Birdshot Retinochoroidopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

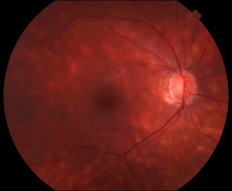

Birdshot Chorioretinopathy (BSCR, also known as birdshot retinochoroidopathy, vitiliginous chorioretinitis, or simply birdshot uveitis) is a chronic, bilateral, posterior uveitis with characteristic multifocal cream-colored choroidal lesions in the posterior pole and mid-periphery.[1] The lesions are often clustered around the optic nerve and posterior pole, radiating towards the periphery in a pattern similar to the gunshot spatter from birdshot. These lesions are ¼ to ½ optic disc diameter and can be diffuse, macula predominant, macula sparing, or asymmetric. The early stage of the disease is characterized by retinal vascular leakage, which is later followed by the prominent birdshot lesions described above. The late stage of disease involves cystoid macular edema (84% in BSCR vs. 30% in other types of uveitis)[2], vascular attenuation, RPE changes, optic nerve atrophy, and subretinal neovascularization.

History

Birdshot uveitis was first described in 1949. The disease has been called:

- ‘la chorioretinite en tache de bougie’’ (Candle Wax Spot Chorioretinopathy) by Drs. Franceschetti and Bable in 1949

- Birdshot Retinochoroidopathy by Drs. Ryan and Maumenee in 1980

- Vitiliginious Chorioretinitis by Dr. Gass in 1981

- Salmon Patch Choroidopathy by Dr. Aaberg in 1981

- Rice Grain Chorioretinopathy by Dr. Amalric and Cuq in 1981

Risk Factors

Birdshot uveitis primarily affects individuals of Northern European descent aged 40 to 60.[3] It has the strongest human class I MHC correlation with any disease, with 80-98% of patients being HLA-A29 positive (vs. 7% in the general population)[4]. The presence of the gene is associated with a 50-224 times greater relative risk of developing the disease[5].

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology is unclear, though it is primarily thought to be a T-cell mediated autoimmune disorder. It has been hypothesized to be due to response to retinal S antigens; however, one study found no significant difference in the serum titers of anti-S Ag between controls and patients with Birdshot uveitis[6]. An alternate theory is that an infectious agent stimulates T lymphocytes to express self-peptides.

Biopsy of an HLA-A29 positive eye has revealed multiple foci of lymphocytes at various levels of choroid, surrounding retinal blood vessels, and prelaminar optic nerve head.[7] The inflammatory exudates may infiltrate the choroidal cleavage plane, undergo fibrosis, fuse the choroidal interstitium, and result in atrophic lesions.

Diagnosis

Signs and Symptoms

The most common symptoms include decreased vision (68%), floaters (29%), nyctalopia (25%), dyschromatopsia (20%), glare (19%), and photopsia (17%)[2]. Vision loss is more notable in later stages. Although BSCR is a primarily ocular disease, there have been some reported associations with systemic hypertension, skin malignancy, hearing loss, vitiligo, and mood disorders. The symptoms can be vague, and sometimes the patient notes that 'something is not right'; therefore, often there can be significant delay in the diagnosis of this condition.[8]

Physical Examination

On exam, the presence of mild to no anterior chamber inflammation and absent to moderate vitritis is expected. Retinal vascular leakage may be the only noticeable finding early on, while the characteristic multifocal cream-colored or yellow-orange, oval or round lesions emerge from around the optic nerve later in the disease course. Advanced stages of BSCR may be accompanied by cystoid macular edema, vascular attenuation, subretinal neovascularization, and optic nerve atrophy.

Differential Diagnoses

Autoimmune (or Presumed Autoimmune)

- Sarcoidosis

- Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy (APMPPE)

- Multiple Evanescent White Dot Syndrome (MEWDS)

- Multifocal Choroiditis and Panuveitis Syndrome (MCP)

- Punctate inner choroiditis (PIC)

Infectious

- Tuberculosis

- Syphilis

Masquerade

- Primary CNS Lymphoma

Diagnostic Criteria

In 2021, the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group updated classification criteria for BSCR using a machine learning model based on 1,068 cases of posterior uveitis, including 207 cases of BSCR. [9]

Criteria 1- 3 or 4:

- Characteristic bilateral multifocal choroiditis on ophthalmoscopy: multifocal cream-colored or yellow-orange, oval or round choroidal lesions (“birdshot spots”)

- Absent to mild anterior chamber inflammation: absent to mild anterior chamber cells, no keratic precipitates, and no posterior synechiae

- Absent to moderate vitritis OR

- Multifocal choroiditis with Positive HLA-A29 test AND either of the following:

- Characteristic “birdshot” spots (multifocal cream-colored or yellow-orange, oval or round choroidal lesions) on ophthalmoscopy

- Characteristic indocyanine green angiogram (multifocal hypofluorescent spots) without characteristic “birdshot” spots on ophthalmoscopy

The following exclusions apply: 1. Positive serologic test for syphilis using a treponemal test 2. Evidence of sarcoidosis (either bilateral hilar adenopathy on chest imaging or tissue biopsy demonstrating non-caseating granulomata) 3. Evidence of intraocular lymphoma on diagnostic vitrectomy or tissue biopsy

Testing

While BSCR is diagnosed clinically, diagnostic testing and multi-modal imaging can play an important role in identifying patients who require further evaluation and monitoring of treatment.

Laboratory tests:

Initially, common causes of uveitis should be considered and ruled out. Complete blood count (CBC), RPR/FTA-ABS, ACE, lysozyme chest X-ray, and tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) or QuantiFERON Gold testing may be indicated.

Ancillary tests:

- Visual Electrodiagnostic Testing: In earlier stages of BSCR, a disproportionate decrease in b-wave amplitude relative to a-wave amplitude may be present. With progression of disease changes to inner retinal function of cone and rod systems presents with a delayed cone mediated 30 Hz flicker on electroretinograms, which is the most sensitive method for the assessment and monitoring of BSCR using electrodiagnostic testing.[10]

- Fluorescein angiography (FA) may reveal macular edema and hyperfluorescent choroidal lesions. However, indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) is more sensitive compared to FA and fundoscopy in revealing the choroidal lesions, especially early in the course of disease .[11]

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT) can also demonstrated the choroidal lesions and macular edema. It can be used to quantify retinal thinning and loss of the third highly reflective band (HRB), both of which have been associated with worse visual outcomes.[3] [12]

- OCT angiography can identify abnormal flow signals, similar to those seen on ICGA.[13] Hypo-reflectivity in the macular and peripapillary regions on enhanced depth OCT (ED-OCT), which enables the analysis of deeper choroidal levels, is another common finding in BSCR, and it has been reported in up to 64% of patients.[14]

- Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) with peripapillary confluent hypo-autofluorescence is shown to be present in 73% of eyes and is associated with chronicity and severity of BSCR.[15] Linear hypo-autofluorescence streaks along retinal vessels and an arcuate pattern of hypo-autofluorescence at the posterior pole have also been reported.[15][16]

- Visual Field Testing: Patients can experience significant visual field defects despite well-preserved central VA, including diffuse constriction, paracentral scotomas, and blind spot enlargement.

Management and Outcomes

Treatment

The mainstay treatment in BSCR is corticosteroids. Co-administering immunosuppressive therapy with steroids has been shown to be advantageous in preserving visual function and reducing the adverse effects associated with high doses of corticosteroids, when compared to corticosteroid therapy alone.[17] If left untreated, most patients will experience a progressive decline in visual function.

Steroids

- Oral steroids: less than 15% remained symptom-free on <20mg/d

- Local steroid injection: often used in those who have persistent macular edema despite systemic therapy or those who cannot tolerate or inadequately respond to systemic therapy. In BSCR particularly, steroid implants have been associated with a robust IOP response compared to other types of uveitis with up to 40% of patient requiring trabeculectomy surgery and all patient requiring cataract surgery. [18][19]

Immunomodulatory Therapy (IMT)

- Calcineurin inhibitors, which inhibit T-cell signaling, and anti-metabolites are most often the first IMTs considered.

- Mycophenolate mofetil has been shown to be more effective compared to other antimetabolites in treating posterior uveitis and panuveitis.[20] However, a randomized clinical trial of methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil has revealed statistically insignificant higher treatment success in methotrexate for posterior and panuveitis in general.[21]

Biologics

If patients fail to respond to conventional IMT, escalation to treatment with biologics is indicated. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors, such as infliximab and adalimumab, have shown effectiveness in treating some forms of refractory uveitis, including BSCR.[22][23][24] A study of adalimumab demonstrated improvement of visual acuity and successful tapering of concomitant IMT; however, complete remission of disease is challenging with adalimumab alone.[24] Successful use of other classes of biologics, such as tocilizumab, have been reported, but current evidence for their use in BSCR is limited. [25]

Treatment Success

Treatment success with immunosuppression after one year of therapy is estimated to be 67% to 90%.[26] Single or dual agent immunosuppression has been successfully used to control BSCR while sparing steroid use to minimize systemic side effects. Steroid sparing, defined as successfully tapering Prednisone dose to < 7.5mg, is generally considered safe for long term use and is possible within 6 months. A recent study suggests that up to 90% of patients can achieve steroid sparing, and as many as 75% of patients can completely discontinue steroid use. [26] However, over 40% of patients can have reactivation of BSCR during tapering, requiring the use of a second IMT. Once steroid tapering is achieved, it may still be necessary to continue treatment with higher doses of IMT for at least 2 years before tapering these immunosuppressive agents to decrease the risk of relapse after remission induction.[26]

Visual Prognosis

Studies have demonstrated a robust correlation between VA at onset and long-term visual prognosis.[2] Approximately 97.5% of patients may have some visual symptom at baseline, with 44% having an abnormal visual field and 50-76% with abnormal EOG[3][27]. Without treatment, 16-22% of patients will developed VA ≤ 20/200 over 10 years (versus 4% in other types of uveitis). With the use of IMT, visual acuity remained stable or improved in 78.6-89.3% while visual fields improved from a loss of 56-107° per year to a gain of 30-53° per year.[17][28]

References

- ↑ Bousquet E, Duraffour P, Debillon L, Somisetty S, Monnet D, Brézin AP. Birdshot Chorioretinopathy: A Review. J Clin Med. 2022 Aug 16;11(16):4772. doi: 10.3390/jcm11164772.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 Rothova A, Berendschot TT, Probst K, van Kooij B, Baarsma GS. Birdshot chorioretinopathy: long-term manifestations and visual prognosis. Ophthalmology. 2004 May;111(5):954-9. PubMed PMID: 15121374.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 Monnet D, Brézin AP, Holland GN, et al. Longitudinal Cohort Study of Patients With Birdshot Chorioretinopathy. I. Baseline Clinical Characteristics. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(1):135-142. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.067

- ↑ Kiss S, Anzaar F, Stephen Foster C. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2006 Spring;46(2):39-55.

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. "Birdshot Retinochoroidopathy." Section 9: Intraocular Inflammation and Uveitis. Singapore, 2011-2012. 152-155.

- ↑ LeHoang P, Cassoux N, George F, Kullmann N, Kazatchkine MD. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) for the treatment of birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2000 Mar;8(1):49-57. PubMed PMID: 10806434.

- ↑ Gaudio PA, Kaye DB, Crawford JB. Histopathology of birdshot retinochoroidopathy.Br J Ophthalmol. 2002 Dec;86(12):1439-41.

- ↑ Taylor S, Menezo V. Birdshot uveitis: current and emerging treatment options. Clin Ophthalmol. Published online December 2013:73. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S54832

- ↑ Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Development of classification criteria for birdshot chorioretinitis. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(11):1624-1630. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.05.028.

- ↑ Sobrin L, Lam BL, Liu M, Feuer WJ, Davis JL. Electroretinographic Monitoring in Birdshot Chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(1):52.e1-52.e18. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.01.053

- ↑ Fardeau C, Herbort CP, Kullmann N, Quentel G, LeHoang P. Indocyanine green angiography in birdshot chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(10):1928-1934. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90403-7

- ↑ Shields CL, Materin MA, Walker C, Marr BP, Shields JA. Photoreceptor Loss Overlying Congenital Hypertrophy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium by Optical Coherence Tomography. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(4):661-665. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.10.057

- ↑ Pepple KL, Chu Z, Weinstein J, Munk MR, Van Gelder RN, Wang RK. Use of En Face Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Identifying Choroidal Flow Voids in 3 Patients With Birdshot Chorioretinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(11):1288-1292.

- ↑ Böni C, Thorne JE, Spaide RF, et al. Choroidal Findings in Eyes With Birdshot Chorioretinitis Using Enhanced-Depth Optical Coherence Tomography. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2016;57(9):OCT591. doi:10.1167/iovs.15-18832

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Böni C, Thorne JE, Spaide RF, et al. Fundus Autofluorescence Findings in Eyes With Birdshot Chorioretinitis. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2017;58(10):4015. doi:10.1167/iovs.17-21897

- ↑ Koizumi H, Pozzoni MC, Spaide RF. Fundus Autofluorescence in Birdshot Chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(5):e15-e20. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.01.025

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Kiss S, Ahmed M, Letko E, Foster C. Long-term Follow-up of Patients with Birdshot Retinochoroidopathy Treated with Corticosteroid-Sparing Systemic Immunomodulatory Therapy. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(6):1066-1071.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.12.036

- ↑ Burkholder BM, Wang J, Dunn JP, Nguyen QD, Thorne JE. POSTOPERATIVE OUTCOMES AFTER FLUOCINOLONE ACETONIDE IMPLANT SURGERY IN PATIENTS WITH BIRDSHOT CHORIORETINITIS AND OTHER TYPES OF POSTERIOR AND PANUVEITIS. Retina. 2013;33(8):1684-1693. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e31828396cf

- ↑ Jaffe GJ, Martin D, Callanan D, Pearson PA, Levy B, Comstock T. Fluocinolone Acetonide Implant (Retisert) for Noninfectious Posterior Uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(6):1020-1027. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.02.021

- ↑ Galor A, Jabs DA, Leder HA, et al. Comparison of Antimetabolite Drugs as Corticosteroid-Sparing Therapy for Noninfectious Ocular Inflammation. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(10):1826-1832. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.026

- ↑ Rathinam SR, Babu M, Thundikandy R, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Methotrexate and Mycophenolate Mofetil for Noninfectious Uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(10):1863-1870. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.023

- ↑ Artornsombudh P, Gevorgyan O, Payal A, Siddique SS, Foster CS. Infliximab Treatment of Patients with Birdshot Retinochoroidopathy. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(3):588-592. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.05.048

- ↑ Suhler EB. A Prospective Trial of Infliximab Therapy for Refractory Uveitis: Preliminary Safety and Efficacy Outcomes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(7):903. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.7.903

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 Huis in het Veld PI, van Asten F, Kuijpers RWAM, Rothova A, de Jong EK, Hoyng CB. ADALIMUMAB THERAPY FOR REFRACTORY BIRDSHOT CHORIORETINOPATHY. Retina. 2019;39(11):2189-2197. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002281

- ↑ Muselier A, Bielefeld P, Bidot S, Vinit J, Besancenot JF, Bron A. Efficacy of Tocilizumab in Two Patients with anti-TNF-alpha Refractory Uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011;19(5):382-383. doi:10.3109/09273948.2011.606593

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 26.2 Crowell EL, France R, Majmudar P, Jabs DA, Thorne JE. Treatment Outcomes in Birdshot Chorioretinitis. Ophthalmol Retina. 2022;6(7):620-627. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2022.03.003

- ↑ Gasch AT, Smith JA, Whitcup SM. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999 Feb;83(2):241-9.

- ↑ Thorne JE, Jabs DA, Kedhar SR, Peters GB, Dunn JP. Loss of visual field among patients with birdshot chorioretinopathy. Am Jo Ophthalmol. 2008 Jan;145(1):23-28. Epub 2007 Nov 12