Cavernous Sinus Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease

Cavernous sinus syndrome (CSS) is a condition caused by any pathology involving the cavernous sinus which may present as a combination of unilateral ophthalmoplegia (cranial nerve (CN) III, IV, VI), autonomic dysfunction (Horner syndrome) or sensory CN V1- CN V2 loss.

Anatomy

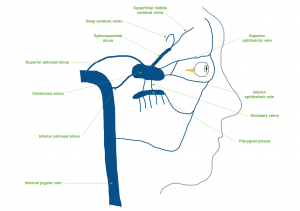

The venous drainage system of the head and face have a unique anatomy. The dural sinuses and the cerebral and emissary veins have no valves, which allows blood to flow in either direction (anterograde or retrograde) according to venous pressure gradients in the vascular system. This fact and the extensive direct and indirect vascular connections of the centrally located cavernous sinuses make them vulnerable to pathology at many sites.[1]

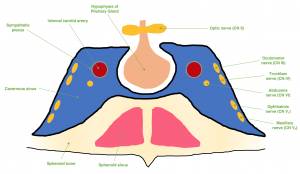

The cavernous sinuses are dural venous sinuses that communicate with one another. Each cavernous sinus is flanked laterally by the temporal bone of the skull and inferiorly by the sphenoid bone, with close proximity to the sphenoid sinuses. The pituitary gland sits within the sella turcica which exists medial to the cavernous sinus, and the optic chiasm lies superior to the cavernous sinus on the midline in close proximity to the pituitary gland.[2] (Figure 1)

Each cavernous sinus receives venous drainage from several structures within the face and eye. The superior and inferior ophthalmic veins drain anteriorly into the sinus. The superficial middle cerebral veins, deep cerebral veins (via the sphenoparietal sinus), and inferior cerebral veins drain into the cavernous sinus as well. Inferiorly, the cavernous sinus drains to the pterygoid plexus and posteriorly, it communicates with the superior and inferior petrosal sinuses. Both drainage systems ultimately converge at the internal jugular vein.[3] (Figure 2)

The presence of important CNs and blood vessels makes the cavernous sinus a unique site for potential pathology. The internal carotid artery (ICA) traverses the carotid sinuses bilaterally. Post-ganglionic, third-order sympathetic fibers (Horner syndrome) run on the ICA and CN VI and then CN V1. CN III, CN IV, CN V1, and CN V2 are all tethered to the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus, but CN VI lies freely inferolateral to the ICA and medially to the other CNs. CN II does not travel within the cavernous sinus, but is closely associated superomedially.[2]

Etiology

A CSS is caused by any pathology or lesion present within the cavernous sinus that disrupts the function of other anatomical structures. The most common cause of CSS is mass effect from tumor. Other common causes of CSS include trauma and self-limited inflammatory disease. Less common causes are vascular etiologies and infections.[4]

One important infectious etiology of CSS includes cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST), which may present initially to an ophthalmologist and requires urgent management due to its life-threatening prognosis. Septic CST is typically seen as a complication of a facial infection, such as sinusitis or cellulitis. Due to the valveless nature of the facial veins, the sinuses are vulnerable to stagnation and poor drainage in the setting of severe infection, causing the formation of a thrombus. The thrombus can then cause damage locally or travel to the brain, causing stroke-like symptoms or encephalitis and meningitis.[2] Specific etiologies of CSS are listed in Table 1.

| Cause | Clinical Features |

|---|---|

| Tumor[5] | Meningioma, chordoma, neuroma, pituitary adenoma, metastases, lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, chondrosarcoma, hemangioma, neuroblastoma |

| Inflammatory Disease[5] | Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, sarcoidosis |

| Trauma[4] | Basal skull fracture, operative trauma to cavernous sinus after skull base surgery |

| Vascular[5] | Intracavernous aneurysm, carotid-cavernous fistula, cavernous sinus thrombosis |

| Infection[6] | Mucormycosis, aspergillosis, actinomycosis, nocardiosis, mycobacterium, herpes zoster |

Pathophysiology

The pathomechanism of CSS is characterized by the compression and dysfunction of the structures within the cavernous sinus. The cavernous sinus is a fixed space limited by bony structures, so any pathology within the sinus has the ability to compress internal structures, causing ophthalmoplegia and facial sensory changes. Additionally, due to the postganglionic sympathetic plexus travelling on the ICA and CN VI, damage can cause an ipsilateral loss of sympathetic tone presenting as a Horner syndrome. The combination of CN VI palsy and ipsilateral Horner syndrome localizes the lesion to the cavernous sinus (Parkinson sign).[7]

Diagnosis

- Clinical Presentation[2][8]

- The common clinical findings of CSS are as follows:

- Total/partial ophthalmoplegia

- CN III palsy – partial or total loss of elevation, depression and adduction of ipsilateral eye

- CN IV palsy – partial or total loss of abduction and depression of ipsilateral eye

- CN VI palsy – partial or total loss of abduction of ipsilateral eye

- Facial sensory loss

- CN V1 loss – partial or total loss of sensation in ophthalmic distribution

- CN V2 loss – partial or total loss of sensation in maxillary distribution

- Horner syndrome – loss of sympathetic tone due to damage of sympathetic plexus

- Proptosis and chemosis – due to increased pressure within cavernous sinus

- Presence of fever, tachycardia, hypotension, rigors, nuchal rigidity, altered mental status should cause concern for CST[1]

- Total/partial ophthalmoplegia

- It is important to note that CSS does not always include all these findings. CSS may present with any combination of these features.

- The common clinical findings of CSS are as follows:

- Diagnostic Procedures

- The diagnosis of CSS is initially suspected on clinical grounds. However, further workup is needed to determine the underlying etiology of CSS. Due to wide array of potential causes, workup can be challenging and extensive. Imaging of the head and orbit and laboratory tests play a role in confirming the diagnosis.

- The patient’s history should be clinically correlated with the physical examination findings, and the appropriate diagnostic tests should be performed accordingly, to reach a diagnosis efficiently. Blood tests, such as complete blood count (CBC) and blood cultures, can be used to assess for underlying infection. Serum studies, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are recommended to evaluate for an underlying inflammatory process. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits with contrast and magnetic resonance venography (MRV) is preferred to determine the presence of a tumor, trauma, inflammation, or CST. Imaging with computed tomography (CT) of the brain and orbits or CT venography can be done to help adjudicate the presence of trauma or vascular process.[8][9]

Management [2]

The management of CSS depends on its underlying etiology. As such, treatment is not standardized. The most common cause of CSS is tumor, but due to the variability of tumor pathology, treatment can vary. Surgery and/or radiotherapy are potential options for treatment of a tumor. Traumatic cases may self-resolve or may require orbital surgical decompression to repair severe damage and cases with significant edema. For the management of inflammatory disease, the use of systemic glucocorticoid therapy is often effective. Vascular causes such as fistulas and aneurysms are often amenable to interventional radiology procedures such as balloon or coil embolization.[10] Patients with an infectious cause should receive the appropriate treatment per IDSA guidelines.[11]

Causes such as septic CST that may be acutely life-threatening must be recognized and managed emergently. Intravenous antibiotics must be started immediately for the treatment of an underlying infection. Though controversial, anticoagulation is recommended. Otolaryngology should be consulted to evaluate for the need for surgical drainage of the primary infection.[2]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Ebright JR, Pace MT, Niazi AF. Septic Thrombosis of the Cavernous Sinuses. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(22):2671–2676. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.22.2671

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Tamhanker MA. Eye Movement Disorders: Third, Fourth, and Sixth Nerve Palsies and Other Causes of Diplopia and Ocular Misalignment. In: Liu, Volpe, and Galetta’s Neuro-Ophthalmology. 3rd ed. ; :489-547.

- ↑ Waxman SG. Vascular Supply of the Brain. In: Clinical Neuroanatomy, 28e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; . http://neurology.mhmedical.com.srv-proxy2.library.tamu.edu/content.aspx?bookid=1969§ionid=147037147. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Keane, James R. "Cavernous sinus syndrome: analysis of 151 cases." Archives of Neurology 53.10 (1996): 967-971.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Fernández, Susana, et al. "Cavernous sinus syndrome: a series of 126 patients." Medicine 86.5 (2007): 278-281.

- ↑ Lubomski, Michal, et al. "Actinomyces cavernous sinus infection: a case and systematic literature review." Practical neurology 18.5 (2018): 373-377.

- ↑ Harris FS and Rhoton, Jr. AL. Anatomy of the cavernous sinus: A microsurgical study. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1976; 45: 169-180.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Goyal, Pradeep, et al. “Orbital apex disorders: Imaging findings and management.” The Neuroradiology Journal. 31.2 (2018): 104-125.

- ↑ Razek, AAK Abdel and Castillo, M. “Imaging Lesions of the Cavernous Sinus.” American Journal of Neuroradiology. 30 (2009): 444-452.

- ↑ Das, Sunit, Bendock BR, et al. “Return of vision after transarterial coiling of a carotid cavernous sinus fistula: case report.” Surgical Neurology. 66 (2006): 82-85.

- ↑ IDSA Practice Guidelines. Infectious Diseases Society of America. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/practice-guidelines/#/name_na_str/ASC/0/+/. Accessed March 30, 2020.