Comprehensive Suture Guide

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Choosing Suture

One key to successful ophthalmologic surgery is a solid understanding of different suture types and choosing which is best suited to achieve the desired effect. Thus, it is imperative to differentiate between the variety of sutures available to the surgeon, and know how individual characteristics of the needle and thread influence the suture performance.

To the beginning ophthalmologist, the plethora and variety of surgical sutures can be overwhelming. This guide will help break down the thought process behind choosing suture and outline the benefits and drawbacks of each type. As always, availability at your specific location will ultimately dictate what tools you have at your disposal.

Suture Anatomy

In its simplest form suture is basically a needle attached to a thread, in surgery these are sterile and come in a large variety of shapes and sizes. This article aims to present the suture options available in most surgical centers and their common applications in ophthalmic surgery.

The suture needle can be from around 5.5mm to 13 mm, shaped as pointed, spatulated, reverse cutting, tapercut, straight cutting, conventional cutting, and others. It can be straight or curved, and there can be single, or double armed sutures.

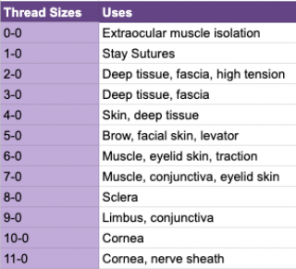

The suture thread can range from around 15-45 inches, be permanent or dissolvable, braided or monofilament, and made from silk, polypropylene, nylon, polyglactin, chromic/gut, gore-tex, polyester, or other materials. There can be two needles attached to the suture (double armed) or it can have a single needle on one end (single armed). The thickness of the thread shaft decreases as the assigned number increases, with the thickest being 0-0 and thinnest 11-0. The second "-0" is by convention and has little practical significance.

The following information is meant to delineate available suture types, their functions, and common uses. As with any surgical technique, there are multiple approaches that will lead to success. These data can be used as a foundation for discovering what works best in each surgeon’s specific situation.

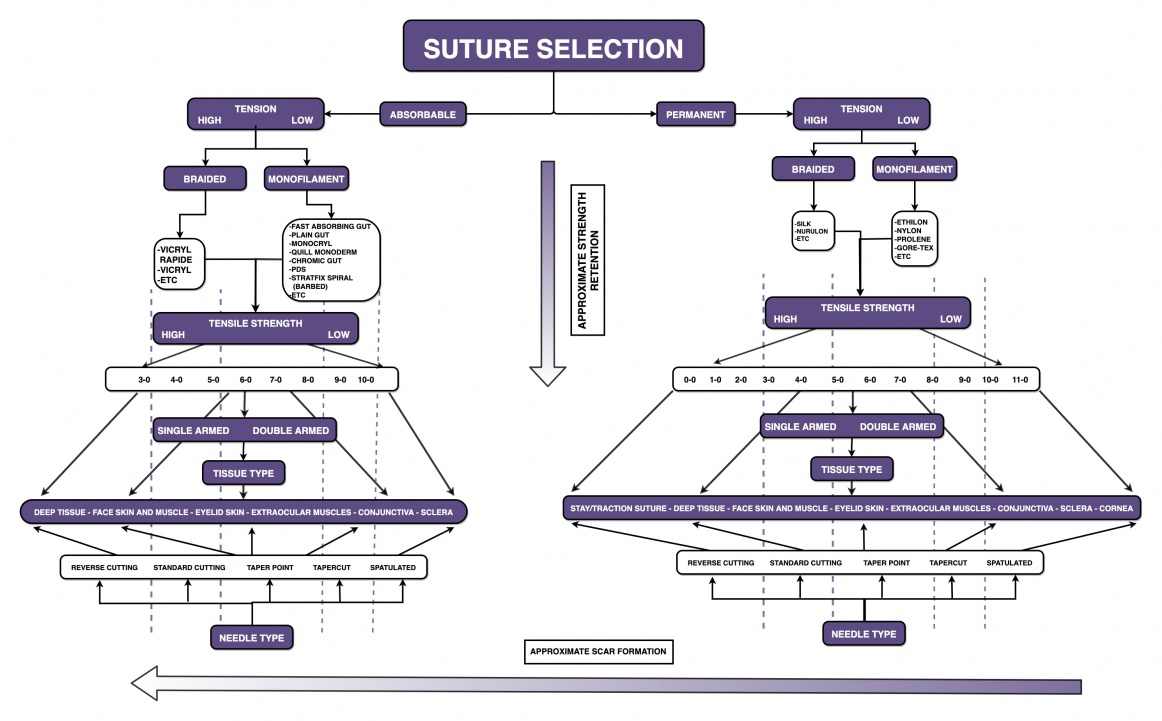

Suture Selection Flowchart

Suture Basics

As the numerical indicator increases, the width of the suture decreases, indicating a more fine thread composition. Based on the tissue characteristics and amount of tension one expects the suture to endure, the choice can be made for a specific suture thread size. Generally, the more fine the tissue, the less tension of the wound, and the minimization of scarring usually indicate the need for a finer, higher number sized suture. For wounds that have deep tissue, dense connective tissue, or will be under high tension and require good consistent apposition, a thicker, or lower number suture should be implemented.

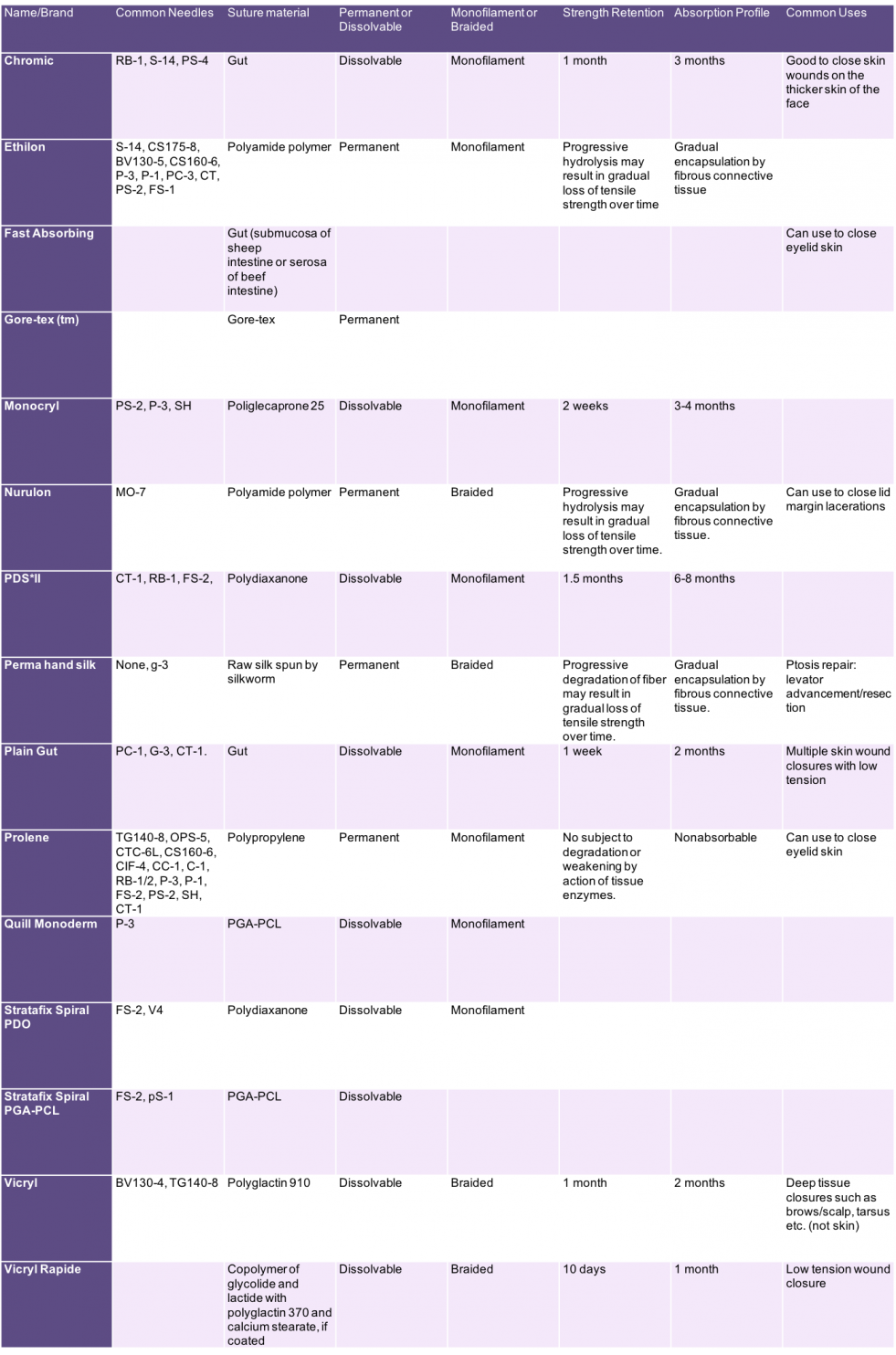

Suture Specifics

After choosing the size of suture that is appropriate, the composition of said thread is very important. The following table outlines some of the common materials that surgical sutures are made from along with some characteristics that may help clarify which suture composition will best achieve the desired surgical outcome.

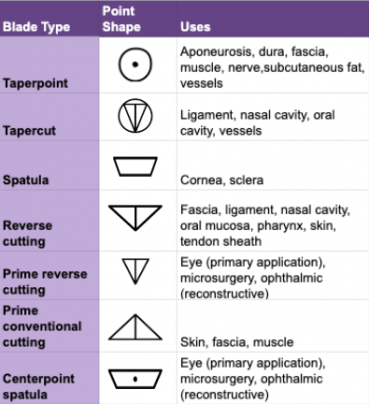

Needle Basics

The shape of the needle is very important when considering which suture to use. There are a variety of shapes as outlined below. It is important to know where the cutting action of the needle one chooses to employ is located on the needle itself. Every needle has a sharp tip, but in addition there can be sharpened sides that cut as well or even spatula shaped needles that help to dissect and maintain tissue planes. It is also important to know which side of the needle is blunt in order to avoid dissecting or cutting into tissue or in directions that are unintended. The following table has face-on drawings to help the surgeon visualize the needle tip and point as well as the sides that may be blunt or sharp. It is important to ensure the needle implemented for a surgical task is chosen to minimize tissue trauma, maximize wound healing and apposition or placement, and limit the need for multiple passes.

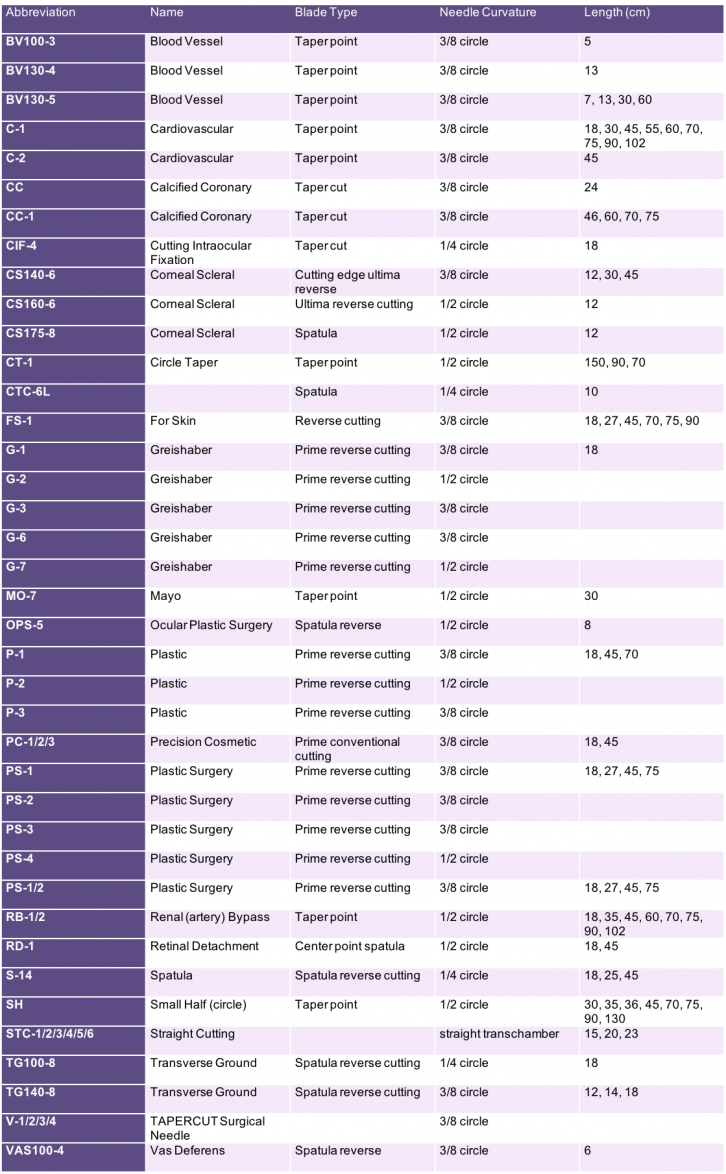

Needle Specifics

There are a plethora of options for needle types along with curvature arcs and lengths. Needles with larger curvatures are especially useful in tight surgical fields where delicate tissues need to be isolated without damaging neighboring structures. Smaller curvatures are useful for making shallow passes, and longer needles allow for more control and the grasping of more tissue. As always surgeon preference is the most important as many surgical techniques can be successfully implemented with more than one type of needle. Know what works best in the surgeon's hands specifically is the single most important factor in successful suture selection. The provided table is for reference, especially for the surgeon-in-training, in order to help explore what options are available for the variety of surgical applications faced by the modern ophthalmologist.

References

Dunn, David L, editor. Ethicon Wound Closure Manual. Johnson & Johnson, 2005.

Procedural Bootcamp. “21 Needles .” Dermatology for the NonDermatologist, Elsevier, 2018, camls-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/10.30am-Handout-Cherpelis-Needles-2018.pdf.

Ethicon Wound Closure Manual. Johnson & Johnson, 2019.

Lee, Wendy W. “A Primer on Sutures for Wound Closure in Ophthalmology.” OphthalmologyWeb, 11 Oct. 2013, www.ophthalmologyweb.com.

Rupp, Jason D. “Ophthalmic Suturing 101.” American Academy of Ophthalmology, 17 Aug. 2018, www.aao.org/young-ophthalmologists.

“Wound Closure Search: Ethicon Product Center: Ethicon EMEA.” Global, Johnson & Johnson, www.ethicon.com.