Cataract: Difference between revisions

m (→Diagnostic Testing: Formatting.) |

m (→Diagnostic Testing: Formatting.) |

||

| Line 220: | Line 220: | ||

# Would removing the cataract likely lead to improved vision and improved level of functioning, and is the potential improvement enough to warrant the risks of surgery? | # Would removing the cataract likely lead to improved vision and improved level of functioning, and is the potential improvement enough to warrant the risks of surgery? | ||

# Would the patient tolerate the operation and be able to follow postoperative instructions and follow-up care? | # Would the patient tolerate the operation and be able to follow postoperative instructions and follow-up care? | ||

<br> | |||

If the answers to these questions lead the patient and physician to agree that surgical intervention is warranted, preoperative planning must be done. | If the answers to these questions lead the patient and physician to agree that surgical intervention is warranted, preoperative planning must be done. | ||

Revision as of 15:58, March 28, 2025

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

A cataract is a clouding of the natural intraocular crystalline lens that focuses the light entering the eye onto the retina. This cloudiness can cause a decrease in vision and may eventually lead to blindness if left untreated. Cataracts often develop slowly and painlessly, so vision and lifestyle can be affected without a person realizing it. Worldwide, cataracts are the number one cause of preventable blindness. There is no medical treatment to prevent the development or progression of cataracts. Modern cataract surgery, which is the removal of the cloudy lens and implantation of a clear intraocular lens (IOL), is the only definitive treatment. Approximately 3 million Americans choose to have cataract surgery each year, and it has an overall success rate of 97% or higher when performed in appropriate settings.

Cataracts often develop slowly with a gradual decline in vision that cannot be corrected with glasses. Common complaints include blurry vision, difficulty reading in dim light, poor vision at night, glare and halos around lights, and occasionally double vision. Other signs of cataracts include frequent changes in the prescription of glasses and a new ability to read without reading glasses in patients over 55.

There are several types of cataracts including age related, traumatic, and metabolic. Age-related cataract is the most common type, and the pathogenesis is multifactorial and not fully understood. A traumatic cataract can occur following both blunt and penetrating eye injuries, as well as after electrocution, chemical burns, and exposure to radiation. Metabolic cataracts occur in patients with uncontrolled diabetes, galactosemia, Wilson disease, and myotonic dystrophy.

Disease

While the majority of cataracts in the population are age-related, or senile, cataracts, there are many types and causes of cataract. This article will discuss the 3 most common types (nuclear, cortical, and posterior subcapsular), as well as other less common types including anterior subcapsular, posterior polar, traumatic, congenital, and polychromatic.

In age-related cataract, the pathogenesis of cataract development is multifactorial and includes the following:[1]

- Compaction and stiffening of the central lens material (nuclear sclerosis) as new layers of cortical (outer lens) fibers continue to proliferate over time

- Abnormal changes in lens proteins (crystallins) resulting in their chemical and structural alteration, leading to loss of transparency

- Pigmentation of lens proteins (yellow-->brown)

- Changes in the ionic components of the lens

Symptoms

A cataract is defined as any opacification of the eye's crystalline lens, and any of these changes that then lead to a degradation in the optical quality of the lens can cause visual symptoms. Because there is a wide variety of cataract types, there is a large spectrum of visual symptoms associated with cataractous changes.[2]

These symptoms may include the following:

- Blurred vision at distance or near (different types may affect distance greater than near or vice versa)

- Glare (halos or streaks around lights, difficulty seeing in the presence of bright lights)

- Difficulty seeing in low-light situations (including poor night vision)

- Loss of contrast sensitivity

- Loss of ability to discern colors

- Increasing near-sightedness or change in refractive status (including "second-sight" phenomenon)

Risk Factors

Risk factors for cataract development include the following:

- Diabetes or elevated blood sugar

- Steroid use (oral, IV, or inhaled)

- UV exposure

- Smoking

- Ocular diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa or uveitis

- Ocular trauma

- Prior ocular surgery

- Genetic predisposition

- Cataracts associated with dermatologic diseases

- Radiation or chemotherapy treatment

Common Types of Cataracts

Age-related cataract is by far the most common type, and it is further divided into 3 types based on the anatomy of the human lens: nuclear sclerotic, cortical, and posterior subcapsular. Patients commonly develop opacity in more than one area of their lens, which can cause overlap in the classification of cataracts.

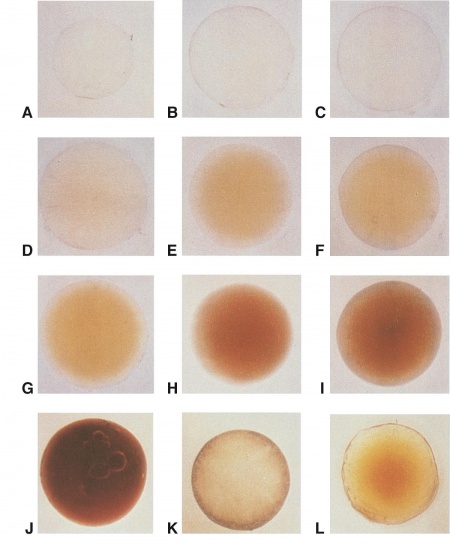

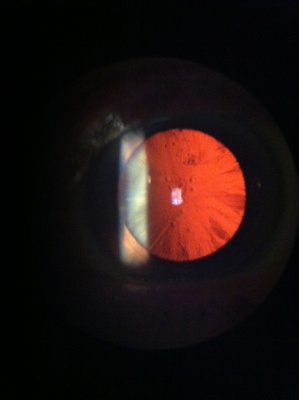

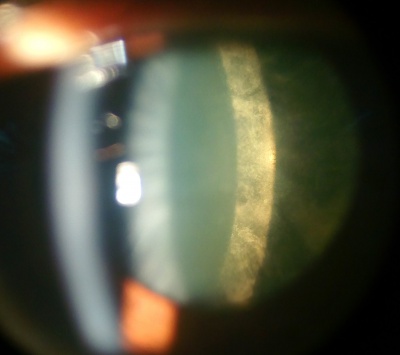

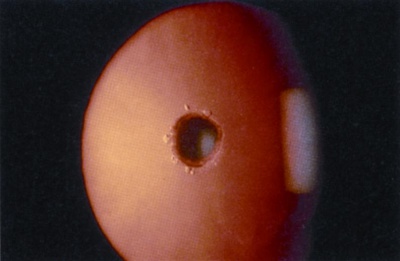

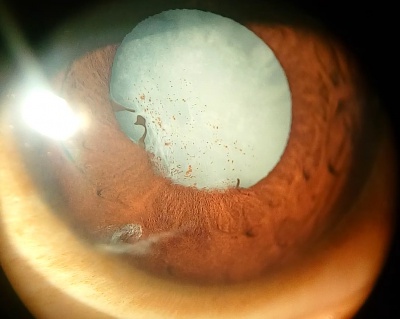

Nuclear Sclerotic Cataract

Etiology

Nuclear sclerosis is the yellowing and hardening of the central portion of the crystalline lens, and it occurs slowly over years. As the core of the lens hardens, it often causes the lens to increase the refractive power, leading to nearsightedness. This is why some patients who previously relied on reading glasses may no longer need them once a nuclear sclerotic cataract starts to form. This type of cataract can also cause colors to be less vibrant, although the change is so gradual that it is often not noticed.

Symptoms

- Blurring of distance more than near vision (typically, but others may notice worsening of reading more than distance)

- Increasing myopia ("second-sight" phenomenon of improved uncorrected distance vision in hyperopes and improved uncorrected near vision in emetropes)

- Poor vision in dark settings such as night driving

- Decreased contrast and decreased ability to discern colors

- Glare

- Monocular diplopia

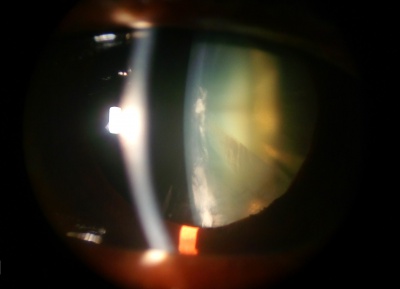

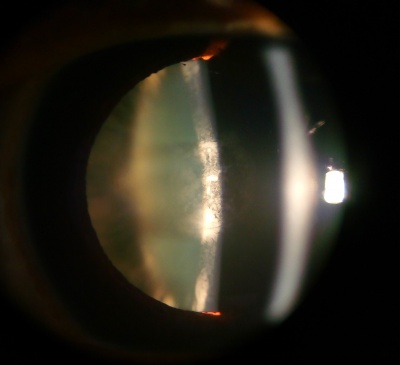

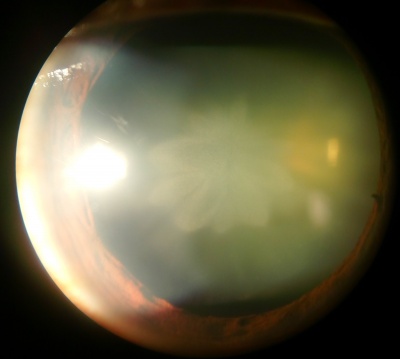

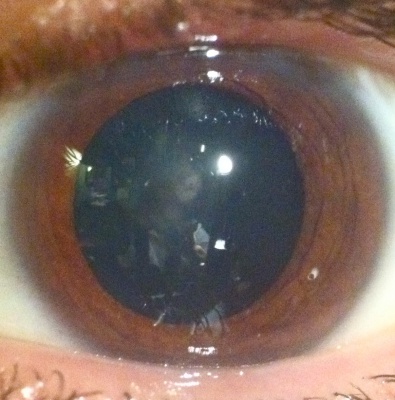

Cortical Cataract

Etiology

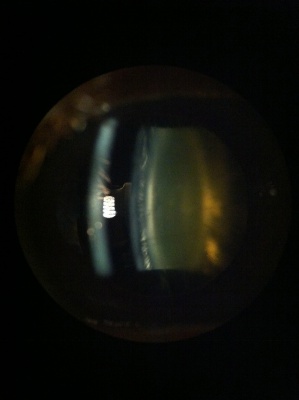

Cortical cataracts occur when the portion of lens fibers surrounding the nucleus become opacified. The impact on vision is related to how close the opacities are to the center of the visual axis, and their effect can vary greatly. Progression is variable, with some progressing over years and others in months. The most common symptom of cortical cataract is glare, especially from headlights while night driving.

Symptoms

- Glare often the predominate symptom

- Decreased distance and near vision

- Decreased contrast sensitivity

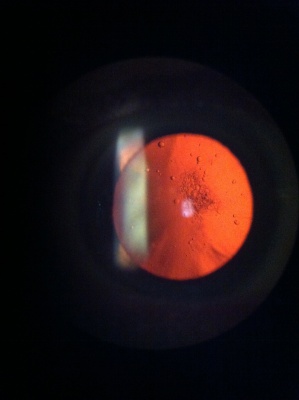

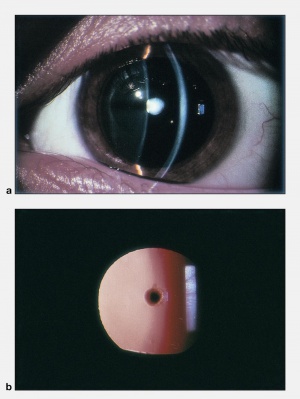

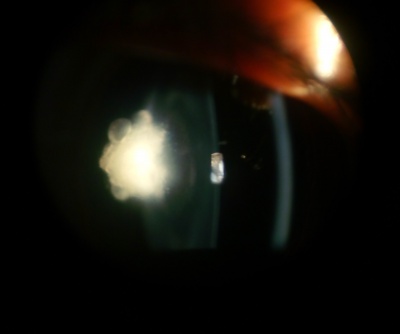

Posterior Subcapsular Cataract

Etiology

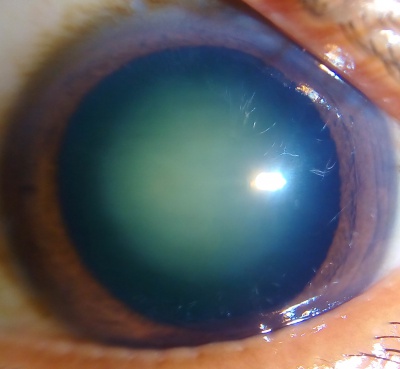

Posterior subcapsular cataracts (PSC) are opacities located in the most posterior cortical layer, directly under the lens capsule. This type of cataract tends to occur in younger patients compared to cortical or nuclear sclerotic cataracts. Progression is variable but tends to occur more rapidly than in nuclear sclerosis. Thus, PSC can reduce visual acuity earlier and quicker than its more common nuclear or cortical cataract counterparts. Equatorial and posterior cortical degeneration during PSC formation leads to posterior migration, inward displacement, and equatorial lens epithelial cell (LEC) malformations. During this aberrant migration of equatorial LECs to the posterior pole, many cells take on a characteristic ballooned or swollen bladder-like shape, first described by pathologist Carl Wedl. Accumulation of these dysplastic, nucleated, bladder cells, or Wedl cells, begins as a focal dot-like area in the posterior cortex, proceeding into granular opacities in the posterior pupillary zone of the lens, and in advanced cases, ultimately growing denser into a large, white, granular, vacuolar plaque. On slit-lamp examination, these opacified, granular plaques can appear similarly to posteriorly migrating Elschnig pearl formations postcataract. Histologically, Wedl cells are described by their scarce organelles, crystalline proteins, prominent cytoskeleton, and degenerating nuclei.

The exact mechanisms behind the pathologic migration or Wedl cell generation are not fully understood, although ionic uncoupling pathways, oxidative stress, and interleukin-induced LEC activation have all been suggested to play a role in pathogenesis. Risk factors for PSC and Wedl cell pathology include but are not limited to calcium imbalance, atopy, ionizing radiation, high or prolonged use of glucocorticoids, diabetes, myopia, ocular inflammation (uveitis), and vitrectomy. These Wedl cell aggregations, a signature hallmark of all PSC development, cause decreased visual acuity and contrast sensitivity. Symptoms include glare and difficulty seeing in bright light, and near vision is often more affected than distance.

Symptoms

- Glare

- Difficulty with near greater than distance vision (typically, but many patients may notice the opposite)

- Often rapidly diminishing vision

Other Types of Cataracts

Anterior Subcapsular Cataract

Etiology

Anterior subcapsular cataracts can develop idiopathically, may be secondary to trauma, or may be iatrogenic. Phakic intraocular lenses used to correct refractive error, such as the Visian implantable collamer lens (ICL), have been reported to cause anterior subcapsular cataracts due to ICL-lens touch from inadequate vaulting of the ICL.

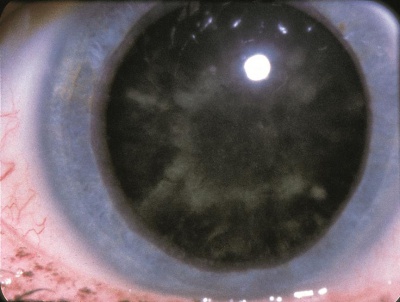

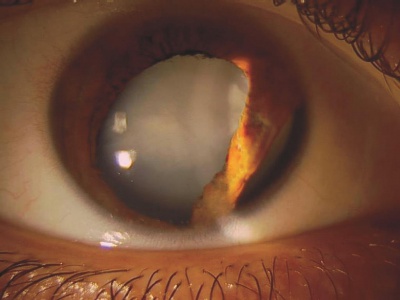

Diabetic Snowflake Cataract

Etiology

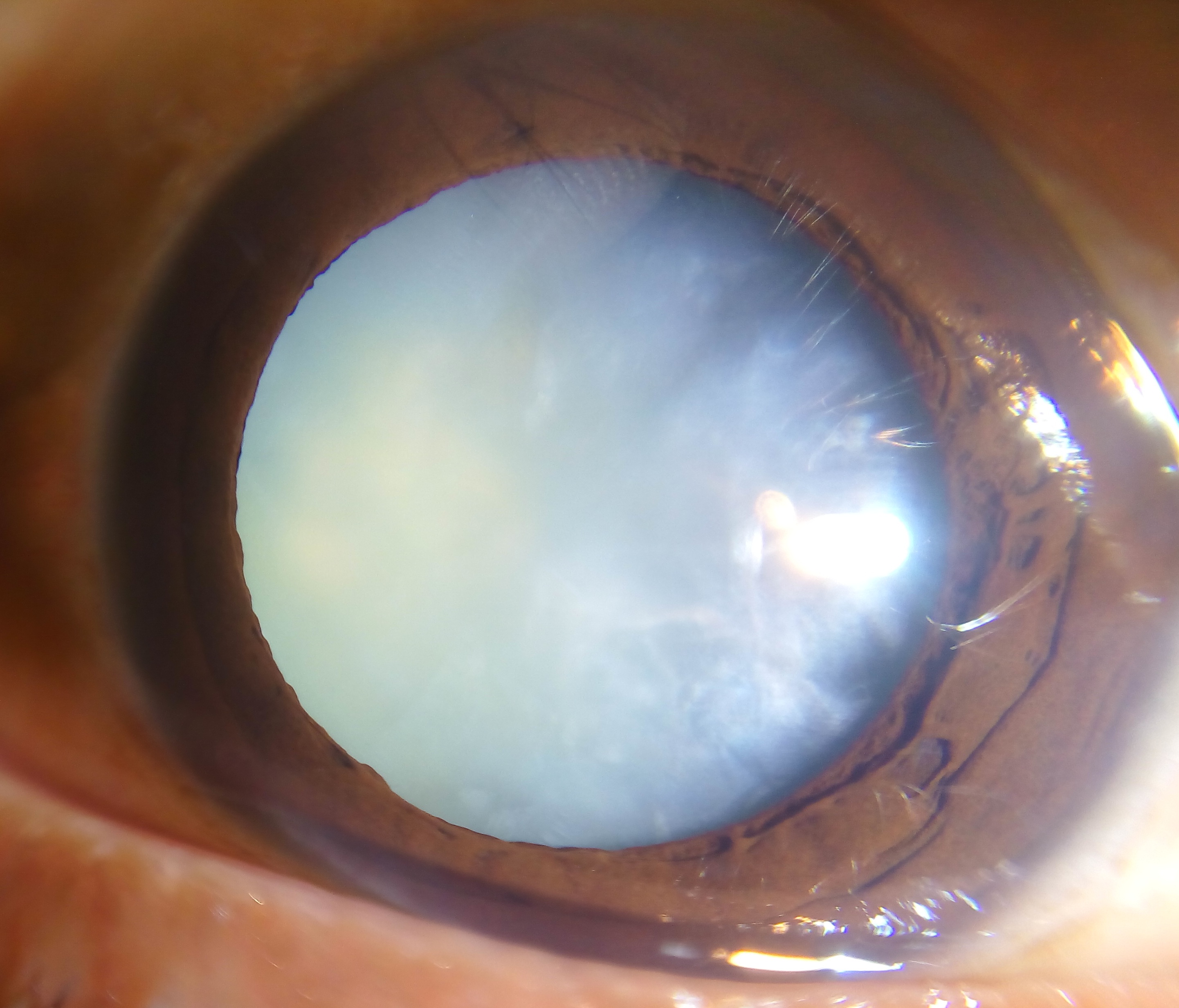

Diabetic snowflake cataracts appear as gray-white subcapsular opacities. Often, these cataracts progress rapidly, and the entire lens becomes intumescent and white. Cataracts often occur at younger ages in diabetic patients due to osmotic stress from intracellular accumulation of sorbitol in the lens secondary to elevated intraocular glucose. A rapid-onset form of cataract, which is quite uncommon, may be found in some diabetic patients with very elevated blood sugars, especially younger type 1 diabetics.

Posterior Polar Cataract

Etiology

Posterior polar cataracts are characterized by well-demarcated white opacities in the center of the posterior capsule. These opacities often project forward as cylinders penetrating into the posterior lens cortex. Posterior polar cataracts are typically congenital with autosomal dominant inheritance.

Symptoms

Most posterior polar cataracts are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic. However, over time, posterior subcapsular opacities may form around the posterior polar opacity. As the cataract progresses, vision may be severely affected.

Posterior polar cataracts pose a unique challenge for cataract surgery. The rate of posterior capsular rupture is significantly higher in these cases. The posterior capsule is weakened around the posterior polar opacity, and in some cases, there may even be a defect in the capsule.

Traumatic Cataract

Etiology

A traumatic cataract develops in the affected eye after an incident. A cataract can occur following both blunt and penetrating eye injuries, as well as after electrocution, chemical burns, and exposure to radiation.

Symptoms

Clouding of the lens at the site of injury may extend to the whole lens. Development can be rapid after the incident.

Congenital Cataract

Etiology

Congenital cataracts can occur as unilateral or bilateral isolated findings or may be associated with systemic disease. Most cases associated with systemic disease are bilateral. Approximately 1 in every 250 children in the United States is born with a congenital cataract (defined as some lens opacity present at birth), but many are subclinical.

In general:

- 1/3 are associated with systemic disease

- 1/3 are inherited traits

- 1/3 are of undetermined cause

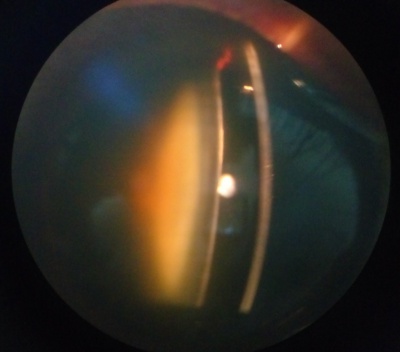

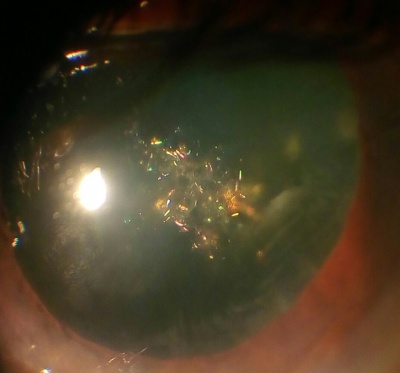

Polychromatic Cataract

Etiology

Also known as a "Christmas tree" cataract, polychromatic cataracts consist of highly reflective, iridescent corneal crystals of various colors. They may be seen as a rare variant of senile cataractous development, and they are also found with a higher prevalence in patients with myotonic dystrophy.

Diagnostic Testing

When patients are evaluated for cataracts, the primary objective is to determine the following:

- Is there is a visually significant lens opacity?

- Does the lens opacity account for the patient's level of vision?

- Would removing the cataract likely lead to improved vision and improved level of functioning, and is the potential improvement enough to warrant the risks of surgery?

- Would the patient tolerate the operation and be able to follow postoperative instructions and follow-up care?

If the answers to these questions lead the patient and physician to agree that surgical intervention is warranted, preoperative planning must be done.

Ophthalmic Examination

Visual function is determined by asking patients how they are limited in function by their vision and by measuring their visual acuity with and without spectacle correction. In patients complaining of glare, brightness acuity is tested by asking a patient to read the eye chart while shining a bright light at the patient from the side. There are also other instruments that can mimic glare. These simulate the oncoming headlights of night driving and can reveal functional impairment. A comprehensive dilated eye exam is performed on all patients when possible. Specific attention is paid to several factors affecting surgical planning, including the severity of the cataract; the size of the dilated pupil (smaller pupils increase the complication rate); the clarity, thickness, and health of the cornea; the stability of the lens; the depth of the anterior chamber; and the health of the optic nerve and retina.

Preoperative Measurements

To get the best possible visual outcomes, several preoperative measurements are necessary to determine the power of the IOL implant. A careful refraction of both eyes, especially if planning on operating on only 1 eye, is needed to avoid dissimilar refractive errors postoperatively, as this can be disturbing to patients. To determine the IOL power needed, measurements of the axial length of the eye, the corneal refractive power, and the anterior chamber depth are taken. Additional tests that can be helpful in select cases include corneal topography and endothelial cell counts.

Management

Nonsurgical Treatment

No medical treatment has been shown to be effective in the treatment or prevention of cataracts, although this is an active area of research. To slow the development of cataracts, it is generally recommended that patients eat a balanced diet, prevent excessive exposure to UV radiation by using good-quality UV-blocking sunglasses, avoid injuries by using protective eyewear, and if diabetic, closely control blood sugar levels.

Other approaches to temporarily improve visual function include careful refraction to get the best-corrected vision, pharmacological dilation, increased lighting, and the use of magnifiers for near work.

Surgical Treatment

Cataract surgery is one of the most common surgical procedures performed around the world and has a very high success rate. The most common type of cataract surgery in the United States utilizes ultrasound energy to break the cataract into particles small enough to aspirate through a handpiece. This technique is referred to as phacoemulsification. Other techniques include manual extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) in which the entire nucleus of the cataract is removed from the eye in 1 piece after extracting it from the capsular bag. While ECCE traditionally involved a large incision that required multiple sutures, a newer technique known by many names (such as manual small-incision cataract surgery or small-incision ECCE) allows for manual extraction without the need for any sutures.

The goal in modern cataract surgery is not only the removal of the cataract but also its replacement with an intraocular lens. The IOL is typically placed during the cataract surgery, and it may be placed in the capsular bag as a posterior chamber lens (PCIOL), in the ciliary sulcus as a sulcus lens, or in the anterior chamber anterior to the iris as an anterior chamber lens (ACIOL). There are multiple types of IOLs that may be used in modern cataract surgery, including monofocal, multifocal, accommodative, light-adjustable, and astigmatism-correcting lenses. The goal of all IOLs is to improve vision and limit dependency on spectacles or contact lenses.

Recently, the femtosecond laser, familiar to the refractive ophthalmologist for its role in LASIK, Intacs, and corneal transplantation, has been adapted to assist in cataract surgery. This procedure still relies on the cataract surgeon to remove lens material in a manner similar to phacoemulsification, but it replaces several manual steps of the procedure with a more automated laser mechanism.

Additional Resources

- AAO PPP Cataract and Anterior Segment Panel, Hoskins Center for Quality Eye Care. Cataract in the adult eye PPP 2021. American Academy of Ophthalmology. November 2021. https://www.aao.org/education/preferred-practice-pattern/cataract-in-adult-eye-ppp-2021-in-press

- Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 11. Lens and Cataract. American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2023-2024.

- Boyd K, McKinney JK, Turbert D. Cataracts. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. Accessed August 16, 2023. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/cataracts-list

- Plager D, Carter C. Focal Points. Pediatric Cataract. American Academy of Ophthalmology. February 2011.

References

- ↑ Evaluation and management of cataracts. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 11. Lens and Cataract. American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2023-2024:79-93.

- ↑ AAO PPP Cataract and Anterior Segment Panel, Hoskins Center for Quality Eye Care. Cataract in the adult eye PPP 2021. American Academy of Ophthalmology. November 2021. https://www.aao.org/education/preferred-practice-pattern/cataract-in-adult-eye-ppp-2021-in-press