH1 gene by chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis.[10][11]

Differential Diagnosis

- Muir-Torre syndrome

- Gardner syndrome

- Rombo syndrome

- Bazex syndrome

Management

Surgery

Mohs microsurgical excision is the mainstay of treatment for BCCs. This technique allows for complete removal of lesions whilst preserving the amount of non-involved tissue.

Medical therapy

Medical therapy for Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and BCCs is a trending topic of research, and a variety of therapies have become available in recent years.

Pauwels et al. published an article of 116 patients with BCCs treated with methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy. The patients treated with photodynamic therapy achieved excellent results, and were evaluated for recurrence over the course of 5 years.[12]

In an article by Micali et al., the use of topical chemotherapeutics such as imiquimod is described for the treatment of basocellular lesions. Imiquimod has been used with good results in patients who wish to avoid surgical intervention.[13]

Superficial BCCs without hair follicle involvement are treated by topical use of tretinoin cream and fluorouracil applied to the affected areas twice daily. The use of vitamin A analogues (isotretinoin) or combined oral etretinate has also been suggested.[7]

Novel therapies like vismodegib (Erivedge®) and sonidegib (Odomzo®), are hedgehog gene inhibitors with recent FDA approval for advanced and invasive BCC. Literature of vismodegib being used in patients with Gorlin-Goltz syndrome seems promising with resolution of the keratocystic odontogenic tumors and increase in anti-tumor signaling. Vismodegib significantly reduced the rate of appearance of new surgically eligible BCCs among patients with Gorlin-Goltz syndrome.[6] However, disease recurrence may occur after treatment and thus these novel therapies are primarily reserved for neoadjuvant and/or palliative treatment for locally advanced or invasive periorbital disease. [14]

It is important to note that the behavior of BCCs in patients with Gorlin-Goltz syndrome is different than they are in patients with sporadic malignancies secondary to accumulative UV exposure. Therapies might display different efficaciousness in regards to Gorlin-Goltz syndrome patients compared to the general population.

Prognosis

Life expectancy in Gorlin-Goltz syndrome is not significantly altered, but morbidity from complications can be substantial. Regular follow-up by a multi-specialist team (dermatologist, neurologist and odontologist) should be offered. Patients are advised to avoid excessive sun exposure as well as any form of radiation (X-ray, CT, and radiotherapy) given their intrinsic drive towards developing malignancies.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 Chen JJ, Sartori J, Aakalu VK, Setabutr P. Review of Ocular Manifestations of Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome: What an Ophthalmologist Needs to Know. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22(4):421-7.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Gorlin RJ, Goltz RW. Multiple nevoid basal-cell epithelioma, jaw cysts and bifid rib. A syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1960;262:908–12

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Gorlin RJ. Medicine. Vol. 66. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins Co; 1977. Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome; pp. 97–113

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Larsen AK, Mikkelsen DB, Hertz JM, Bygum A. Manifestations of Gorlin-Goltz syndrome. Dan Med J. 2014;61(5):A4829.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Day A, Abramson AK, Patel M, Warren RB, Menter MA. The spectrum of oculocutaneous disease: Part II. Neoplastic and drug-related causes of oculocutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):821.e1-19.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Booms P, Harth M, Sader R, Ghanaati S. Vismodegib hedgehog-signaling inhibition and treatment of basal cell carcinomas as well as keratocystic odontogenic tumors in Gorlin syndrome. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery. 2015;5(1):14-19. doi:10.4103/2231-0746.161049.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 Jen M, Nallasamy S. Ocular manifestations of genetic skin disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(2):242-75.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Kiwilsza M, Sporniak-tutak K. Gorlin-Goltz syndrome -- a medical condition requiring a multidisciplinary approach. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(9):RA145-53.

- ↑ Evans DG, Farndon PA. Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome. 2002 Jun 20 [Updated 2015 Oct 1]. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2017.

- ↑ Evans DG, Sims DG, Donnai D. Family implications of neonatal Gorlin's syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1991 Oct; 66(10 Spec No):1162-3.

- ↑ Lindström E, Shimokawa T, Toftgård R, Zaphiropoulos PG. PTCH mutations: distribution and analyses. Hum Mutat. 2006 Mar; 27(3):215-9.

- ↑ Pauwels C, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Basset-Seguin N, Livideanu C, Viraben R, Paul C, et al. Topical methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy for management of basal cell carcinomas in patients with basal cell nevus syndrome improves patient's satisfaction and reduces the need for surgical procedures. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011; 25:861

- ↑ Micali G, de Pasquale R, Caltabiano R, Impallomeni R, Lacarrubba F. Topical imiquimod treatment of superficial and nodular basal cell carcinomas in patients affected by basal cell nevus syndrome: a preliminary report. J Dermatolog Treat. 2002; 13:123-7.

- ↑ Sagiv O, Nagarajan P, Ferrarotto R, Kandl TJ, Thakar SD, Glisson BS, Altan M, Esmaeli B. Ocular preservation with neoadjuvant vismodegib in patients with locally advanced periocular basal cell carcinoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019 Jun;103(6):775-780. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-312277. Epub 2018 Jul 18. PMID: 30021814.