Esthesioneuroblastoma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB) is a rare malignant tumor of the upper nasal cavity and anterior skull base first described in 1924 by Berger et al.[1] Local invasion into the orbit, sinuses and central nervous system is common. Signs and symptoms vary and depend on location and degree of invasion. Literature is limited and lack of randomized control trials result in non-standardized treatment methods. However, surgical resection is currently considered gold-standard and often accompanied by adjuvant radiation with a possible role for chemotherapy.

Disease Entity

Disease

There is no ICD-10 specific for Esthesioneuroblastoma, olfactory neuroblastoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, esthesioneuroepithelioma or esthesioneurocytoma. It is currently classified as malignant neoplasm of nasal cavity (ICD-10 C30.0M).

Etiology

Esthesioneuroblastoma is a tumor derived from neural crest cells that arises from the olfactory epithelium lining the sinonasal cavity.[2] It is also referred to as olfactory neuroblastoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, esthesioneuroepithelioma, and esthesioneurocytoma.[3] ENB has an incidence of 0.4 per million and accounts for 3% of all sinonasal malignant tumors.[4][5] Because of its rare occurrence, there is debate amongst grading system, prognosis and clinical management.

Risk Factors

There are no known specific causes or risk factors for ENB. It can affect all age groups but may have a bimodal age distribution between 11-20 and 41-60 years of age.[6] Some reports indicate higher rates in males.[7]

General Pathology

Histological diagnosis is important to rule out ENB versus other sinonasal malignancies, as ENB survival and control rates are much higher compared to non-ENB diagnoses.[8] Typical histology shows a lobular architecture with fibrovascular septae, small round-to-oval blue cells, prominent nuclear membranes, and scant cytoplasm.[9] [10] Homer Wright and Flexner-Wintersteiner rosettes may be present, indicating neuroectodermal origin. Immunohistochemistry stains are necessary for diagnosis. Synaptophysin, chromogranin A, S-100, CD56, neuron specific enolase, and glial fibrillary acidic protein are positive while stains for epithelial, muscle, and lymphoid antigens are generally negative including CK5/6, CK7, CD99, and myogenin.[11] These stains, however, can be weakly positive making a diagnosis of ENB from sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma, lymphoma, and melanoma, among others, challenging.[9][10] Thus, it is necessary to correlate anatomic site, imaging findings, histologic features, and clinical features to make the correct diagnosis.

Diagnosis

History

Diagnosis begins with a thorough history as most patients will have chronic nasal obstruction and congestion refractory to standard medical treatment. Epistaxis is also common.[12] The average delay between appearance of initial symptoms and diagnosis is 6 months as initial symptoms tend to be subtle and frequently found in common nasal diseases such as rhinosinusitis and allergic polypoid sinus disease. [2] Some patient undergo sinus surgery only to have diagnosis unexpectedly established in pathological examination. [2]

Physical Examination

ENB can present in many ways. A patient with a unilateral nasal obstruction or recurrent epistaxis lasting longer than 1-2 months should undergo nasal evaluation by an otolaryngologist. [2] A comprehensive head and neck examination is required as up to 20% of patients may have cervical lymph node metastasis as presentation. [13]

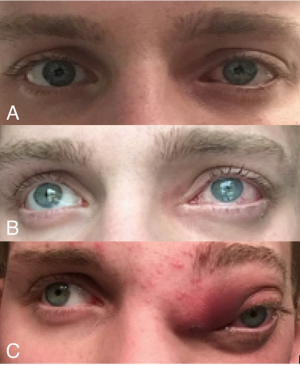

Some studies have shown orbital involvement as high as 73% in ENB cases. [14]In some cases, ophthalmic signs were the earliest presentation of a paranasal sinus tumor. The most common ophthalmic presentation was eyelid edema followed by proptosis, globe injection and ptosis. [14] Thus it is important for ophthalmologist to have a high clinical suspicion for paranasal sinus tumors when evaluating a patient with orbital findings, specially if review of systems are positive for concurrent sinus symptoms. In these cases, a full eye exam including vision, motility, intraocular pressure and fundoscopy is warranted which can help determine orbital involvement.

Signs and Symptoms

Clinically, symptoms depend on location and extent of the tumor. Initially, most symptoms tend to be those found in common nasal diseases such as congestion and obstruction. As the tumor grows, symptoms worsen depending on location and extent of disease. It is common to have local invasion into the orbit, sinuses and intracranial cavity through erosion of the cribriform plate. Worsening sinus invasion commonly causes facial pain and epistaxis, a symptom often indicating a malignant process. Extension into the orbit can cause injection, ptosis, diplopia, proptosis, decreased vision and epiphora. Intracranial extension can present with headaches, seizures and neurologic complications.

Disease Staging

Multiple staging systems exist to predict prognosis in ENB.

The Hyams system divides the spectrum of disease into four histopathologic grades, ranging from most differentiated (grade I), to least differentiated (grade IV), based on features such as tumor architecture, mitotic activity, nuclear polymorphism and presence of necrosis. [15]

The Kadash staging system grades tumors based on their extent of spread, and has been shown to correlate with disease-free survival time. [12]

- Group A: limited to nasal cavity

- Group B: extend to the paranasal sinus

- Group C: extend beyond the paranasal sinus (including the orbit)

Dulguerov also devised a TNM system for ENB, to include nodal status. [16]

Diagnostic procedures

Nasal endoscopy is helpful for tumor characterization, localization and biopsy.[13] On endoscopy, ENB is usually seen as a reddish-gray tumor arising in the upper nasal fossa which bleeds easily with instrumentation.[2] Biopsy via endoscopy is less invasive and helpful for surgical planning.

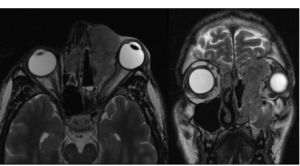

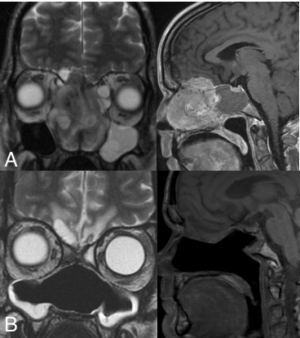

Computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are required for staging; CT provides information on bony erosion and MRI provides more accurate detail of soft tissue invasion. [10] ENB lacks a specific radiologic appearance and is seen as a homogenous soft tissue mass in the upper nasal cavity occupying the ethmoid air cells. Invasion of the cribriform plate and medial orbital walls is common and can help stage disease. [2]

Laboratory test

There is no laboratory test for ENB. Immunohistochemical stain can help differentiate ENB from other tumors with similar histological features on light microscopy.

Differential diagnosis

The differential for ENB is wide and depends on presenting features. Imaging showing a midline sinonasal tumor, particularly with orbital and CNS involvement in correlation with clinical signs and symptoms can be very suggestive of ENB. However, with orbital invasion, tumors such as rhambdomyosarcoma, cavernous hemangioma, hemangiopericytoma and lymphatic/vascular malformations can have overlapping features. With predominant sinus invasion, benign and malignant masses such as schneiderian papilloma, antrochoanal polyp, angiofibroma, encephaloceles, squamous cell carcinoma and nasal lymphomas may also be considered.

Management

General treatment

Treatment for ENB consists of a multi-disciplinary team including a head and neck surgeon, medical and radiation oncologist, primary care physician and other specialists such as neurosurgery and oculoplastics as needed. [13] Treatment approach depends on tumor stage and whether or not there is metastatic disease. [13] Literature for ENB is limited and lack of randomized control trials result in non-standardized treatment methods.

Medical therapy

The use of chemotherapy remains more controversial. A combination of cisplatin and etoposide appears to be the most common chemotherapeutic regimen for ENB, translated from early clinical trials on neuroectodermal tumors such as medulloblastoma.[17] [18] Although no clear consensus exists on when chemotherapy should be used, some published papers advocate for chemotherapy use in all cases to improve local control. [10][18][17][19] Systematic reviews indicate that chemotherapy with surgery and/or radiation has better survival benefits than mono therapy or no treatment. [20]

Medical follow up

Medical follow-up consists of a multidisciplinary team. Surveillance imaging is required as recurrence is common. In addition, there is a lifelong risk of lymph node metastasis so frequent clinical exams are important. Post-surgical patients often experience chronic symptoms of nasal congestion and obstruction which require regular sinus irrigation, debridement and topical therapy.

Surgery

Studies suggest that surgery alone is best for small tumors localized to the sinonasal cavity without involvement of the skull base or orbit. For more advanced tumors, studies show that surgery with postoperative radiotherapy have the highest overall survival. [3][10][13][21][22][23] Preoperative radiation and induction chemotherapy are often commonly utilized.[12]

The traditional approach for surgery has been the open craniofacial resection which usually consists of a frontal craniotomy. Recently, less invasive surgical approaches using endoscopic resection have become increasingly utilized. A combination of both, involving endoscopic-assisted cranionasal resection, has also gained popularity, particularly for larger tumors requiring both neurosurgeons and head and neck surgeons.

Surgical follow up

Esthesioneuroblastoma requires lifelong surveillance for recurrence and metastasis. Most surgeons obtain regular imaging such as CT/MRI and PET scan to help monitor disease progression.

Prognosis

Prognosis for each stage is inconsistent among studies, likely because of the rarity of ENB and because much available literature is compromised of smaller retrospective institutional studies. However, stage at presentation has been shown to be highly predictive of survival, although no universally accepted staging system exists.[10] The three most popular staging systems are Kadish, Dulguerov, and Hyams. Kadish staging takes into account local disease extent and a more recent modified staging system includes nodal and metastatic spread.[24] Dulguerov uses tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging which evaluates tumor local spread to the sinuses, orbit, or brain, cervical lymph node metastasis, and distant metastasis.[24] Hyams uses a histological grading system to evaluate the biology of the tumor and its locoregional aggressiveness.[3] Kadish staging does seem to be more commonly used in published literature. Although no single staging system appears to be consistently reliable, all are valuable for clinical decision making. Size of the tumor, location of extension, and histologic grading of tumor aggressiveness can all help stratify between low and high-risk cases to personalize management for each case.

A large analysis of 390 patients showed a 5-year survival rate of 72% in Kadish A tumor, 59% in Kadish B tumors and 47% in Kadish C tumors.[25] Other smaller studies report higher survival while some have not found a survival correlation based on kadish staging. [26][27]

Another recent analysis of 1,167 patients with esthesioneuroblastoma identified from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) also looked to determine 5-year survival rates based on the Kadish grading system. In this study, 5-year survival rates were 80.0% for Kadish stage A, 87.7% for Kadish stage B, 77.0% for Kadish stage C, and 49.5% for Kadish stage D.

As you can see, the rarity of this disease makes it difficult to validate a staging system and determine consistent prognostic values amongst large and small studies. [28]

Because recurrence can occur after 5 or even 10 years, long-term follow-up is mandatory.[29]

Acknowledgments

All Images are courtesy of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

References

- ↑ Berger L, Luc R, Richard D. Olfactory neuroblastoma. Bull Assoc Fr Etude Cancer. 1924; 13: 410–42.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/278047-overview

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 Saade, R. E., Hanna, E. Y., Bell, D. (2014). Prognosis and Biology in Esthesioneuroblastoma: the Emerging Role of Hyams Grading System. Current Oncology Reports, 17(1).

- ↑ Theilgaard SA, Buchwald C, Ingeholm P et al (2003) Esthesio-neuroblastoma: a Danish demographic study of 40 patientsregistered between 1978 and 2000. Acta Otolaryngol 123:433–439

- ↑ Diaz EM Jr, Johnigan III RH, Pero C, et al. Olfactory neuroblastoma: the 22-year experience at one comprehensive cancer center. Head Neck 2005;27:138–149.

- ↑ Fiani B, Quadri SA, Cathel A, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: A Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis, Management, and Current Treatment Options. World Neurosurg. 2019;126:194–211. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.03.014

- ↑ Woods RSR, Subramaniam T, Leader M, et al. Changing Trends in the Management of Esthesioneuroblastoma: Irish and International Perspectives. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2018;79(3):262‐268. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1607298

- ↑ Rosenthal DI, Barker JL, El-Naggar AK, Glisson BS, Kies MS,Diaz EM, et al. Sinonasal malignancies with neuroendocrine dif-ferentiation. Cancer. 2004;101(11):2567–73

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Charles, N. C., Petris, C. K., & Kim, E. T. (2016). Aggressive esthesioneuroblastoma with divergent differentiation: A taxonomic dilemma. Orbit, 35(6), 357–359.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Rimmer, J., Lund, V. J., Beale, T., Wei, W. I., & Howard, D. (2014). Olfactory neuroblastoma: A 35-year experience and suggested follow-up protocol. The Laryngoscope, 124(7), 1542–1549.

- ↑ Thompson, L. Small round blue cell tumors of the sinonasal tract: a differential diagnosis approach. Mod Pathol : 30, S1–S26 (2017).

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 Limaiem F, Das JM. Esthesioneuroblastoma. Stat Pearls. Online. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539694/

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 https://med.uth.edu/orl/2012/09/07/esthesioneuroblastoma/

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Rakes SM, Yeatts RP, Campbell RJ. Ophthalmic manifestations of esthesioneuroblastoma. Ophthalmology. 1985;92(12):1749‐1753. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34102-7

- ↑ Saade, R.E., Hanna, E.Y. & Bell, D. Prognosis and Biology in Esthesioneuroblastoma: the Emerging Role of Hyams Grading System. Curr Oncol Rep 17, 423 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-014-0423-z

- ↑ Dulguerov P, Allal AS, Calcaterra TC. Esthesioneuroblastoma: a meta-analysis and review. Lancet Oncol. 2001 Nov;2(11):683-90.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Fitzek, M. M., Thornton, A. F., Varvares, M., Ancukiewicz, M., Mcintyre, J., Adams, J., Rosenthal, S., Joseph, M., Amrein, P. (2002). Neuroendocrine tumors of the sinonasal tract: Results of a prospective study incorporating chemotherapy, surgery, and combined proton‐photon radiotherapy. Cancer, 94(10), 2623-2634.

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 Sawamura, Y., Ikeda, J., Ishii, N., Kato, T., Tada, M., Abe, H., & Shirato, H. (1996). Combined Irradiation and Chemotherapy Using Ifosfamide, Cisplatin, and Etoposide for Children with Medulloblastoma/Posterior Fossa Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor—Results of a Pilot Study—. Neurologia medico-chirurgica, 36(9), 632-638.

- ↑ Polin RS, Sheehan JP, Chenelle AG, et al. The role of preoperative adjuvant treatment in the management of esthesioneuroblastoma: the University of Virginia experience. Neurosurgery 1998; 42: 1029–1037.

- ↑ Marinelli JP, Janus JR, Van Gompel JJ, Link MJ, Foote RL, Lohse CM, Price KA, Chintakuntlawar AV. Ethesioneuroblastoma with distance metastases: systematic review & meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2018;40(10):2295-2303.

- ↑ Lund VJ, Howard D, Wei W, Spittle M. Olfactory neuroblastoma: past, present, and future. Laryngoscope 2003; 113: 502–507.

- ↑ Song, X., Wang, J., Wang, S., Yan, L., Li, Y. (2020). Prognostic factors and outcomes of multimodality treatment in olfactory neuroblastoma. Oral Oncology, 103, 104618.

- ↑ Dulguerov, P., Allal, A. S., Calcaterra, T. C. (2001). Esthesioneuroblastoma: a meta-analysis and review. The Lancet Oncology, 2(11), 683–690.

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 Bachar G, Goldstein DP, Shah M, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: the Princess Margaret Hospital experience. Head Neck.2008;30:1607–14.

- ↑ Dulguerov P, Allal AS, Calcaterra TC. Esthesioneuroblastoma: a meta-analysis and review. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2(11):683–690.

- ↑ Dulguerov P, Calcaterra T. Esthesioneuroblastoma: the UCLA experience 1970-1990. Laryngoscope. 1992;102(8):843–849.

- ↑ McLean JN, Nunley SR, Klass C, Moore C, Müller S, Johnstone PA. Combined modality therapy of esthesioneuroblastoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(6):998–1002

- ↑ Konuthula N, Iloreta AM, Miles B, et al. Prognostic significance of Kadish staging in esthesioneuroblastoma: An analysis of the National Cancer Database. Head Neck. 2017;39(10):1962‐1968. doi:10.1002/hed.24770

- ↑ Morita A, Ebersold M, Olsen K, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: Prognosis and management. Neurosurgery.1993;32: 706-714