Conjunctival Papilloma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

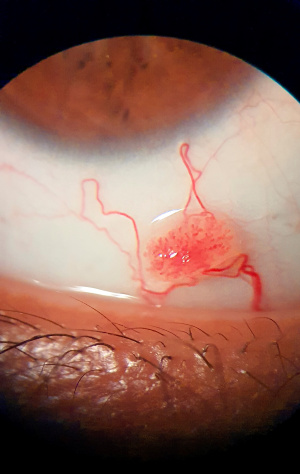

In general, papilloma is a histopathological term describing tumors with specific morphology. They take on a classic finger like or cauliflower like appearance. Papillomatous lesions often are lobulated with a central vascular core.

Irrelevant of its cytology, a neoplasm of epithelial origin with this form of growth is also called papilloma. Papillomas can be benign or malignant and can be found in numerous anatomical locations (eg, skin, conjunctiva, cervix, breast duct). Specifically, conjunctival papillomas are benign squamous epithelial tumors with minimal propensity toward malignancy.

Conjunctival papillomas are categorized into infectious (viral), squamous cell, limbal, and inverted (histological description) based on appearance, location, patient's age, propensity to recur after excision, and histopathology. They demonstrate an exophytic growth pattern. Interestingly, inverted papillomas exhibit exophytic and endophytic growth patterns.

Conjunctival papilloma also can be classified based on gross clinical appearance, as either pedunculated or sessile. The pedunculated type is synonymous with infectious conjunctival papilloma and squamous cell papilloma. The limbal conjunctival papilloma often is referred to as noninfectious conjunctival papilloma because it is believed that limbal papillomas arise from UV radiation exposure. Because of its gross appearance, limbal papillomas are typed as sessile. Although rare, inverted conjunctival papillomas sometimes are referred to as mucoepidermoid papillomas because these lesions possess both a mucous component and an epidermoid component.

A strong association exists between Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) types 6 and 11 and the development of conjunctival papillomas. Infectious conjunctival papillomas also are known as squamous cell papillomas. This term arises from its histopathological appearance (i.e., the lesion is confined to the epithelial layer, which is acanthotic).

Disease Entity

Epidemiology

Frequency - United States

Literature reviewed yielded no published study outlining the prevalence of conjunctival papillomas in a cross section of a population. Interestingly, studies are numerous for extraocular sites. Prevalence of conjunctival papillomas ranged from 4-12%. A strong association exists between HPV and squamous cell papilloma. Moreover, the HPV genome is identifiable in most conjunctival papillomas and in 85% of conjunctival dysplasias and carcinomas.

Although no cross-section epidemiological studies are available, evidence suggests that people without overt clinical presentation may harbor the virus, and HPV DNA can be identified in asymptomatic conjunctiva. HPV types 6 and 11 are the most frequently found in conjunctival papilloma. HPV type 33 is another source in the pathogenesis of conjunctival papilloma. HPV types 16 and 18 commonly are associated with not only high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive carcinoma but also squamous cell dysplasia and carcinoma of the conjunctiva. The recurrence rate for infectious papillomas is high. Limbal papillomas have a recurrent rate of 40%.

Mortality/Morbidity

Conjunctival papillomas (squamous cell, limbal, or inverted) are not life threatening. Conjunctival papillomas may be large enough to be displeasing or cosmetically disfiguring. HPV types 6 and 11 may be transferred to the child during parturition from an infected birth canal resulting in ocular symptoms.

Egbert et al reported a case of conjunctival papilloma in an infant born to a mother with HPV infection of the vulva during pregnancy.[1] Those infected at birth may later develop respiratory papillomatosis, which may be life threatening. Direct contact with contaminated hands or objects may result in ocular manifestations.

Squamous cell papilloma, which has an infectious viral etiology, has the propensity to recur after medical and surgical treatment. New and multiple lesions may arise after excision. Recurrent conjunctival papillomas may extend into the nasolacrimal duct causing obstruction. Lauer et al and Migliori and Putterman reported a case of nasolacrimal duct obstruction after extension of the papillomas into the lacrimal sac.[2] [3] Most papillomas are benign. Rarely, they can undergo malignant transformation, signs of which include inflammation, keratinization, and symblepharon formation.

Age

Squamous cell papillomas (ie, infective papilloma, viral conjunctival papilloma) are seen commonly in children and young adults, usually younger than 20 years. Because HPV is associated strongly with this form of papilloma, siblings, including twins, also may be affected. Limbal papillomas are seen commonly in older adults. A slight association exists between UV radiation and limbal conjunctival papilloma.

General Pathology

Histological Findings

Squamous cell papillomas (eg, infectious papilloma, viral conjunctival papilloma) are composed of multiple branching fronds emanating from a narrow pedunculated base. Individual fronds are surrounded by connective tissue, each having a central vascularized core. Acute and chronic inflammatory cells are found within these fronds. The epithelium is acanthotic, nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium without atypia. Numerous goblet cells are seen along with acute inflammatory cells. Koilocytosis is exhibited. The basement membrane is intact.

Limbal papillomas are sessile lesions arising from a broad base with a gelatinous appearance. Corkscrew vascular loops and feeder vessels are seen. The epithelium is acanthotic, displaying varying degrees of pleomorphism and dysplasia. The epithelium surface may be keratinized with foci of parakeratosis within the papillary folds. The basement membrane is intact.

Inverted papillomas exhibit exophytic and endophytic growth patterns. Invagination into the underlying stroma instead of the exophytic growth pattern is exhibited by squamous cell or limbal papillomas, whereas some lesions exhibit a mixture of exophytic and endophytic growth patterns. Unlike inverted papilloma arising in the lateral nasal wall or paranasal sinuses, lesions arising from the conjunctiva tend to be less aggressive in malignant transformation. The lesions are composed of lobules of epithelial cells extending down into the stroma. The lesion may be elevated or umbilicated. Epithelial cells do not demonstrate atypia, and dysplastic changes are uncommon for conjunctival inverted papillomas. The cytoplasm is vacuolated in some cells. They may resemble squamous papilloma or pyogenic granuloma. Numerous goblet cells are intermixed with the epithelium. Cystic lesions may be seen secondary to the confluence of goblet cells. The lesion may contain melanin granules and/or melanocytes.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology's Pathology Atlas contains a virtual microscopy image of Papilloma Conjunctiva.

Pathophysiology

Human papillomavirus (HPV) and polyomavirus are members of the Papovavirus family. These viruses are small (55 nm), naked, and icosahedral with circular double-stranded DNA. Papilloma viruses exhibit site and cell-type specificity, as follows:

- HPV 6 and 11 – Benign skin warts or condylomas of the female genital tract and conjunctival papilloma

- HPV 16 and 18 – Cervical carcinoma

- HPV 6a and 45, two new subtypes, have been reported to be associated with conjunctival papilloma.[4] [5]

Transmission is via direct human contact. Proliferation of dermal connective tissue is followed by acanthosis and hyperkeratosis. HPV is tumorigenic, and it commonly produces benign tumors with low potential for malignancy. In general, prolonged proliferation may lead to cellular atypia and dysplasia. HPV type 11 was the most common and frequently found in conjunctival papilloma as analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).[6]

History

General approach

- A good ocular history is not only essential but also critical in making the correct diagnosis.

- Knowing the patient's age and the anatomical location of the tumor or tumor like lesion (eg, inverted papillomas [Schneiderian or mucoepidermoid papillomas] typically involve the mucous membrane of the nose, paranasal sinuses, and lacrimal sac) is helpful for the ophthalmologist. The conjunctiva is rarely affected.

- A change in size and shape should raise the index of suspicion for a possible neoplastic proliferation. However, other reasons may contribute to the change in size. Cystic lesions may increase in size secondary to accumulation of fluids and/or acellular debris. An inflammatory response may cause a benign lesion to increase in size.

- Most conjunctival tumors are isolated lesions. However, in a small percentage, conjunctival lesions may be an extension of systemic disease (ie, Lhermitte-Duclos disease, Cowden syndrome).

- A history of congenital, bilateral, or multifocal conjunctival lesions strongly suggests an underlying systemic disease. Therefore, a profound systemic workup is warranted.

History associated with conjunctival papilloma

Squamous cell papilloma

- Usually seen in younger patients

- History of maternal HPV infection at the time of parturition

- A past history of tumor excision with recurrence

- Refractive to past medical and surgical treatments

- No decrease or loss of visual acuity

- A history of a sibling with the same condition

- A history of cutaneous warts at extraocular sites

Limbal papilloma

- Seen in older adults

- History of UV exposure

- Possible decrease or loss of visual acuity

- Recurrence after excision, not common

- History of chronic conjunctivitis refractive to medications

Physical examination

Key features to assist an ophthalmologist in examining a surface tumor include the following:

Tumor location: Knowing the probability of finding a tumor in a specific anatomical location greatly assists the ophthalmologist not only in making the diagnosis but also, and more importantly, in prioritizing the differential diagnosis.

- Approximately 25% of all lesions involving the caruncle are papillomas.

- Squamous cell carcinoma is seen commonly in the interpalpebral zone adjacent to the limbus and rarely appears elsewhere. Although possible, a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma would be questionable if remote from the limbus.

Tumor color: Tumor color provides important clues and clinical judgment based on the following:

- Pigmented lesions suggest a melanocytic origin.

- Salmon-colored lesions are associated with lymphoid tumors.

- Pale or dull yellow lesions are associated with xanthomas.

Tumor topography: In evaluating, attention should be made to the tumor's surface, to include the tumor's texture and edge.

- The conjunctiva surface appearance is altered predictably in epithelial tumors (ie, the surface epithelium is raised, cobblestone, and/or acanthotic).

- In differentiating from epithelial tumors, tumors arising from the substantia propria tend to have a smooth epithelial surface.

- Tumor edges between normal conjunctiva and diseased conjunctiva may appear abrupt, as seen in conjunctival papilloma or conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

- In cases where the edges are ill defined, lymphoid tumors should be considered.

Tumor growth pattern: The pattern of growth may be described as solitary, diffuse, or multifocal.

- Solitary growth is seen in conjunctival papilloma.

- Diffuse growth, although rare, is associated with conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia, sebaceous carcinoma (pagetoid spread), lymphoma, and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia.

Tumor consistency: The tumor consistency can be described as solid, soft, or cystic.

- Tumor consistency is established by palpation, which is useful in evaluating and diagnosing subepithelial tumors.

- Palpation is performed under topical anesthesia during the slit lamp examination, using a cotton-tip applicator.

- This technique is beneficial in determining whether an epithelial tumor has invaded the underlying supporting tissue. Most papillomas are freely mobile over the sclera. An epithelial tumor that has already invaded the underlying connective tissue will feel fastened to the globe when tenderly pushed from side to side.

Signs

Clinical signs associated with squamous cell papilloma (infectious papilloma) are as follows:

- This lesion is benign and self-limiting.

- It is seen commonly in children and young adults.

- Most lesions are asymptomatic without associated conjunctivitis or folliculitis.

- Anatomically, it commonly is located in the inferior fornix, but it also may arise in the limbus, caruncle, and palpebral regions.

- The lesion may be bilateral and multiple.

- Grossly, squamous cell papilloma appears as a grayish red, fleshy, soft, pedunculated mass with an irregular surface (cauliflowerlike).

Clinical signs associated with limbal papilloma are as follows:

- This lesion is typically benign.

- It is seen commonly in older adults.

- Anatomically, the lesion commonly occurs at the limbus or the bulbar conjunctiva.

- These lesions may spread centrally toward the cornea or laterally toward the conjunctiva.

- Visual acuity may be affected if the lesion grows centrally.

- These lesions almost always are unilateral and single.

- They tend to have variable proliferation potential with a tendency to slowly enlarge in size.

Clinical signs associated with inverted conjunctival papilloma are as follows:

- This lesion is slow growing and is seen commonly in the nose, paranasal sinuses, or both. The lacrimal sac and the conjunctiva are uncommon sites.

- The lesion is unilateral and unifocal and does not recur after surgical excision.

Differential diagnosis

- Ichthyosis

- Sebaceous Gland Carcinoma

- Conjunctival Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Management

Observation and patient reassurance are indicated for squamous cell papillomas. These lesions may regress spontaneously over time. Seeding may follow excision, resulting in multiple new lesions. For limbal papillomas, excision is indicated to rule out neoplastic changes.

Cryotherapy is indicated for squamous cell papillomas. Less scarring occurs, and the recurrence rate is low. It is not indicated for limbal papillomas because this procedure does not distinguish between benign papillomas and malignant papillomas. The double-freeze-thaw method is preferred and appears to be the most effective technique.

Dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB): Petrelli et al demonstrated success with DNCB in the treatment of recurrent conjunctival papillomas.[7] This treatment modality is reserved for cases when surgical excision, cryoablation, and other treatment modalities have failed. The patient is sensitized to DNCB. Once sensitized, DNCB is applied directly to the papilloma. The mechanism for this treatment appears to be the delayed hypersensitivity reaction causing the tumor to regress; however, the exact mechanism is unknown.

Interferon is an adjunct therapy to surgical excision of recurrent and multiple lesions. Alpha interferon is given intramuscularly (daily for 1 mo, 2-3 times/wk for the next 6 mo, then tapered off). Lass et al indicated both nonrecurrence and recurrence of conjunctival lesions.[8] However, those recurring lesions tend to be less severe in clinical presentation. Because of its antiviral and antiproliferative properties, this form of therapy is designed to suppress tumor cells; it is not curative. Additionally, topical interferon alpha-2b has been shown to be an effective adjunct therapy for small-to-medium size lesions but not for large lesions without surgical debulking. Topical interferon alpha-2b can be utilized as an adjunctive therapy for recurring conjunctival papilloma.[9] [10] More recently, topical alpha-2b interferons have shown to be successful in treating not only primary conjunctival papilloma but also conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia.[11]

Mitomycin-C is an adjunct therapy to surgical excision. Mitomycin-C is indicated for recalcitrant conjunctival papillomas or those refractive to past multiple treatments. Hawkins et al reported complete regression of conjunctival papilloma 9 months after surgical excision followed by intraoperative mitomycin-C application.[12] Mitomycin-C (0.3 mg/mL) is applied via a cellulose sponge to the involved area(s) after surgical excision. The sponge is held in place for 3 minutes. The treated area is irrigated copiously with normal saline after mitomycin-C application. Complications include symblepharon, corneal edema, corneal perforation, iritis, cataract, and glaucoma.

Oral cimetidine (Tagamet): Although commonly used to treat peptic ulcer disease, cimetidine has shown to be effective in the treatment of recalcitrant conjunctival papilloma. Shields et al demonstrated dramatic tumor regression with nearly complete resolution in an 11-year-old boy treated with cimetidine.[13] Chang et al indicated that oral cimetidine can be used as an initial treatment modality in cases where the lesion is quite large and recalcitrant.[14] Apart from its antagonistic effect on H2 receptors, cimetidine has been found to enhance the immune system by inhibiting suppressor T-cell function and augmenting delayed-type hypersensitivity responses.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) laser: Schachat et al and Jackson et al reported this treatment modality to be safe and most effective.[15] [16] It is indicated for recalcitrant conjunctival papillomas. The procedure is performed easily. This procedure allows for precise tissue excision with minimal blood loss and trauma to tissue. Rapid healing of tissues occurs without significant scarring, edema, or symblepharon formation. Recurrence is low, resulting from the destruction of viral particles and papillomatous epithelial cells. Gentamicin ointment twice a day for 7-10 days is prescribed postoperatively to allow proper healing and reepithelialization.

Other treatment modalities include electrodesiccation, topical acids, topical cantharidin, and intralesional bleomycin.

Excision is indicated for squamous cell and limbal papillomas.

- Performing an excisional biopsy is recommended for adults to rule out premalignancy changes.

- In the pediatric population, performing an excisional biopsy is less clear. This is a surgical procedure requiring general anesthesia. To justify the risk of anesthesia, this procedure is indicated in cases where the lesion is causing significant symptoms, (ie, cosmetically disfiguring, has not regressed, appearance of new lesion).

An excisional biopsy is preferred to an incisional biopsy whenever possible.

Medical therapy

The goals of pharmacotherapy are to reduce morbidity and to prevent complications.

- H2-receptor antagonists (Cimetidine)

- Immune Modulators (Dinitrochlorobenzene)

- Interferon (Interferon alpha-2b)

- Antineoplastic agents (mytomycin-C)

Surgery

Biopsy (incisional or excisional) is a reasonable and safe method that aids in obtaining a definitive diagnosis.

Indications for a biopsy are as follows:

- To rule in or to rule out the possibility of malignancy

- For lesions not obviously benign (symptomatic and/or show growth)

- For neoplasms suggestive of malignancy (HIV-positive patients or chronic unilateral conjunctivitis unresponsive to therapy)

- Therapeutic decision

- To determine the surgical margin in ill-defined lesions

- To exclude the possibility of recurrent neoplastic changes

- To harvest tissue for special studies (ie, flow cytometry)

Frozen section

- The most common indication for a frozen section is to determine whether surgical margins are free of tumor (ie, to assess the adequacy of tissue excision).

- A frozen section should not be used for an "on-the-spot" diagnosis, since frozen tissue rendered tissue morphology is less optimal for microscopic examination.

- Invasive disease can be excluded, but intraepithelial lesions may not.

- Conjunctival tissue tends to curl after excision; therefore, it is best to examine after fixation and inking the borders. After obtaining the biopsy, place the tissue flat on a piece of firm paper/cardboard before placing in fixation medium.

Surface tissue sampling

Exfoliative cytology (tissue scraping)

- This technique is used commonly to aid in the diagnosis of cervical disease. However, this technique and its role in aiding the ophthalmologist in diagnosing ocular surface lesions are less well defined.

- Major limitations include the possibility of false-negative results and its inability to determine the depth of invasion.

- Most benign and inflammatory lesions cannot be identified precisely by cytologic methods.

- It is useful as a guide for where to obtain a biopsy specimen or resect ill-defined conjunctival lesions.

Impression cytology

- Another technique for collecting surface cells, impression cytology uses a cellulose acetate filter paper. When the filter paper is placed in direct contact with the surface cells, the cells adhere to the paper.

- Impression cytology is less traumatic than exfoliative cytology.

- Intracellular structures are better preserved than with exfoliative cytology.

- Limitations are similar to exfoliative cytology; both are not appropriate for identifying intraepithelial tumors.

Surgical follow up

For patients who undergo cryoablation, CO2 laser, or surgical excision for conjunctival papilloma, posttreatment follow-up care is usually at 5 days, at 1 month, and then at 1 year.

Patients on a medical regimen should receive monthly follow-up care for possible adverse effects until the medication is discontinued. Later, these patients should receive annual follow-up care to check for recurrence of the lesion.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with this condition is generally good.

- Recurrences of viral papillomas are not uncommon.

- Recurrences of completely excised squamous cell papillomas are uncommon.

Patients should receive routine follow-up care for recurrences.

- Inform patients that the lesion may recur after excision and that multiple recurrences are not uncommon.

- Recurrence of lesions may require more aggressive treatment.

- Theoretically, decreasing sun exposure may prevent squamous cell lesions.

References

- ↑ Egbert JE, Kersten RC. Female genital tract papillomavirus in conjunctival papillomas of infancy. Am J Ophthalmol. Apr 1997;123(4):551-2.

- ↑ Lauer SA. Recurrent conjunctival papilloma causing nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. Nov 15 1990;110(5):580-1.

- ↑ Migliori ME, Putterman AM. Recurrent conjunctival papilloma causing nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. Jul 15 1990;110(1):17-22.

- ↑ Peck N, Lucarelli MJ, Yao M, et al. Human papillomavirus 6a lesions of the lower eyelid and genitalia. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. Jul-Aug 2006;22(4):311-3.

- ↑ Sjo NC, Buchwald CV, Cassonnet P, et al. Human papillomavirus in normal conjunctival tissue and in conjunctival papilloma. Types and frequencies in a large series. Br J Ophthalmol. Dec 13 2006.

- ↑ Minchiotti S, Masucci L, Serapiao Dos Santos M, Perrella E, Graffeo R, Lambiase A. Conjunctival papilloma and human papillomavirus: identification of HPV types by PCR. Eur J Ophthalmol. May-Jun 2006;16(3):473-7.

- ↑ Petrelli R, Cotlier E, Robins S, Stoessel K. Dinitrochlorobenzene immunotherapy of recurrent squamous papilloma of the conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. Dec 1981;88(12):1221-5.

- ↑ Lass JH, Foster CS, Grove AS, et al. Interferon-alpha therapy of recurrent conjunctival papillomas. Am J Ophthalmol. Mar 15 1987;103(3 Pt 1):294-301.

- ↑ Muralidhar R, Sudan R, Bajaj MS, Sharma V. Topical interferon alpha-2b as an adjunctive therapy in recurrent conjunctival papilloma. Int Ophthalmol. Feb 2009;29(1):61-2.

- ↑ de Keizer RJ, de Wolff-Rouendaal D. Topical alpha-interferon in recurrent conjunctival papilloma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. Apr 2003;81(2):193-6.

- ↑ Falco LA, Gruosso PJ, Skolnick K, Bejar L. Topical interferon alpha 2 beta therapy in the management of conjunctival papilloma. Optometry. Apr 2007;78(4):162-6.

- ↑ Hawkins AS, Yu J, Hamming NA, Rubenstein JB. Treatment of recurrent conjunctival papillomatosis with mitomycin C. Am J Ophthalmol. Nov 1999;128(5):638-40.

- ↑ Shields CL, Lally MR, Singh AD, et al. Oral cimetidine (Tagamet) for recalcitrant, diffuse conjunctival papillomatosis. Am J Ophthalmol. Sep 1999;128(3):362-4.

- ↑ Chang SW, Huang ZL. Oral cimetidine adjuvant therapy for recalcitrant, diffuse conjunctival papillomatosis. Cornea. Jul 2006;25(6):687-90.

- ↑ Schachat A, Iliff WJ, Kashima HK. Carbon dioxide laser therapy of recurrent squamous papilloma of the conjunctiva. Ophthalmic Surg. Nov 1982;13(11):916-8.

- ↑ Jackson WB, Beraja R, Codere F. Laser therapy of conjunctival papillomas. Can J Ophthalmol. Feb 1987;22(1):45-7.

- Bailey RN, Guethlein ME. Diagnosis and management of conjunctival papillomas. J Am Optom Assoc. May 1990;61(5):405-12.

- Bosniak SL, Novick NL, Sachs ME. Treatment of recurrent squamous papillomata of the conjunctiva by carbon dioxide laser vaporization. Ophthalmology. Aug 1986;93(8):1078-82.

- Buggage RR, Smith JA, Shen D, Chan CC. Conjunctival papillomas caused by human papillomavirus type 33. Arch Ophthalmol. Feb 2002;120(2):202-4.

- Campbell RJ. Tumors of the eyelids, conjunctiva, and cornea. In: Garner A, Klintworth GK, eds. Pathobiology of Ocular Disease - A Dynamic Approach. Marcel Dekker Inc; 1994:1367-8(chap 46).

- Chang T, Chapman B, Heathcote JG. Inverted mucoepidermoid papilloma of the conjunctiva. Can J Ophthalmol. Jun 1993;28(4):184-6.

- Chiemchaisri Y, Dongosintr N, Wasi C, et al. The regression of recurrent conjunctival papillomas by lymphoblastoid interferon treatment. J Med Assoc Thai. Jul 1990;73(7):406-13.

- Eagle RC. Conjunctiva. In: Eye Pathology - An Atlas and Basic Text. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1999:47-8, 59, 61-2(chap 4).

- Easty DL, Williams C. Viral and rickettsial disease. In: Garner A, Klintworth GK, eds. Pathobiology of Ocular Disease - A Dynamic Approach. Marcel Dekker Inc; 1994:247(chap 7).

- Harkey ME, Metz HS. Cryotherapy of conjunctival papillomata. Am J Ophthalmol. Nov 1968;66(5):872-4.

- Hsu HC, Lin HF. Eyelid tumors in children: a clinicopathologic study of a 10-year review in southern Taiwan. Ophthalmologica. Jul-Aug 2004;218(4):274-7.

- Jakobiec FA, Harrison W, Aronian D. Inverted mucoepidermoid papillomas of the epibulbar conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. Mar 1987;94(3):283-7.

- Khalil MK, Pierson RB, Mihalovits H, et al. Intraepithelial neoplasia of the bulbar conjunctiva clinically presenting as diffuse papillomatosis. Can J Ophthalmol. Oct 1993;28(6):287-90.

- Kremer I, Sandbank J, Weinberger D, et al. Pigmented epithelial tumours of the conjunctiva. Br J Ophthalmol. May 1992;76(5):294-6.

- Lass JH, Grove AS, Papale JJ, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA sequences in conjunctival papilloma. Am J Ophthalmol. Nov 1983;96(5):670-4.

- Lass JH, Jenson AB, Papale JJ, Albert DM. Papillomavirus in human conjunctival papillomas. Am J Ophthalmol. Mar 1983;95(3):364-8.

- Mantyjarvi M, Syrjanen S, Kaipiainen S, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus type 11 DNA in a conjunctival squamous cell papilloma by in situ hybridization with biotinylated probes. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). Aug 1989;67(4):425-9.

- Margo CE, Mack WP. Therapeutic decisions involving disparate clinical outcomes: patient preference survey for treatment of central retinal artery occlusion. Ophthalmology. Apr 1996;103(4):691-6.

- McDonnell JM, Lass JH. Human papillomavirus diseases. In: Pepose JS, et al, eds. Ocular Infection and Immunity. New York: Mosby; 1996:857-68(chap 67).

- McDonnell JM, McDonnell PJ, Mounts P, et al. Demonstration of papillomavirus capsid antigen in human conjunctival neoplasia. Arch Ophthalmol. Dec 1986;104(12):1801-5.

- McDonnell PJ, McDonnell JM, Kessis T, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus type 6/11 DNA in conjunctival papillomas by in situ hybridization with radioactive probes. Hum Pathol. Nov 1987;18(11):1115-9.

- McLean IW, et al. Tumors of the conjunctiva (Chapter 3). In: Tumors of the Eye and Ocular Adnexa. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology;1994:49-52.

- Mincione GP, Taddei GL, Wolovsky M, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA type 6/11 in a conjunctival papilloma by in situ hybridization with biotinylated probes. Pathologica. Jul-Aug 1992;84(1092):483-8.

- Miyagawa M, Hayasaka S, Nagaoka S, Mihara M. Sebaceous gland carcinoma of the eyelid presenting as a conjunctival papilloma. Ophthalmologica. 1994;208(1):46-8.

- Morsman CD. Spontaneous regression of a conjunctival intraepithelial neoplastic tumor. Arch Ophthalmol. Oct 1989;107(10):1490-1.

- Omohundro JM, Elliott JH. Cryotherapy of conjunctival papilloma. Arch Ophthalmol. Nov 1970;84(5):609-10.

- Pfister H, Fuchs PG, Volcker HE. Human papillomavirus DNA in conjunctival papilloma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1985;223(3):164-7.

- Rumelt S, Pe'er J, Rubin PA. The clinicopathological spectrum of benign peripunctal tumours. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. Feb 2005;243(2):113-9.

- Saegusa M, Takano Y, Hashimura M, et al. HPV type 16 in conjunctival and junctional papilloma, dysplasia, and squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. Dec 1995;48(12):1106-10.

- Schechter BA, Rand WJ, Velazquez GE, et al. Treatment of conjunctival papillomata with topical interferon Alfa-2b. Am J Ophthalmol. Aug 2002;134(2):268-70..

- Slade CS, Katz NN, Whitmore PV, Bardenstein DS. Conjunctival and canalicular papillomas and ichthyosis vulgaris. Ann Ophthalmol. Jul 1988;20(7):251-5.

- Spencer WH. Neoplasms and related conditions (Chapter 2). In: Ophthalmic Pathology - An Atlas and Textbook. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co;1996:106-11.

- Wells GB, Lasner TM, Yousem DM, Zager EL. Lhermitte-Duclos disease and Cowden's syndrome in an adolescent patient. Case report. J Neurosurg. Jul 1994;81(1):133-6.

- Wilson FM, Ostler HB. Conjunctival papillomas in siblings. Am J Ophthalmol. Jan 1974;77(1):103-7.

- Yanoff M, Fine BS. Conjunctiva - pseudocancerous lesions. In: Ocular Pathology. 4th ed. New York: Mosby-Wolfe; 1996:220-1(chap 7).

- Ocular Pathology Atlas. American Academy of Ophthalmology Web site. https://www.aao.org/resident-course/pathology-atlas. Published 2016. Accessed January 4, 2017.