Cushing’s Syndrome of the Orbit

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome of the orbit – also known as corticosteroid induced exophthalmos, Cushing’s exophthalmos, steroid exophthalmos, steroid proptosis, or steroid orbitopathy – is a disease process associated with iatrogenic systemic steroid exposure. Cases have been reported with endogenous steroids in the setting of true Cushing’s disease, and there is overlap in the presenting signs, symptoms, and treatment options for each etiology.

This article emphasizes features and cases of iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome of the orbit. Cushing’s of the orbit can present with a constellation of systemic and ocular signs, with exophthalmos being the most common presenting sign and progression to vision-threatening compressive optic neuropathy and globe subluxation reported.1-10 Steroid-induced exophthalmos can both radiographically and clinically mimic a malignant or inflammatory process and is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion. Treatment options largely depend on the severity of signs and symptoms, and successful treatment correlates with steroid cessation if possible. It is important to remind medical practitioners of this potentially vision-threatening complication of systemic corticosteroids.

Etiology

Orbital Cushing’s syndrome is associated with significant systemic corticosteroid exposure.7

Epidemiology

- No age or gender preference.

- The most significant epidemiological factor is the dose and duration of endogenous or exogenous steroid intake.

- Implicated exogenous steroids include hydrocortisone, prednisone, and methylprednisolone, in pill or intravenous formulations, ranging from 6 months to more than 21 years of steroid use prior to steroid orbitopathy diagnosis.1-10

- A total of 51 published cases of iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome of the orbit have been found prior to 2020. The majority of those cases were published prior to 1997. Only 5 cases have been found in literature between 1997-2023. These latter cases demonstrated more severe pathology than the majority of previously published cases.

Risk Factors

Anything involving increased systemic corticosteroid exposure can be considered a potential risk factor. This includes but is not limited to systemic steroids for asthma control, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations, pneumonitis after radiation for lung cancer, adrenocortical insufficiency, and treatment for myasthenia gravis.8,9 Patients with true Cushing’s disease from a pituitary adenoma that leads to excess cortisol production from the adrenal glands are also at risk of developing Cushing’s syndrome of the orbit.11,12

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of orbital Cushing’s syndrome is unclear. Experimental work in animal models has shown that exogenously administered steroids can reproducibly induce exophthalmos.2,3 It has been suggested that corticosteroids promote changes in glucocorticoid receptor binding, lipoprotein lipase activity, and redistribution of facial and orbital adipose tissue.2,3,7 It is unknown whether the changes in retro-orbital fat are related to fat expansion or differential fat deposition as seen elsewhere in the body with Cushing’s syndrome.3,13

Diagnosis

History

Steroid-induced exophthalmos was first described in 1958 in a case of Cushing’s syndrome that first manifested as exophthalmos, and initial reports purported this to be a benign disease.1-6,13,14 Since then, exophthalmos secondary to iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome has been infrequently reported, with a decrease in reports perhaps attributable to the rise of steroid-sparing immunotherapies. However, more recent case reports display worse pathology8-10 and suggest recognition of this disease entity and diagnosis may be delayed.

Physical Examination

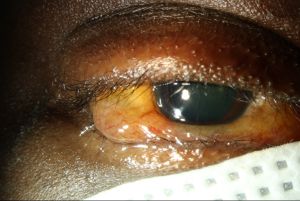

Cushing's syndrome is a known complication of systemic corticosteroids, and classically presents with cushingoid features including but not limited to increased fat deposits in the upper half of the body, thin arms and legs, acne, hirsutism, proximal muscle weakness and paper-thin skin.15 Patients with orbital involvement may display exophthalmos, periorbital soft tissue swelling, resistance to retropulsion, eyelid edema, chemosis (Figure 1), conjunctival injection, ocular hypertension, cataracts, serous retinal detachments, and globe subluxation.9,16,17 Advanced cases may show signs of congestive orbitopathy such as a relative afferent pupillary defect, constricted visual field, limitation of extraocular movements, or optic nerve dysfunction.1-9,11,18

Signs and Symptoms

The patient may report foreign body sensation, lacrimation, photophobia, orbital pain, redness, and proptosis. More advanced cases may be characterized by double vision, globe subluxation, and symptoms suggestive of compressive optic neuropathy including progressive vision loss or color desaturation.

Workup

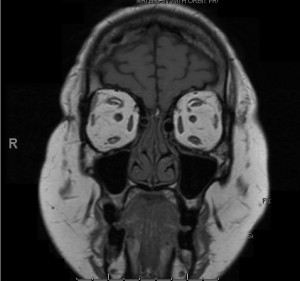

Patients should undergo neuroimaging, which would classically show only expansion of the retro-orbital fat in patients with iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome of the orbit. This is in contrast to patients with endogenous steroids from Cushing’s disease, which would be expected to show a pituitary abnormality in addition to the retro-orbital fat expansion. This retro-orbital fat expansion differs from other common causes of congestive orbitopathies, such as thyroid eye disease (TED), where muscle bellies are often enlarged while tendons are spared. In cases of non-specific orbital inflammation (NSOI), both muscle bellies and tendons may show enlargement. IgG4 disease classically demonstrates enlarged infraorbital canals, while changes in signal intensity could suggest other inflammatory or neoplastic processes.

Although history and exam alone could support a diagnosis of orbital Cushing’s syndrome, the overlap of signs and symptoms with potentially devastating disease processes may warrant further evaluation with laboratory testing and biopsy.

Laboratory studies include neoplastic, inflammatory, and infectious labs such as a complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI), rheumatoid factor, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), immunoglobulin subclasses, treponemal immunoglobulin, and tuberculosis testing. Laboratory workup should be within normal limits, though abnormalities related to chronic steroid use may be seen (such as low TSH, for example).

Biopsy of the expanded orbital fat compartment should yield essentially normal fat or fibroadipose tissue without inflammatory or atypical cellular infiltrates.

Differential Diagnosis

- Thyroid eye disease

- Non-specific orbital inflammation

- Xanthogranulomatous disease

- IgG4 - related ophthalmic disease

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Lymphoproliferative disease

- Neoplastic lesion

- Metastatic disease

- Vascular malformation

- Orbital cellulitis (bacterial or fungal)

Management

Educating healthcare providers about this rare but potentially vision-threatening side effect of systemic steroids is mandatory. In addition, recognizing this diagnosis is crucial, as it can mimic orbital inflammatory conditions often treated with steroids as first-line therapy. In such cases, systemic steroids could exacerbate the disease and hasten sight-threatening sequelae.

Medical management from an ophthalmic perspective may temporize symptoms and can include artificial tears or lubricating eye ointment for comfort and protection of the ocular surface. Ocular anti-hypertensives may be indicated for elevated intraocular pressure.

For patients with exogenous steroid use, discontinuing systemic steroid products is recommended if feasible due to the link between steroid exposure and disease manifestation. Transitioning patients to targeted immunomodulatory therapies should be considered. For patients with endogenous steroids from a pituitary tumor, neurosurgery and endocrinology are required for management.

If vision-threatening sequelae are present, or if the degree of exophthalmos results to an unacceptable appearance or ocular surface issues, surgery may be considered. Exophthalmos, globe subluxation, congestive orbitopathy with elevated intraocular pressure, and optic neuropathy can be promptly improved through surgical orbital decompression. Orbital decompression can include the medial wall, the deep lateral wall, and the orbital floor (including the palatine process). Most importantly, concurrent fat decompression is strongly encouraged, as this not only provides significant orbital volume reduction but also reduces the substrate for expansion in the future.

References

1. Boschi A, Detry M, Duprez T, et al. Malignant bilateral exophthalmos and secondary glaucoma in iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. Apr 1997;28(4):318-20.

2. Katz B, Carmody R. Exophthalmos induced by exogenous steroids. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. Dec 1986;6(4):250-3.

3. Panzer SW, Patrinely JR, Wilson HK. Exophthalmos and iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. Dec 1994;10(4):278-82. doi:10.1097/00002341-199412000-00012

4. Slansky HH, Kolbert G, Gartner S. Exophathalmos induced by steroids. Arch Ophthalmol. May 1967;77(5):578-81. doi:10.1001/archopht.1967.00980020581003

5. Cohen BA, Som PM, Haffner PH, Friedman AH. Case report. Steroid exophthalmos. J Comput Assist Tomogr. Dec 1981;5(6):907-8. doi:10.1097/00004728-198112000-00024

6. Van Dalen JT, Sherman MD. Corticosteroid-induced exophthalmos. Doc Ophthalmol. Aug 1989;72(3-4):273-7. doi:10.1007/bf00153494

7. Blendea MC, Lock JP. Visual vignette. Steroid-induced exophthalmos. Endocr Pract. Jan-Feb 2011;17(1):153. doi:10.4158/ep10190.Vv

8. Dam J, Marcuse F, De Baets M, Cassiman C. Globe Subluxation following Long-Term High-Dose Steroid Treatment for Myasthenia Gravis. Case Rep Ophthalmol. Sep-Dec 2020;11(3):534-539. doi:10.1159/000509527

9. Ortega-Evangelio L, Navarrete-Sanchis J, Williams BK, Jr., Tomas-Torrent JM. Spontaneous globe luxation in iatrogenic Cushing syndrome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. Oct 2015;253(10):1809-11. doi:10.1007/s00417-015-3126-8

10. Ekeh L, Ibrahim H, Askar F, Meysami A, Simmons BA. Cushing's syndrome of the orbit: congestive orbitopathy and optic neuropathy associated with steroids. Orbit. Oct 19 2023:1-4. doi:10.1080/01676830.2023.2268158

11. Giugni AS, Mani S, Kannan S, Hatipoglu B. Exophthalmos: A Forgotten Clinical Sign of Cushing's Syndrome. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2013;2013:205208. doi:10.1155/2013/205208

12. Cushing H. The basophil adenomas of the pituitary body and their clinical manifestations (pituitary basophilism). 1932. Obes Res. Sep 1994;2(5):486-508. doi:10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00097.x

13. Kelly W. Exophthalmos in Cushing's syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). Aug 1996;45(2):167-70. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.d01-1559.x

14. Peyster RG, Ginsberg F, Silber JH, Adler LP. Exophthalmos caused by excessive fat: CT volumetric analysis and differential diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. Mar 1986;146(3):459-64. doi:10.2214/ajr.146.3.459

15. Schäcke H, Döcke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther. Oct 2002;96(1):23-43. doi:10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00297-8

16. Loo JL, Lee SY, Ang CL. Can long-term corticosteriods lead to blindness? A case series of central serous chorioretinopathy induced by corticosteroids. Ann Acad Med Singap. Jul 2006;35(7):496-9.

17. Phulke S, Kaushik S, Kaur S, Pandav SS. Steroid-induced Glaucoma: An Avoidable Irreversible Blindness. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. May-Aug 2017;11(2):67-72. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-l0028-1226

18. Morgan DC, Mason AS. Exophthalmos in Cushing's syndrome. Br Med J. Aug 23 1958;2(5094):481-3. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5094.481