Diagnostic Approach to Atypical Optic Neuritis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Optic neuropathy is a non-specific term characterized by dysfunction of the optic nerve. The clinical findings include variable loss of visual acuity or visual field, dyschromatopsia, a relative afferent pupillary defect in unilateral or bilateral but asymmetric cases, and a swollen, pale, or normal (initially) optic nerve. The differential diagnosis for optic neuropathy is broad and includes demyelination, inflammation, trauma, ischemia, compression, autoimmune diseases, genetics, and/or toxins [1][2]. The acute inflammatory or demyelinating form of optic neuropathy that involves one or both optic nerves is termed optic neuritis (ON). The most common type of ON is labeled “typical”, or “demyelinating ON”, which may be associated with multiple sclerosis (MS) or may be idiopathic [3].

With typical ON, there is a classical triad of symptoms:

- Variable vision loss (visual acuity or visual field)

- Periocular pain (worse with eye movement)

- Dyschromatopsia

Patients with typical ON generally have a favorable prognosis with good visual recovery regardless of treatment [4]. In contrast, lack of visual recovery is a marker of “atypical” ON. This “atypical” ON can be caused by a heterogeneous collection of disorders including neuromyelitis optica (NMO), autoimmune optic neuropathy, chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), idiopathic recurrent neuroretinitis, and optic neuropathy from systemic disease [5]. If left untreated, atypical ON can lead to devastating visual results; therefore, it is crucial to recognize, initiate proper treatment, and preserve vision for patients with atypical ON.

Risk Factors and Epidemiology

Typical demyelinating or idiopathic ON commonly affects young white women, with a reported female-to-male ratio of 5:1, and an age range of 20-40 years old [6]. Furthermore, MS associated-ON is highest in people living in higher altitudes and reduces significantly when closer to the equator with some theories attributing this difference to vitamin D and sunlight exposure [4]. Atypical ON deviates away from this demographic and often includes males, with onset at age less than 18 or greater than 50 years old [3]. In the United States of America, studies have estimated the annual incidence of ON as 5 per 100,000 [4].

Etiology

Although ON is commonly idiopathic it can be related to the following [4]:

- Demyelination (e.g., MS)

- Antibody mediated (e.g., NMO, MOG)

- Inflammatory autoimmune (e.g., Sarcoidosis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Sjogren Syndrome, and Bechet Disease)

- Infectious (e.g., Herpes Zoster, Lyme Disease, Syphilis, Tuberculosis, Dengue, mumps, and West Nile Virus, Tuberculosis, Hepatitis B, Rabies, Tetanus, Meningitis, Anthrax, Measles, Rubella.)

- Post-infectious/post-vaccination

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

| Typical Optic Neuritis | Atypical Optic Neuritis |

| Unilateral loss of visual acuity | Bilateral loss of visual acuity |

| Periocular pain (90%) worse with eye movement | Can be painless, painful, or persistent pain > 2 weeks |

| Predominantly female | Male |

| Age range of onset 20-40 years old | Age of onset <18 or >50 years old |

Clinical findings include:

|

Abnormal ocular findings including:

|

| Spontaneous visual improvement (>90%) | Pronounced vision loss > 2 weeks with absence of any visual recovery within 3-5 weeks |

| Previous history of ON or MS | Systemic diseases other than MS |

Physical Examination

A complete dilated eye examination is recommended including formal automated perimetry for all patients with suspected ON [1][3][7]. The Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial (ONTT) was a randomized, controlled clinical trial that defined the treatment for ON [7]. In the ONTT, testing for etiologies other than MS was not helpful in typical ON. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) however was helpful in defining the risk for MS. Patients suspected of having an infectious, inflammatory, or autoimmune etiology for ON however based upon atypical features in the history or examination may benefit from further testing. Slit lamp biomicroscopy for anterior segment inflammation (uveitis) and posterior segment evaluation for vitreous cells and posterior uveitis is recommended [3].

Diagnostic Procedures

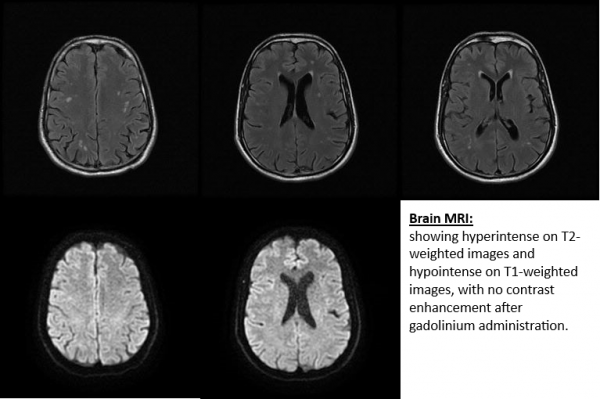

Brain and orbital MRI with contrast can confirm or exclude different forms of optic neuropathy. Typical ON demonstrates a short segment of contrast enhancement of the optic nerve and demyelinating white matter lesions for MS may be seen. Even in the absence of typical demyelinating white matter lesions at onset, patients with ON may still develop MS [4]. MS lesions on MRI are characteristically hyperintense on T2 weighted imaging, ovoid, and located in the periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial, and spinal cord white matter [3]. Atypical ON due to NMO may show a non-MS location of white matter lesions on the brain MRI, the optic nerve enhancement may be more posterior (optic chiasm and optic tract) and there maybe longitudinally extensive enhancement (> ½ length) of the optic nerve. In addition, patients with spinal MRI may show a longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (greater than 3 spinal segments) [3]. Therefore, MRI can be a useful tool to differentiate between different etiologies of ON.

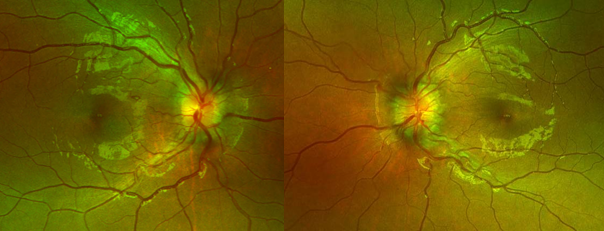

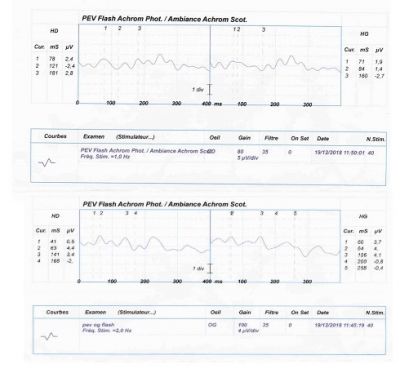

Optic Coherence Tomography (OCT) is a non-invasive imaging tool that can measure the thickness of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer in ON [3][8]. OCT can be used to assess thickening or thinning of the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer at different stages of ON [8]. Visual evoked potential (VEP) is an electrophysiologic test that can measure electrical signals in response to visual stimuli [3]. Damage along the afferent visual pathway can result in diminished speed or amplitude of the VEP waveform. The P100 latency is the first positive waveform peak and an increased latency can be suggestive of ON [3].

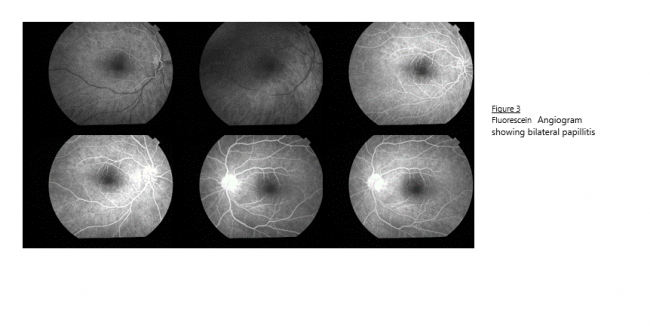

Finally, fluorescein angiography can be performed to determine is there is leakage of the optic disc, macular edema or retinal vessels abnormalities.

Laboratory Testing

In the ONTT, additional laboratory testing (e.g., erythrocyte sedimentation rate or antinuclear antibodies, syphilis serology) were unlikely to demonstrate any true positive results in typical ON. Patients with atypical ON may benefit form additional testing. Some additional tests that might be considered include aquaporin-4 water (AQP4) antibodies or MOG antibodies [3].

| Typical Optic Neuritis | Atypical Optic Neuritis |

| Humphrey Visual Field Testing | Humphrey Visual Field Testing |

| MRI | MRI |

| - | Lumbar Puncture |

| - | MOG Antibodies |

| - | AQP4 Antibodies (NMO) |

| - | ACE, lysozyme, chest X-ray for sarcoid |

| - | Treponemal and non-treponemal syphilis tests |

| - | Blood testing (ESR, CRP, CBC) |

| - | Chest X-ray |

| - | Other testing as it relates to your differential diagnosis (e.g., Lyme, Tuberculosis, Bartonella, etc.) |

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of ON includes demyelinating, infiltrative, neoplastic, inflammatory, traumatic, hereditary, and infectious etiologies.

Treatment and Management of Atypical Optic Neuritis

In the ONTT, patients recovered vision with or without steroids. Oral steroids in conventional doses however increased the rate of new attacks and are not recommended. Although intravenous (IV) steroids sped the rate of recovery in typical ON, the final visual outcome was the same in all three treatment arms of the ONTT (oral steroids, IV steroids, or placebo). Atypical ON however should undergo full testing for alternative etiologies as above for an optic neuropathy and treatment should be directed to the underlying etiology.

For atypical ON, corticosteroids are frequently given in the acute phase until the testing can be completed. Patients who do not respond to initial IV steroid therapy (e.g., NMO or MOG) may benefit from early plasma exchange (PLEX) or IVIG.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the underlying etiology. As noted above, the visual loss in typical ON usually recovers and the most common etiology is MS. In atypical ON however the prognosis depends upon the underlying etiology.

Summary Statement

Clinicians should be aware of the clinical features of an optic neuropathy. Typical ON is characterized by an acute, unilateral, loss of visual acuity or visual field, pain with eye movement, an ipsilateral relative afferent pupillary defect, and a normal optic nerve (retrobulbar ON) in approximately two-third of cases. Patients with bilateral visual loss, a painless presentation, or a severe swollen optic nerve are features of atypical ON. Cranial and orbital MRI demonstrates a short segment of enhancement of the optic nerve in typical ON and may show demyelinating white matter lesions in cases secondary to MS. Atypical radiographic presentations for ON include longitudinally extensive enhancement of the optic nerve, posterior involvement (optic chiasm or optic tract) or bilateral involvement. In addition, enhancement of the optic sheath or the orbital fat is atypical for demyelinating or idiopathic ON. Treatment with IV steroids speeds the rate of recovery in typical ON but does not change final visual outcome but oral steroids in conventional doses may increase the rate of ON recurrence. Patients with atypical ON however should be considered for IV steroids and may require PLEX (e.g., NMO).

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Guier CP, Stokkermans TJ. Optic Neuritis. [Updated 2021 Feb 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557853/

- ↑ Behbehani R. Clinical approach to optic neuropathies. Clin Ophthalmol. 2007;1(3):233-246.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Abel A, McClelland C, Lee MS. Critical review: typical and atypical optic neuritis. Survey of ophthalmology. 2019 Nov 1;64(6):770-9.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Hoorbakht H, Bagherkashi F. Optic neuritis, its differential diagnosis and management. The open ophthalmology journal. 2012;6:65.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Malik A, Ahmed M, Golnik K. Treatment options for atypical optic neuritis. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2014 Oct;62(10):982.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Kaur K, Gurnani B, Devy N. Atypical optic neuritis–a case with a new surprise every visit. GMS ophthalmology cases. 2020;10.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Newman JN. The Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Ophthalmology. Volume 127, ISSUE 4, SUPPLEMENT, S172-S173, April 01, 2020

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Adhi M, Duker JS. Optical coherence tomography--current and future applications. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013;24(3):213-221. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e32835f8bf8