Corneal Allograft Rejection and Failure

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

In uncomplicated or "low risk” penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) primary grafts, the survival rate with local immune suppression has been reported to be as high as 95% at 5 years [1]. This remarkable degree of success is achieved by the “immune privileged” status of the cornea, which is caused by an aggregate of factors including [2]:

- Absence of vascularity that hinders delivery of immune elements

- Absence of corneal lymphatics that prevents delivery of antigens to T cells in lymph nodes

- Expression of FAS ligand that can induce apoptosis of stimulated Fas+T cells

- An unusually low expression of MHC antigens

- A unique spectrum of immunomodulatory factors that inhibit T cell and complement activation

In contrast, “high-risk” recipients, such as those with vascularization of the cornea, the failure rate can easily exceed 35% at three years [3]. Despite being an “immunologically privileged” site, the most common cause of graft failure is irreversible, immunologic allograft rejection.

One of the major advantages of deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) over PKP is the elimination of the risk of endothelial rejection, although subepithelial and stromal rejection can still occur. Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) and Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) have revolutionized corneal transplantation and has decreased the risk of graft rejection due to less foreign tissue being transplanted.

Definition of graft rejection vs failure:

The term graft rejection refers to a specific immunologic response of the host to the donor corneal tissue. It should be distinguished from other non-immune mediated graft failures, such as primary donor failure. Primary donor graft failure is defined as cornea edema that never clears from the immediate postoperative period secondary to inherent deficiencies in the donor graft, surgical trauma, or improperly stored tissue.[4] It is advised by the Eye Bank Association of America that ideal donor corneas should have at least 2000 cell/mm2 and be stored for less than 7 days.[5] Diagnosis of rejection should only be made in grafts that have remained clear for at least 2 weeks following surgery. The incidence of rejection is greatest in the first year-and-a-half following transplant but can occur up to 20 years or more after surgery. Guilbert et al reported an average keratoplasty-to-rejection time of 19.8 ± 20.4 months (among 299 patients who experienced a rejection episode). The progression from rejection to failure was 49% [6].

Diagnosis:

Clinical signs of graft rejection (from most to least common) include:

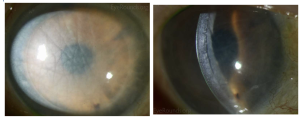

- Corneal edema

- Keratic precipitates (KPs) on the corneal graft but not on the peripheral recipient cornea

- Corneal vascularization

- Stromal infiltrates

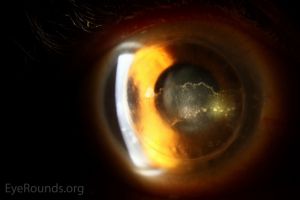

- A Khodadoust line

- An epithelial rejection line

- Subepithelial infiltrates

A Khodadoust line separates immunologically damaged endothelium from unaffected endothelium. In the area of damage, the endothelium is decompensated resulting in stromal and epithelial edema. The diagnosis of immunologic graft failure is made if signs of rejection do not clear within 2 months of treatment.

Risk Factors

For penetrating keratoplasty (PKP), risk factors for rejection include:[4]

- Preoperative inflammation

- Corneal neovascularization (> 2 quadrants)

- Young recipient age

- Iris synechiae to the graft margin

- Large grafts

- History of inflammatory disease

- Prior ocular surgery

- Loose sutures

- Prior graft rejection

- Prior use of glaucoma medications or surgery

For DSEK, risk factors for rejection include:[7]

- African- American race

- Pre-existing glaucoma

- Steroid- responsive intraocular pressure

Herpetic infection and corneal allograft rejection have been associated and hypothesized to occur either simultaneously or synergistically. One study demonstrated that positive PCR tests for herpes viruses was significantly greater in eyes that presented with clinical corneal endothelial allograft rejection (AGR).[8]

Immune rejection:

There are several forms of immune rejection including epithelial, subepithelial, endothelial, and mixed.

PKP

Epithelial rejection occurs in roughly 2% of graft rejections. [6] It begins as a line located near engorged limbal vessels, with migration across the graft-recipient interface. The line consists of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils. These lines can precede endothelial rejection by days to weeks.

Subepithelial rejections are the least common type of rejection with an occurrence rate of 1% [6]. They are deeper infiltrates caused by rejection of stromal keratocytes. Subepithelial rejection can proceed to endothelial rejection.[9] They are randomly distributed in the central cornea and can occur along an epithelial rejection line or alone. They may also precede endothelial graft rejection, as early as 6 weeks or as late as 2 years after transplantation. However, corneal allograft does not typically occur in the first month.[9]

The most common form of graft rejection is endothelial rejection, occurring in 50% of rejection episodes. [6] However, if graft rejection is diagnosed early and treated with corticosteroids aggressively, irreversible graft failure can often be avoided by minimizing the loss of endothelial cells. Endothelial rejection consists of a line of KPs beginning inferiorly at the graft-host junction and marching superiorly. The limbus may be hyperemic, with an anterior chamber reaction but cells may not be visible due to a diffusely edematous cornea.

Finally, a mixed rejection occurs in 30% of episodes [6].

DALK

Stromal immune rejection can occur in DALK between 1-24%. [10] Clinically, stromal rejection can present with stromal infiltrates, neovascularization within the graft- host interface.[9]

DSEK

DSEK has a mean endothelial rejection rate of 10% (range 0% to 45%) and an average primary graft failure of 5% (range 0% to 29%) according to a review by the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO).[11] See Early endothelial rejection.[12]

DMEK

DMEK has a very low rejection rate (mean of 1.9%, range 0% to 5.9%).[13] According to a 2017 report by the AAO, DMEK has a primary graft failure rate of 1.7% (range 0% to 12.5%) and a secondary graft failure rate of 2.2% (range 0% to 6.3%).[13]

Management

Transplant rejection is one of the most difficult complications to manage after keratoplasty. The management and likelihood of reversibility is largely determined by the corneal layer affected. It is important to avoid transplanting an eye that is actively inflamed if possible. Corneal grafts performed while the eye has active inflammation are more likely to reject.[14]

Topical steroids are the primary treatment for acute graft rejection and as post operative prophylactic therapy for high- risk transplant recipients. For epithelial and subepithelial rejections, which have a higher rate of reversibility, topical corticosteroids can be used six times per day, with a tapered dosing over 6-8 weeks. [15] In contrast, severe endothelial rejection requires topical corticosteroids prescribed hourly (prednisolone acetate 1% q1h or difluprednate 0.05% q2h) in combination with systemic therapy; either 40 to 80mg of oral prednisone daily or a single-pulse or three-pulse intravenous dose of 500mg of methylprednisolone with or without subconjunctival betamethasone 3mg in 0.5mL. [16] Topical tacrolimus can also be considered.[9]

Given the high side effect profile of prolonged corticosteroid use including, cataract formation, glaucoma, impaired wound healing, and immunosuppression, alternative therapeutics are being investigated.

Calcineurin inhibitors, including cyclosporine (CsA) and tacrolimus (FK-506), are viable options for patients in whom corticosteroids are contraindicated. Although the efficacy of cyclosporine A 0.5% is mixed; it may be substituted for topical corticosteroids to aid in the management of steroid response and post-keratoplasty glaucoma . [17] However, there was a rejection rate of 12% (6 out of 52 eyes) of patients while on topical cyclosporine alone, five of which were reversed with the reintroduction of topical corticosteroids. [17] Tacrolimus can be used topically or systemically. One study demonstrated that topical 0.03% tacrolimus was effective in preventing irreversible rejection in patients with high-risk corneal transplantation without increasing IOP.[18] Systemic administration of oral tacrolimus (2–12mg daily) is also beneficial in preventing and treating graft rejection in high-risk patients, with a clear graft survival rate of 65%. [19]

Novel therapeutics:

Corneal neovascularization is a strong determinant of graft survival and poses a challenge to reinstating ocular immune privilege after surgery. Fasciani et al demonstrated promising results of using anti-VEGF agents as a preconditioning treatment in patients affected by high immune risk and corneal neovascularization. [20] Compared to controls that directly underwent penetrating keratoplasty, patients who underwent three subconjunctival intrastromal injections of 5mg in 0.2ml bevacizumab experienced no episodes of corneal graft rejection at a mean follow up of 26 months. In contrast, six of thirteen eyes (46%) in the control group showed evidence of graft rejection at a mean follow- up of 3.8 months.[20]

Additional Resources

- Boyd K, McKinney JK. Eye Donation. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/treatments/eye-donation-list. Accessed March 11, 2019.

References

- ↑ Hjortdal J, Pedersen IB, Bak-nielsen S, Ivarsen A. Graft rejection and graft failure after penetrating keratoplasty or posterior lamellar keratoplasty for fuchs endothelial dystrophy. Cornea. 2013;32(5):e60-3.

- ↑ Dana MR, Qian Y, Hamrah P. Twenty-five-year panorama of corneal immunology: emerging concepts in the immunopathogenesis of microbial keratitis, peripheral ulcerative keratitis, and corneal transplant rejection. Cornea. 2000;19(5):625-43.

- ↑ Bartels MC, Doxiadis II, Colen TP, Beekhuis WH. Long-term outcome in high-risk corneal transplantation and the influence of HLA-A and HLA-B matching. Cornea. 2003;22(6):552-6.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Krachmer J, Mannis M, Holland E: CORNEA, 2nd ed.Elsevier Mosby, 2005, 1284-1314.

- ↑ Wilhelmus KR, Stulting RD, Sugar J, Khan MM. Primary corneal graft failure. A national reporting system. Medical Advisory Board of the Eye Bank Association of America. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:1497-502.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Guilbert E, Bullet J, Sandali O, Basli E, Laroche L, Borderie VM. Long-term rejection incidence and reversibility after penetrating and lamellar keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155(3):560-569.e2.

- ↑ Price MO, Jordan CS, Moore G, Price FW, Jr. Graft rejection episodes after Descemet stripping with endothelial keratoplasty: part two: the statistical analysis of probability and risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93:391-5.

- ↑ Abu Dail Y, Daas L, Flockerzi E, et al. PCR testing for herpesviruses in aqueous humor samples from patients with and without clinical corneal endothelial graft rejection. J Med Virol. Mar 2024;96(3):e29538. doi:10.1002/jmv.29538

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Basic and Clinical Science Course External Disease and Cornea vol 8. 1. American Academy of Ophthalmology 2022- 2023.

- ↑ Reinhart WJ, Musch DC, Jacobs DS, Lee WB, Kaufman SC, Shtein RM. Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty as an alternative to penetrating keratoplasty a report by the american academy of ophthalmology. O hthalmology 2011;118:209-18.

- ↑ Lee WB, Jacobs DS, Musch DC, Kaufman SC, Reinhart WJ, Shtein RM. Descemet's stripping endothelial keratoplasty: safety and outcomes: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2009;116:1818-30.

- ↑ Corneal Graft Survival and COVID Vaccines. EyeNet Magazine. American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/corneal-graft-survival-and-covid-vaccines Accessed February 8, 2024.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Deng SX, Lee WB, Hammersmith KM, et al. Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty: Safety and Outcomes: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2018;125:295-310.

- ↑ Williams KA, Roder D, Esterman A, Muehlberg SM, Coster DJ. Factors Predictive of Corneal Graft Survival. Ophthalmology 1992;99:403-14.

- ↑ Qazi Y, Hamrah P. Corneal Allograft Rejection: Immunopathogenesis to Therapeutics. J Clin Cell Immunol. 2013;2013(Suppl 9).

- ↑ Gerstenblith AT, Rabinowitz MP. The Wills Eye Manual, Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Perry HD, Donnenfeld ED, Acheampong A, Kanellopoulos AJ, Sforza PD, et al. Topical Cyclosporine A in the management of postkeratoplasty glaucoma and corticosteroid-induced ocular hypertension (CIOH) and the penetration of topical 0.5% cyclosporine A into the cornea and anterior chamber. CLAO J. 1998; 24:159–165.

- ↑ Magalhaes OA, Marinho DR, Kwitko S. Topical 0.03% tacrolimus preventing rejection in high-risk corneal transplantation: a cohort study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(11):1395-1398.

- ↑ Joseph A, Raj D, Shanmuganathan V, Powell RJ, Dua HS. Tacrolimus immunosuppression in high-risk corneal grafts. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007; 91:51–55.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 Fasciani R, Mosca L, Giannico MI, Ambrogio SA, Balestrazzi E. Subconjunctival and/or intrastromal bevacizumab injections as preconditioning therapy to promote corneal graft survival. Int Ophthalmol. 2014.