Application of Stem Cells for Regenerative Therapy in Cornea

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

The cornea is the eye's major protective barrier and accounts for approximately two- thirds of the eye's total refractive power. It consists of three layers that have different embryonic origins: the epithelial layer develops from the surface ectoderm, whereas the stroma and the endothelium origin from neural crest cells (mesenchymal tissue).[1] Experimental studies have shown that diverse types of stem cells are located in each layer.[2][3][4]

Corneal blindness due to compromised corneal transparency is a major cause of blindness. In the past few years, intensive research has focused on corneal stem cells as a source of regenerative cell-based therapy. This review summarizes the current knowledge on corneal epithelial, stromal, and endothelial stem cells and alternative source of stem cells in regenerative therapy of the cornea.

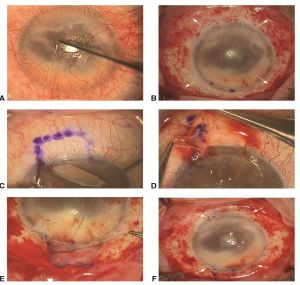

Types of limbal stem cell transplants[5]

Limbal Autograft

- Conjunctival- limbal autograft (CLAU)- large free conjunctival graft (90-300 degrees, classically two 60 degrees grafts) harvested from the healthy eye.

- Cultured limbal epithelial transplantation (CLET)- limbal cell sheets are cultured from limbal biopsies (2x2mm) of the healthy eye or remaining healthy limbus of an eye with partial limbal stem cell deficiency and expanded ex vivo.

- Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET)- a small biopsy (2x2mm) from the limbus of the healthy eye is divided (8-12 pieces) and distributed over the cornea of the affected eye using a amniotic membrane scaffold .

Limbal Allografts- require long- term systemic immunosuppression

- Keratolimbal allografts (KLAL) "Cincinnati Procedure"- Two donor corneoscleral rims are used to restore a 360 degree limbus.

- Living- related conjunctival allograft (LR-CLAL) - Limbal and conjunctival tissues are harvested from living relatives. HLA- typing may be helpful.

- Allogenic SLET

Ocular Source of Stem Cells

Limbal Epithelial Stem Cells (LESCs)

The limbus is classically known as the location for epithelial stem cells. Anatomically, small clusters of LESCs are located within the basal epithelial papillae of the Palisades of Vogt.[6] The Palisades of Vogt are radially orientated fibrovascular ridges that are more densely located at the superior and inferior limbal borders.[7] Majo et al[8] challenge the concept of exclusiveness of LESCs in the limbal area. They reported mouse corneal epithelium could be serially transplanted, were self-maintained, and contained oligopotent stem cells with the capacity to generate goblet cells if provided with a conjunctival environment. Dr. Tseng et al[9] countered this study, since their findings were inconsistent with many known growth, differentiation, and cell migration properties of the anterior ocular epithelia. However, Chang et al[10] showed that the capacity for human epithelial cell proliferation and migration in the center of cornea was similar to the periphery even after ablation of the limbus, at least in the first twelve hours after injury.

Ex vivo expansion and transplantation of LESC

Ex vivo expansion of limbal stem cells from a small biopsy and its subsequent transplantation is a choice of treatment for limbal stem cell deficiency.

The clinical use of this method was first described by Pellegrini et al[11] in 1997. Subsequently, several reports with a variety of cell culture protocols were published that showed the effectiveness of this method.[12]

[13]

[14][15][16][17][18]

Most studies used murine 3T3 feeder layer and bovine serum as a prerequisite for ex vivo expansion. However, murine feeder layer has the possibility of xeno-contamination of limbal cells and zoonotic diseases.[19]

As cell-based therapy has progressed toward application in clinical trials, its regulation has become an important concern. There are currently no regulations regarding this procedure, but the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has proposed new policies requiring the registration of all tissue banks, expanded screening and testing, and the introduction of practices similar to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP). The level of regulatory compliance in previously published studies is not known.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18] Shortt et al[20] and Kolli et al [21] reported clinical results of the use of ex vivo LESCs cultured in compliance with GMP standards and the European Union Tissues and Cells Directive. They used suspension culture method and amniotic membrane as carrier without a 3T3 fibroblast feeder layer. Kolli et al[21] treated eight eyes of eight consecutive patients by unilateral total LSCD with ex vivo expanded autologous LSC transplant on human amniotic membrane (HAM) with a mean follow-up of 19 months. Postoperatively, satisfactory ocular surface reconstruction with a stable corneal epithelium was obtained in all eyes (100%) and best corrected visual acuity improved in five eyes and remained unchanged in three eyes. Shortt et al[20] used allogeneic (7 eyes) or autologous (3 eyes) corneal LESCs that were cultured on human amniotic membrane with clinical follow-up to 13 months. They reported a success rate of 60% (autografts 33%, allografts 71%) defined as the restoration of a more normal corneal phenotype on impression cytology and the appearance of a regular hexagonal basal layer of cells on corneal confocal microscopy.

Corneal Stroma and Endothelium Stem Cells

In the past decade, small population of stem cells has been identified in many mesenchymal tissues. Isolation of bovine, mice, and rabbit stromal progenitor cells was first performed per clonal growth and expression of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) markers in attachment-free cultures.[3][4][22]

Indeed, identification and isolation of stromal stem cells might be a valuable resource for bioengineered stroma or cell-based therapy particularly for corneal scar, as Du et al[23] showed injection of human corneal stem cell in lumican-null mice can restore corneal transparency.

Several studies have shown the presence of human corneal endothelium (CE) precursors by a sphere-forming assay. Yokoo et al[24] reported that human CE from donor corneas formed primary and secondary sphere colonies and expressed neural and mesenchymal proteins. Yamagami et al.[25] identified original tissue-committed precursors with limited self-renewal capacity from human corneal stromal (HCS) cells and human corneal endothelial (HCE) cells with sphere-forming assay using serum-free medium containing growth factors in floating culture. They showed that the rate of primary sphere formation from peripheral HCS cells was 1.5-fold greater than in the paracentral cornea and 4-fold greater than in the central cornea. The rate of primary sphere formation by peripheral HCE cells was 4-fold greater than in the central cornea. Therefore, all HCS and HCE cells contain a significant number of precursors, but the peripheral cells have a density of precursors higher than that of the central cells.

Alternative Source of Stem cells

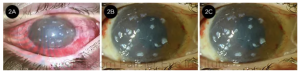

Total bilateral corneal limbal epithelial stem cell deficiency (LSCD) cannot be treated with the surgical transplantation of autologous limbus or cultured autologous limbal epithelium. Transplantation of allogenic limbal epithelium is possible but it requires systemic immunosuppression and has a success rate that tends to decrease gradually over time (graft survival rate of 40% at 1 year and 33% at 2 years).[26]Clinical application of cultured stromal and endothelial stem cells has not been used because of complexity in isolation of enough cells and lack of optimized culture medias. Therefore, finding an alternative source of cells, both ocular and non-ocular is essential, a source that is easy accessible and from which a large quantity of cells is obtainable.

Conjunctival Epithelial Stem Cells

Pellegrini et al[27] in a detailed in vitro study revealed a uniform distribution of presumed stem cells in the bulbar and forniceal conjunctiva. They showed that epithelial and goblet cells of the conjunctiva are derived from a common progenitor with high proliferative capacity that gives rise to goblet cells at least twice during their life cycle. Qi et al[28] showed that the expression of markers in the human basal cells of bulbar conjunctival epithelium is similar to corneal epithelium. In patients, cultured conjunctival epithelial cells containing stem cells, have been used to successfully treat patients with ocular surface damage. [29] The problem is most of LSCD patients do not have a healthy conjunctiva to be used for cell culture and transplantation.

Dental Pulp Stem Cells

Kerkis et al[30] isolated immature dental pulp SCs from human deciduous teeth, which were named human immature dental pulp stem cells (hIDPSC). These cells were shown to express both mesenchymal stem cell markers and human embryonic stem cell markers and to differentiate into derivative cells of the three germinal layers. The same group in another study[31] demonstrated that hIDPSCs express markers of limbal stem cells and are capable of reconstructing the ocular surface after total limbal stem cell deficiency in rabbits. There is no study showing the effectiveness of this method in human subjects.

Hair Follicle Stem Cells

Several research groups have focused on using hair follicle (HF) as a source of adult SC for regenerative medicine. It was shown that the HF contains mesenchymal SC in the dermal papilla and connective tissue sheath, which possess the potential to differentiate into several cell lineages including hematopoietic, adipogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic, myogenic, and neurogenic[32]. Meyer-Blazejewska et al[33] demonstrated that HFSCs were capable of being reprogrammed ex vivo into cells of the corneal epithelial phenotype using conditioned media harvested from corneal and limbal stromal fibroblasts. In a recent study[34], they provided evidence demonstrating that HFSCs can go beyond their lineage boundaries and terminally differentiate into a different epithelial cell phenotype in vivo when grafted into a specific niche microenvironment in murine model of limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD). There is lack of effectiveness of this method in clinical trials.

Oral mucosal epithelium

Oral mucosal SCs are also located in the basal layer and express LSC markers and can be reprogrammed into corneal epithelial-like cells.[35] Oral mucosal epithelial cells have the capacity to engraft onto the ocular surface and survive after transplantation in patients with LSCD following alkali injures.[36] and is considered to be safe, despite the risk of contamination. Cultured autologous oral mucosal epithelial cell sheet (CAOMECS) is a transparent, resistant, viable, and rapidly bioadhesive cell sheet, cultured with the UpCell-Insert technology (CellSeed, Inc., Tokyo, Japan)[37], which allows for grafting onto the patient’s corneal stroma without suturing. It has therefore been proposed as an alternative treatment for total bilateral LSCD. Burillon et al[26] performed a clinical trial to confirm the safety and efficacy of CAOMECS with a prospective, noncomparative study in 26 eyes of 25 patients. Two patients experienced serious adverse events, one with corneal perforation and the other with massive graft rejection. The treatment was found to be effective in 16 of 25 patients at 360 days after grafting. Of the 23 patients who completed follow-up at 360 days, 22 had no ulcers and 19 showed a decrease in the severity of the punctate epithelial keratopathy.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)

MSCs have been identified from bone marrow, umbilical cord, amniotic membrane, and adipose tissue. They are multi-potent, express mesenchymal and embryonic SC markers and were capable of differentiating into cells of the three embryonic layers. [38]

Bone Marrow-derived Stem Cells (BMSC)

BMSCs are multipotent and can differentiate into cells with ectodermal, mesodermal and endodermal origin.[39][40]

Ma et al[41] investigated whether BMSCs can be used to treat corneal disorders. Their data showed that transplantation of human BMSCs on human amniotic membrane successfully reconstructed damaged rat corneal surface. Interestingly, the therapeutic effect of the transplantation was associated with the inhibition of inflammation and angiogenesis after transplantation of MSCs rather than the epithelial differentiation from BMSCs.

Ye et al[42] showed systemically transplanted BMSCs can engraft to injured cornea to promote wound healing, by differentiation, proliferation, and synergizing with haemotopoietic stem cells in a rabbit model of alkaline burn.

Same group showed bone marrow-derived progenitor cells can be stimulated by inflammatory mediators and play a role in corneal wound healing following alkali injury in rabbits. Corneal alkali injury induces a rapid bone marrow reaction to release not only inflammatory cells but also progenitor cells into circulation. Migrated bone marrow-derived progenitor cells can home to local sites to promote wound healing.[43] The effect of corneal injury on mobilization of endogenous MSCs and homing to the injured cornea was also shown by Lan et al.[44]

Adipose-derived Stem Cells (ASC)

The most important features of adipose tissue as a stem cell source are the relative dispensability of this tissue and the ease with which processed lipoaspi- rate derived (PLA) cells with MSC differentiation potential can be obtained in large quantities with minimal risk. Arnalich-Montiel et al[45] were the first group that investigated the ability of human PLA cells to repair/regenerate the corneal stroma of rabbits. Human PLA cells differentiate into functional keratocytes when injected into an ablated corneal stroma after 8 and 12 weeks, as assessed by the expression of the cornea-specific proteoglycan, keratocan, and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). Dr. Funderburgh’s laboratory showed ASCs could differentiate to keratocytes in vitro.[46] Moshirfar's lab took another approach and encapsulated human-ASCs within a hyaluronic acid (HA)–derived synthetic extracellular matrix (sECM) that provide support and guidance for stem cell growth and development and showed that h-ASCs can survive in vivo for 10 weeks and differentiated into functional keratocytes, as they expressed cornea-specific proteins, keratocan, and ALDH3A1.[47]

Future Research Prospects

The desire to restore vision is the motivation of development of successful tissue engineering that needs more knowledge about potential cell sources, scaffold material, trophic factors and fabrication technologies. A number of challenges still need to be addressed before stem cell transplantation can be successfully translated to the clinical setting.

One major challenge for corneal replacement therapy has been engineering a biocompatible tissue equivalent. Unfortunately, most investigational protocols in corneal bioengineering and corneal SC therapy rely on the use of animal products and/or allogeneic human cells and tissue that can result in the development of a range of ocular complications, such as graft-versus-host disease, cataract, dry eye, glaucoma as well as ocular surface disease including squamous cell carcinomas of the conjunctiva.[48]

Despite these practical problems, there is a vast optimism that in the near future the great promise of stem cell–based therapies to treat corneal blindness and restore sight could become a reality.

References

- ↑ Hay, E.D. Development of the vertebrate cornea. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1980; 63, 263 – 322.

- ↑ Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Kruse FE. Identification and characterization of limbal stem cells. Exp Eye Res 2005;81:247–264.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Funderburgh ML, Du Y, Mann MM, et al. PAX6 expression identifies progenitor cells for corneal keratocytes. FASEB J 2005;19:1371–1373.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Amano S, Yamagami S, Mimura T, et al. Corneal stromal and endothelial cell precursors. Cornea 2006;25:S73–S77.

- ↑ Yin J, Jurkunas U. Limbal Stem Cell Transplantation and Complications. Semin Ophthalmol. 2018;33(1):134-141.

- ↑ Ordonez P, Di Girolamo N. Limbal epithelial stem cells: role of the nichemicroenvironment. Stem Cells. 2012;30:100-7

- ↑ Goldberg MF, Bron AJ. Limbal palisades of Vogt. Trans Am Ophthmol Soc 1982;80:155–171.

- ↑ Majo F, Rochat A, Nicolas M, Jaoude GA, Barrandon Y. Oligopotent stem cells are distributed throughout the mammalian ocular surface. Nature, 2008; 456:250-254

- ↑ Sun TT, Tseng SC, Lavker RM. Location of corneal epithelial stem cells. Nature. 2010 Feb 25;463(7284):E10-1

- ↑ Chang CY, Green CR, McGhee CN, Sherwin T. Acute wound healing in the humancentral corneal epithelium appears to be independent of limbal stem cellinfluence. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5279-86

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Pellegrini G, Traverso CE, Franzi AT, et al. Long-term restoration of damaged corneal surfaces with autologous cultivated corneal epithelium. Lancet 1997;349:990–3.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Schwab IR, Reyes M, Isseroff RR. Successful transplantation of bioengineered tissue replacements in patients with ocular surface disease. Cornea 2000;19:421–6.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rama P, Bonini S, Lambiase A, et al. Autologous fibrin-cultured limbal stem cells permanently restore the corneal surface of patients with total limbal stem cell deficiency. Transplantation 2001;72:1478 – 85. 502.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Tsai RJ, Li LM, Chen JK. Reconstruction of damaged corneas by transplantation of autologous limbal epithelial cells. N Engl J Med 2000;343:86 –93.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Shimazaki J, Aiba M, Goto E, et al. Transplantation of human limbal epithelium cultivated on amniotic membrane for the treatment of severe ocular surface disorders. Ophthalmology 2002;109:1285–90.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Sotozono C, et al. Successful primary culture and autologous transplantation of corneal limbal epithelial cells from minimal biopsy for unilateral severe ocular surface disease. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2004;82:468–71.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Sotozono C, et al. Transplantation of autologous serum-derived cultivated corneal epithelial equiv- alents for the treatment of severe ocular surface disease. Ophthalmology 2006;113:1765–72.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Sangwan VS, Matalia HP, Vemuganti GK, et al. Clinical outcome of autologous cultivated limbal epithelium transplan- tation. Indian J Ophthalmol 2006;54:29–34.

- ↑ Varghese VM, Prasad T, Kumary TV. Optimization of culture conditions for an efficient xeno-feeder free limbal cell culture system towards ocular surfaceregeneration. Microsc Res Tech. 2010;73:1045-52

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Shortt AJ, Secker GA, Rajan MS, Meligonis G, Dart JK, Tuft SJ, Daniels JT. Ex vivo expansion and transplantation of limbal epithelial stem cells. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1989-97.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Kolli S, Ahmad S, Lako M, Figueiredo F. Successful clinical implementation of corneal epithelial stem cell therapy for treatment of unilateral limbal stem celldeficiency. Stem Cells. 2010 Mar 31;28(3):597-610.

- ↑ Yoshida S, Shimmura S, Shimazaki J, et al. Serum-free spheroid culture of mouse corneal keratocytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005; 46:1653–1658

- ↑ Du Y, Carlson EC, Funderburgh ML, Birk DE, Pearlman E, Guo N, Kao WW, Funderburgh JL. Stem cell therapy restores transparency to defective murine corneas. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1635-42

- ↑ Yokoo S, Yamagami S, Yanagi Y et al. Human corneal endothelial cell precursors isolated by sphere-forming assay. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46:1626–31.

- ↑ Yamagami S, Yokoo S, Mimura T, Takato T, Araie M, Amano S. Distribution of precursors in human corneal stromal cells and endothelial cells. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:433-9.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Burillon C, Huot L, Justin V, Nataf S, Chapuis F, Decullier E, Damour O. Cultured autologous oral mucosal epithelial cell sheet (CAOMECS) transplantation for the treatment of corneal limbal epithelial stem cell deficiency. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:1325-31.

- ↑ Pellegrini G,Golisano O,Paterna P, et al. Location and clonal analysis of stem cells and their differentiated progeny in the human ocular surface. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:769–782.

- ↑ Qi H, Zheng X, Yuan X, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. Potential localization of putative stem/progenitor cells in human bulbar conjunctival epithelium. J CellPhysiol. 2010;225:180-5.

- ↑ Sangwan VS, Vemuganti GK, Singh S, Balasubramanian D. Successful reconstruction of damaged ocular outer surface in humans using limbal and conjunctival stem cell cultures methods. Biosci Rep. 2003;23:169–174.

- ↑ Kerkis I, Kerkis A, Dozortsev D, et al. Isolation and characterization of a population of immature dental pulp stem cells expressing OCT-4 and other embryonic stem cell markers. Cells Tissues Organs 2006;184:105–16.

- ↑ Monteiro BG, Serafim RC, Melo GB, et al. Human immature dental pulp stem cells share key characteristic features with limbal stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2009;42:587-94.

- ↑ Jahoda CA, Whitehouse J, Reynolds AJ, et al. Hair follicle dermal cells differentiate into adipogenic and osteogenic lineages. Exp Dermatol 2003;12:849–859.

- ↑ Blazejewska EA, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Zenkel M, et al. Corneal limbal microenvironmnt can induce transdifferentiation of hair follicle stem cells into corneal epithelial-like cells. Stem Cells 2009;27:642–652.

- ↑ Meyer-Blazejewska EA, Call MK, Yamanaka O, et al. From hair to cornea: toward the therapeutic use of hair follicle-derived stem cells in the treatment of limbal stem cell deficiency. Stem Cells. 2011;29:57-66

- ↑ Nakamura T, Endo K, Kinoshita S. Identification of human oral keratinocyte stem/progenitor cells by neurotrophin receptor p75 and the role of neurotrophin/p75 signaling. Stem Cells 2007;25:628–38.

- ↑ Inatomi T, Nakamura T, Koizumi N, et al. Midterm results on ocular surface reconstruction using cultivated autologous oral mucosal epithelial transplantation. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;141:267 – 75.

- ↑ Yamato M, Utsumi M, Kushida A, Konno C, Kikuchi A, Okano T. Thermo-responsive culture dishes allow the intact harvest of multilayered keratinocyte sheets without dispase by reducing temper- ature. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:473–480.

- ↑ Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999;284:143–7.

- ↑ Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, et al. Multi-organ, multi- lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369 -377.

- ↑ Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002; 418:41– 49.

- ↑ Ma Y, Xu Y, Xiao Z, et al. Reconstruction of chemically burned rat corneal surface by bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:315-21.

- ↑ Ye J, Yao K, Kim JC. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in a rabbit corneal alkali burn model: engraftment and involvement in wound healing. Eye (Lond). 2006;20:482-90.

- ↑ Ye J, Lee SY, Kook KH, Yao K. Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells promote corneal wound healing following alkali injury. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:217-22.

- ↑ Lan Y, Kodati S, Lee HS, Omoto M, Jin Y, and Chauhan SK. Kinetics and Function of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Corneal Injury. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:3638–3644

- ↑ Arnalich-Montiel F, Pastor S, Blazquez-Martinez A, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells are a source for cell therapy of the corneal stroma. Stem Cells. 2008;26:570-9.

- ↑ Du Y, Roh DS, Funderburgh ML, Mann MM, Marra KG, Rubin JP, et al.. Adipose-derived stem cells differentiate to keratocytes in vitro. Mol Vis. 2010 ;16:2680-9

- ↑ Espandar L, Bunnell B, Wang GY, Gregory P, McBride C, Moshirfar M.Adipose-derived stem cells on hyaluronic acid-derived scaffold: a new horizon in bioengineered cornea. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:202-8.

- ↑ Di Girolamo N. Stem cells of the human cornea. Br Med Bull. 2011;100:191-207.