Choroidal Osteoma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Choroidal osteoma is a benign ossifying tumor characterized by mature bone replacing choroid. The condition is reported rarely, with only 61 patients seen at a major tertiary center in 26 years[1] However, asymptomatic patients with choroidal osteoma are typically not referred to a tertiary center, but rather are followed in community-based practice; one study reports 11 patients seen in a community based practice in a 14 year span[2]. Choroidal osteoma is unique as it affects otherwise healthy eyes.

Etiology

The etiology of the tumor is unknown. Factors implicated in its development, however, include inflammation, trauma, hormonal state, calcium metabolism, environment, and heredity. None of these factors appear to be either a sole, or an established, factor in causing patients to develop the condition. For instance, the hormonal hypothesis does not explain why males are affected by the condition or why these lesions can be observed in pre-pubertal patients. It has been postulated that choroidal osteoma is a choristoma (i.e., normal tissue arising at an abnormal location), but this explanation begs the question of why females are affected more frequently than males and why there is continuous development and growth of the lesion in adulthood. No consistency has been established with serum calcium, phosphate, or alkaline phosphatase levels[3].

Risk Factors

Choroidal osteoma is more commonly unilateral, but bilateral disease has been observed and the second eye can be affected later than the first one. The condition affects females more than males and typically first manifests in the teenage years or in the early twenties. No risk factors have been identified.

General Pathology

Choroidal osteoma was first described at the 1975 Meeting of Verhoeff Society. The case was that of a healthy 26 year old female patient who presented with paracentral scotoma and visual acuity of 20/20 in the both eyes. On exam she had a well-defined, slightly elevated, yellowish-white, subretinal tumor surrounding the nasal half of the optic disc in the left eye. A radioactive phosphorus (32P) test demonstrated a 270% uptake overlying the tumor and the eye was enucleated. Pathology revealed mature bone in choroid, marrow spaces filled with loose connective tissue and some dilated, thin-walled blood vessels. These marrow blood vessels communicated on the surface of the tumor, with a rich capillary network lying beneath Bruch's membrane and a degenerated retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)[4][5].

Pathophysiology

Choroidal osteoma is a benign ossifying tumor with mature bone replacing choroid. It is commonly juxtapapillary or peripapillary, but may extend to the macula. It is rare that it would be found only in the macula. It is yellow-white to orange-red in color with clumping of brown, orange, or gray pigment. The shape is commonly oval or round with well defined scalloped or geographic margins. Occasionally decalcification can occur and is characterized by thin, atrophic, yellow-gray regions with associated RPE atrophy[6][7]. Decalcification can occur spontaneously or as a result of laser photocoagulation or photodynamic therapy (PDT). Choroidal neovascular membranes (CNVM) can also develop.

Primary prevention

None.

Diagnosis

History

The patients report gradual onset of visual blurring, metamorphopsia, and visual field defects corresponding to the location of the tumor. They can be asymptomatic as well. The patients are most commonly females and in their late teens to early twenties.

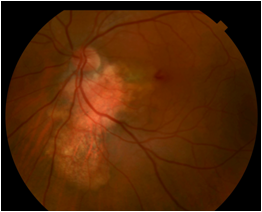

Physical examination

On fundus exam, choroidal osteoma appears as a juxtapapillary or peripapillary lesion that is yellow-white to orange-red in color with clumping of brown, orange, or gray pigment. It is oval or round with well defined scalloped or geographic margins. Thin, atrophic, yellow-gray regions with associated RPE atrophy represent areas of decalcification. Choroidal neovascularization can also be observed. CNVM appears as elevated gray-green areas associated with subretinal fluid and subretinal hemorrhage.

Signs

The description of choroidal osteoma given by J.D. Gass in 1978 still holds: 1) slightly and irregular elevated, yellow-white, juxtapapillary, choroidal tumor and well-defined geographic borders; 2) diffuse and mottled depigmentation of the overlying pigment epithelium; and 3) multiple small vascular networks on the tumor surface[4].

Symptoms

Frequently asymptomatic, choroidal osteomas can present as blurred vision, metamorphopsia, and visual field defects. A choroidal neovascular membrane can present as blurred vision and metamorphopsia in a previously stable eye. Decalcification in the subfoveal region is associated with poor vision.

Clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis is mainly clinical and relies on the appearance of the lesion on the examination of the posterior pole. A clinician should pay attention to areas of decalcification and be aware of the possibility of CNVM. Additional diagnostic studies are required to support the diagnosis.

Diagnostic procedures

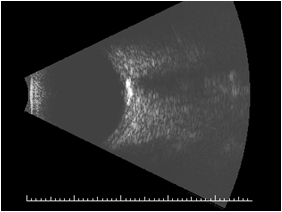

On ultrasound, the A scan shows a high intensity echo spike. The B scan shows slightly elevated, highly reflective choroidal mass with acoustic shadowing that gives an appearance of “pseudo-optic nerve”. The mass persists at lower scanning sensitivity after the other soft tissue echoes have disappeared[3].

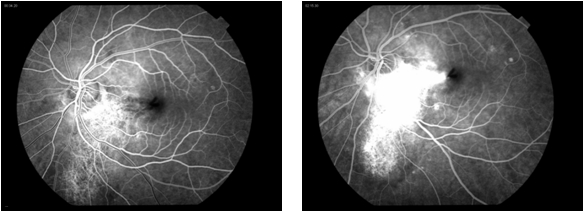

Fluorescein angiography shows early patchy hyperfluorescence with late diffuse staining. If CNVM is present, leakage is seen.

Optical coherence tomography can also be utilized in the cases of CNVM.

Choroidal osteoma can be seen on X-ray or CT scan – currently these modalities are rarely used for this condition[4][3] Choroidal osteoma appear hypointense in bothT1 and T2 weighted MRI images.

Pathology shows dense bony trabeculae with intertrabecular marrow and narrowed choriocapillaris. RPE is focally depigmented with clumps of pigment granules along Bruch’s membrane[3].

Laboratory test

No laboratory tests are currently recommended. No consistency has been observed with serum calcium, phosphate, or alkaline phosphatase levels.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes choroidal metastasis, sclerochoroidal calcifications, amelanotic choroidal melanoma, amelanotic choroidal nevus, choroidal Hemangioma, choroidal granuloma (TB, sarcoid), metastatic calcification, and dysmorphic calcification.

Management

Asymptomatic or stable choroidal osteoma can be observed.

For CNVM, surgical removal[8] and PDT[9][10][11] have been used in the past, as well as laser treatment[12][13][14][15].More recently, anti-VEGF treatments such an intravitreal ranibizumab and bevacizumab have been employed with success[16][17][18][19][20][21].

It has been shown that the margins of the choroidal osteoma that are decalcified have no tumor growth and display the stabilization of the tumor scar. Therefore, it has been proposed for the calcified extrafoveal osteoma, to use PDT at the edges to decalcify the tumor and prevent its growth and foveal involvement[22].

General treatment

General treatment is observation.

Medical therapy

Intravitreal therapy with anti-VEGF medications has been employed for CNVM.

Medical follow up

Observe for CNVM.

Surgery

Not indicated.

Surgical follow up

Not applicable.

Complications

Complications of choroidal osteoma include decalcification and CNVM.

Prognosis

At 10 years, 56% to 58% of patients have visual acuity less than or equal to 20/200. Long term poor visual acuity in patients with choroidal osteoma is associated with subretinal fluid, RPE alterations, and subretinal hemorrhage from choroidal neovascularization. Decalcification has also emerged recently as a new factor predictive of poor visual acuity[1].

Tumors show growth in 41% to 51% of patients at 10 years. Mean growth is approximated to be at the rate of 0.37 mm/yr. The factor found to be predictive of the tumor growth is absent overlying RPE alterations. Additionally, no tumor showed growth in the region of decalcification[1][23].

CNVM occurs in 31% to 47% of patients at 10 years. Factors predictive of CNVM are irregular tumor surface and subretinal hemorrhage[1][23].

Decalcification occurs in 46% of patients at 10 years. It is associated with irregular tumor surface. When decalcification occurs in the area of the macula, it is associated with poor visual acuity that is possibly due to photoreceptor atrophy[24]. However, a decalcified border of a tumor shows no growth on the margin with decalcification and results in the stabilization of the tumor scar[1].

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Shields CL, Sun H, Demirci H, Shields JA. Factors predictive of tumor growth, tumor decalcification, choroidal neovascularization, and visual outcome in 74 eyes with choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:1658-1666.

- ↑ Browning DJ. Choroidal osteoma: Observations from a community setting. Ophthalmology 2003;110:1327-1334.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Shields CL, Shields JA, Augsburger JJ. Choroidal osteoma. Surv Ophthalmol 1988;33:17-27.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 Gass JD, Guerry RK, Jack RL, Harris G. Choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1978;96:428-435.

- ↑ Williams AT, Font RL, Van Dyk HJ, Riekhof FT. Osseous choristoma of the choroid simulating a choroidal melanoma. association with a positive 32P test. Arch Ophthalmol 1978;96:1874-1877.

- ↑ Trimble SN, Schatz H. Decalcification of a choroidal osteoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1991;75:61-63.

- ↑ Trimble SN, Schatz H, Schneider GB. Spontaneous decalcification of a choroidal osteoma. Ophthalmology 1988;95:631-634.

- ↑ Foster BS, Fernandez-Suntay JP, Dryja TP, Jakobiec FA, D'Amico DJ. Clinicopathologic reports, case reports, and small case series: Surgical removal and histopathologic findings of a subfoveal neovascular membrane associated with choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:273-276.

- ↑ Battaglia Parodi M, Da Pozzo S, Toto L, Saviano S, Ravalico G. Photodynamic therapy for choroidal neovascularization associated with choroidal osteoma. Retina 2001;21:660-661.

- ↑ Singh AD, Talbot JF, Rundle PA, Rennie IG. Choroidal neovascularization secondary to choroidal osteoma: Successful treatment with photodynamic therapy. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:482-484.

- ↑ Blaise P, Duchateau E, Comhaire Y, Rakic JM. Improvement of visual acuity after photodynamic therapy for choroidal neovascularization in choroidal osteoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2005;83:515-516.

- ↑ Grand MG, Burgess DB, Singerman LJ, Ramsey J. Choroidal osteoma. treatment of associated subretinal neovascular membranes. Retina 1984;4:84-89.

- ↑ Gurelik G, Lonneville Y, Safak N, Ozdek SC, Hasanreisoglu B. A case of choroidal osteoma with subsequent laser induced decalcification. Int Ophthalmol 2001;24:41-43.

- ↑ Morrison DL, Magargal LE, Ehrlich DR, Goldberg RE, Robb-Doyle E. Review of choroidal osteoma: Successful krypton red laser photocoagulation of an associated subretinal neovascular membrane involving the fovea. Ophthalmic Surg 1987;18:299-303.

- ↑ Rose SJ, Burke JF, Brockhurst RJ. Argon laser photoablation of a choroidal osteoma. Retina 1991;11:224-228.

- ↑ Wadekar B, Tripathy K, Chawla R, Venkatesh P, Sharma YR, Vohra R. An 18-year-old female with unilateral painless vision loss. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2016;9(3):193.

- ↑ Song JH, Bae JH, Rho MI, Lee SC. Intravitreal bevacizumab in the management of subretinal fluid associated with choroidal osteoma. Retina 2010;30:945-951.

- ↑ Song MH, Roh YJ. Intravitreal ranibizumab in a patient with choroidal neovascularization secondary to choroidal osteoma. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1745-1746.

- ↑ Song WK, Koh HJ, Kwon OW, Byeon SH, Lee SC. Intravitreal bevacizumab for choroidal neovascularization secondary to choroidal osteoma. Acta Ophthalmol 2009;87:100-101.

- ↑ Narayanan R, Shah VA. Intravitreal bevacizumab in the management of choroidal neovascular membrane secondary to choroidal osteoma. Eur J Ophthalmol 2008;18:466-468.

- ↑ Ahmadieh H, Vafi N. Dramatic response of choroidal neovascularization associated with choroidal osteoma to the intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (avastin). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007;245:1731-1733.

- ↑ Shields CL, Materin MA, Mehta S, Foxman BT, Shields JA. Regression of extrafoveal choroidal osteoma following photodynamic therapy. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:135-137.

- ↑ Jump up to: 23.0 23.1 Aylward GW, Chang TS, Pautler SE, Gass JD. A long-term follow-up of choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:1337-1341.

- ↑ Shields CL, Perez B, Materin MA, Mehta S, Shields JA. Optical coherence tomography of choroidal osteoma in 22 cases: Evidence for photoreceptor atrophy over the decalcified portion of the tumor. Ophthalmology 2007;114:e53-8.