Advancing Wavelike Epitheliopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Advancing Wavelike Epitheliopathy

Disease & Pathology

Advancing Wavelike Epitheliopathy (AWE) is an uncommon disease characterized by well-demarcated, thickened, coarse plaques forming on the cornea. These have a wavelike or frond-like appearance on slit lamp exam and typically expands from the superior limbus toward the center of the cornea. Pathological samples of debrided epithelium show no sign of dysplasia or cellular irregularity, and the conjunctiva is spared.[1][2][3]

Etiology

The cause of AWE is currently poorly understood. Most theories postulate that AWE is a response to irritation to the corneal epithelial stem cells. Previous ocular surgeries, topical medications, contact lenses, chemical exposure, or inflammatory disorders have been identified as possible stimuli.[1][2][4][5]

Risk Factors

Medications that have been implicated in causing AWE include 5-fluorouracil, mitomycin C and interferon, topical antiglaucoma medications, contact lens solution and contact lens wear, and acyclovir. Illnesses that have been associated with AWE include atopic dermatitis, acne rosacea, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Surgery, toxic chemical exposure, infection, and ocular trauma are also risk factors for the disease.[1][2][3][4][6][7]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of AWE is not well understood and may be multifactorial. It may be a form of partial limbal stem cell dysfunction or deficiency. D'Aversa et al., in the first report of this disease, suggest that abnormal limbal stem cells proliferate and migrate throughout the cornea causing the development of the characteristic wavelike plaque.[1] Similarities between AWE and other limbal stem cell deficiencies further support this theory. These similarities include the following:

• Presenting symptoms of foreign body sensation, ocular irritation, and blurry vision[8]

• Pathology spreading from the involved limbus, with the superior limbus being the most common[9][10][11]

• Association with topical anti-glaucoma medications, trauma, contact lens utilization, and ocular surgery[8][9][10][11][12][13]

There is also some thought that the corneal nerves are affected with this condition. Confocal imaging has demonstrated a reduction in the sub-basal plexus density with the disease, and regenerated nerve bundles once treated. [5]

Primary Prevention

Because of the association with stem cell dysfunction, susceptible patients should avoid stimuli known to damage limbal stem cells, including toxins, trauma, and surgery. In patients diagnosed with advancing wavelike epitheliopathy, triggers such as the previously described risk factors should be avoided. Contact lenses, when worn, should be well maintained and extended wear should be avoided. Hydrogen peroxide solutions may minimize irritation.[8]

Diagnosis

AWE is diagnosed clinically with confocal microscopy and slit lamp exam. Additionally, tissue obtained during treatment should be sent for cytological analysis to confirm the diagnosis of AWE.[1]

History

This disease presents after the fourth decade of life and can present in one or both eyes. Men and women are affected equally. Any of the risk factors described above, including certain medications, trauma, ocular surgery, and inflammatory illnesses, and ocular surface squamous neoplasia may be associated with increased risk for development of AWE. [1][2][3][14]

Physical Examination

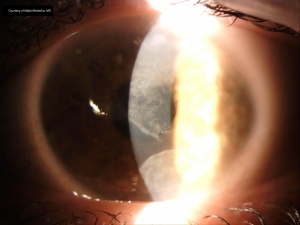

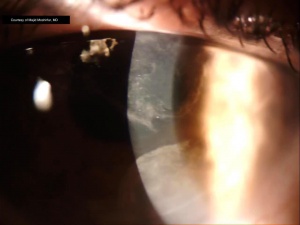

Wavelike plaques with well-defined borders are present, arising from the superior limbus and spreading toward the central cornea (figure 1). A granular texture with sclerotic scatter is visible on the corneal surface, and a subepithelial haze is sometimes appreciable (figure 2). No infiltrates or discrete inclusions are found. Fluorescein reveals a punctate staining pattern, also with distinct margins as visible with the slit lamp.[1][2][3] Atypical, elongated cells may be seen on confocal microscopy. These have a large nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, loss of visible cellular borders, and hyperreflective nuclei.[1][2][15]

Symptoms

Patients present with chronic or progressive blurry vision, occasionally with periods of remission, over the course of months to years. Ocular irritation, redness, and foreign body sensation are the most common presenting symptoms. Rarely, patients may be asymptomatic with small lesions that do not obstruct the visual axis. In these patients, simply removing causative agents may be sufficient for complete resolution.[1][2]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for AWE is extensive. Neoplastic pathologies, including corneal intraepithelial neoplasia, squamous cell carcinoma, and carcinoma in situ. Other disease processes that should be ruled out include superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis, corneal epithelial dysplasia, contact lens-induced keratopathy, hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis, whorled microcystic dystrophy, corneal epithelial keratinization, corneal pannus, prominent epithelial basement membrane dystrophy, and underlying inflammatory disorders.[1][2][3]

Management

Empiric silver nitrate solution applied topically after corneal epithelial debridement is the established treatment for AWE.[1] Other therapies have been used or proposed as described below.

Medical therapy

Cyclosporine, topical retinoids, interferon alpha-2b, and autologous topical serum drops are all theoretical treatments for AWE as these have been proven effective in other partial limbal stem cell deficiencies (LSCDs). These have not been formally reported in AWE, [16]but may be useful given the similarities between AWE and other LSCDs. Further clinical trials are necessary to prove this theory.[8][9][10][17][18]. Recently, a case report demonstrated improvement after the use of 5-FU and preservative free tears. [7]

Topical steroids and artificial tears have been used, and rarely provided improvement of AWE symptoms. The use of antibiotics, hypertonic saline, and bandage contact lenses also demonstrate no improvement in symptoms.[1][2]

Medical follow up

If medical therapy alone is attempted for treatment of AWE, the patient should be followed closely to observe and prevent progression of the disease.

Surgery

Identification and elimination of abnormal epithelium are important. As a temporizing measure, corneal epithelial debridement may be performed. Topical steroids and artificial tears may be used initially. Removal of diseased tissue results in temporary improvement of symptoms, but epitheliopathy often recurs within months. Standard therapy for AWE is comprised of corneal epithelial debridement with the empiric application of topical 1% silver nitrate solution. This is applied to the superior limbus, as described below. It is suggested that the silver nitrate chemically alters the abnormal limbal stem cells responsible for the disease, allowing them to regain normal functioning. Another theory suggests that silver nitrate or liquid nitrogen causes apoptosis of the abnormal cells, allowing normal stem cells to repopulate the corneal surface with healthy epithelium.[1][2][3][9]

Treatment with silver nitrate proceeds as follows[1]:

- Apply topical anesthetic such as topical proparacaine to the affected eye.

- Saturate a cotton-tipped applicator with the silver nitrate solution described above. (Note: The silver nitrate solution must be obtained from a sterile compounding pharmacy.)

- Roll the applicator across the affected area of the limbus and cornea while holding the eye open

- Irrigate copiously with normal saline.

- Apply a bandage contact lens for 3-4 days until re-epithelialization is complete.

- Treat with a topical antibiotic for one week.

Symptoms typically resolve within two weeks of silver nitrate treatment. The irregular tissue is replaced with normal-appearing epithelium, and most patients see a complete return of baseline vision. Occasionally patients may experience some minor residual vision loss.[1][2][3]

Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy has also been used with similar efficacy. [3]

Surgical follow up

The treated eye should be followed closely for signs of infection after treatment, with follow-up appointment within two weeks of treatment. Bandage contact lens may be removed after 3-4 days.

Complications

While a single treatment with silver nitrate is usually sufficient. Occasionally symptoms may recur, requiring additional silver nitrate treatments.[1]

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with AWE is excellent after treatment. Most patients experience complete resolution after a single application of silver nitrate. Some patients do exhibit small residual epithelial plaques; however, these are often small and usually do not occur with the visual axis. In cases where vision remains affected, repeat treatments result in continued improvement.[1]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 D’Aversa G, Luchs JL, Fox MJ, Rosenbaum PS, Udell IJ. Advancing wave-like epitheliopathy: Clinical features and treatment. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(6):962-969. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(97)30199-7

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Huang YH, Chu HS, Hu FR, Wang IJ, Hou YC, Chen WL. Recurrent advancing wavelike epitheliopathy from the opposite side of the initial presentation. Cornea. 2008;27(1):111-113.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Fraunfelder FW. Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy of advancing wavelike epitheliopathy. Cornea. 2006;25(2):196-198. doi:10.1097/01.ico.0000170691.67584.ec

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Gupta S, Selvan H, Markan A, Gupta V. Holi colors and chemical contact keratitis. 2018. doi:10.1038/eye.2017.223

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Babu K, Narasimha Murthy KYK, Ramachandra Murthy K. Wavelike epitheliopathy after phacoemulsification: Role of in vivo confocal microscopy. Cornea. 2007;26(6):747-748. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31804f59f3

- ↑ Caroline PJ, Andre M. Contact Lens Spectrum - Epitheliopathy in Contact Lens Wearers. Contact Lens Spectrum. https://www.clspectrum.com/issues/1999/february-1999/epitheliopathy-in-contact-lens-wearers. Published 1999. Accessed December 27, 2019.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Moratal Peiro B, Calvo Garcia R, Soler Sanchis I, Mata Moret L, Cervera Taulet E. Advancing wavelike epitheliopathy after conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Atipical case report. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed). 2022 Jun;97(6):337-339. doi: 10.1016/j.oftale.2021.04.005. Epub 2022 Feb 28. PMID: 35676026.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Rossen J, Amram A, Milani B, et al. Contact Lens-induced Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Ocul Surf. 2016;14(4):419-434. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2016.06.003

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Kim BY, Riaz KM, Bakhtiari P, et al. Medically Reversible Limbal Stem Cell Disease: Clinical Features and Management Strategies. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(10):2053-2058. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.025

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 Sangwan VS. Limbal stem cells in health and disease. Biosci Rep. 2001;21(4):385-405. doi:10.1023/A:1017935624867

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Jeng BH, Halfpenny CP, Meisler DM, Stock EL. Management of focal limbal stem cell deficiency associated with soft contact lens wear. Cornea. 2011;30(1):18-23. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181e2d0f5

- ↑ Dua HS, Saini JS, Azuara-Blanco A, Gupta P. Limbal stem cell deficiency: Concept, aetiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2000;48(2):83-92.

- ↑ Sridhar MS, Vemuganti GK, Bansal AK, Rao GN. Impression cytology-proven corneal stem cell deficiency in patients after surgeries involving the limbus. Cornea. 2001;20(2):145-148. doi:10.1097/00003226-200103000-00005

- ↑ Moratal Peiro B, Calvo Garcia R, Soler Sanchis I, Mata Moret L, Cervera Taulet E. Advancing wavelike epitheliopathy after conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Atipical case report. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed). 2022 Jun;97(6):337-339. doi: 10.1016/j.oftale.2021.04.005. Epub 2022 Feb 28. PMID: 35676026.

- ↑ Chiou AG-Y, Kaufman SC, Beuerman RW, Ohta T, Kaufman HE. A Confocal Microscopic Study of Advancing Wavelike Epitheliopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(1):123-124.

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554409/#article-88889.s10

- ↑ Tseng SCG, Maumenee AE, Stark WJ, et al. Topical Retinoid Treatment for Various Dry-eye Disorders. Ophthalmology. 1985;92(6):717-727. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(85)33968-4

- ↑ Tan JCK, Tat LT, Coroneo MT. Treatment of partial limbal stem cell deficiency with topical interferon α-2b and retinoic acid. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(7):944-948. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307411