All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Serpiginous choroidopathy (SC) is a rare, bilateral, chronic, progressive, recurrent inflammatory disease of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), choriocapillaris and choroid of unknown etiology.[1][2] [3]

Etiology

SC is a rare clinical entity causing less than 5% of posterior uveitis cases. It has a higher prevalence in men and affects young to middle-aged adults. No systemic disease associations have been identified. [4]

Pathophysiology

Although of unknown etiology, its origin is probably immunogenic since it seems to respond to treatment with corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants. Moreover, affected patients also show an increased frequency of HLA-B7 and retinal S-antigen associations. Other pathogenic mechanisms have been proposed and there may be an association with SC with infectious etiologies such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and herpes viruses but this remains to be proven. Alternatively, SC and tuberculosis-related SC may be different disease entities with overlapping features. [5]

Symptoms

Patients present with a painless unilateral vision loss, metamorphopsia or central scotoma.

Diagnosis

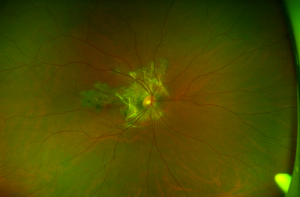

SC presents with gray-yellowish subretinal infiltrates that usually spread centrifugally from the peripapillary region in a serpiginous (snake-like) manner. Active lesions show a leading edge and resolve with subsequent RPE and choriocapillary atrophy. Consecutive recurrences cause further atrophy leaving hypo- and hyper-pigmented lesions that spread irregularly over the posterior fundus. Although bilateral, the disease is often asymmetric with multiple lesions in different stages of resolution in both eyes. Recurrences have variable intervals that range from months to years. Anterior chamber and vitritis are minimal. [4]

Others forms of SC include macular serpiginous choroidopathy and ampiginous chorioretinopathy (also known as relentless placoid chorioretinitis). The former begins as a macular lesion that spares the peripapillary region with a higher risk of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) and poor visual outcome. Ampiginous chorioretinopathy is characterized by multifocal plaque-like lesions scattered over the posterior pole that has overlapping features of both acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epiteliopathy (APMPPE) and SC. Ampiginous chorioretinopathy is characterized by multiple recurrences and progressive enlargement of serpiginous lesions over time without the spontaneous resolution typical of APMPPE.

Diagnostic procedures

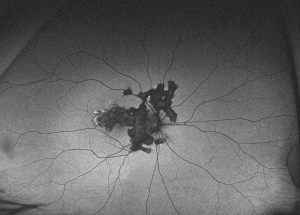

Ancillary testing in SC include fluorescein angiography (FA), indocyanine green angiography (ICG) and fundus autofluorescence (FAF). In active lesions occurring at the margins of an atrophic lesion, FA typically shows early hypofluorescence with late leakage. As in other inflammatory choroidopathies, ICG is characterized by hypofluorescent areas from early to late frames.[4] FAF has become increasingly useful and a minimally invasive tool for monitoring disease progression in SC. [6] Active lesions show a hypoautofluorescent halo surrounding the edges of a hyperautofluorescent lesion. Semi-active or transitional lesions show a linear hypoautofluorescence surrounding all edges of the hyperautofluorescent lesion. Quiet or inactive lesions are dark and uniformly hypoautofluorescent.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes other etiologies for posterior uveitis that cause multifocal or placoid chorioretinitis like multifocal chorioretinitis, APMPPE, toxoplasmosis and tuberculosis (TB).

TB has recently been associated with the development of a choroidopathy that mimics SC commonly named serpiginous-like choroidopathy (SLC).[7] This disease probably represents a hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, which leads to the development of a chorioretinitis that is similar to SC. This poses a diagnostic challenge since these two disease entities have a very different therapeutic approach and antibacillary treatment associated with oral corticosteroids is mandatory for SLC in order to avoid future recurrences. Recent works claim that SLC can be distinguished from SC because the lesions are noncontiguous to the optic disc, are frequently multifocal with a more peripheral involvement, tend to spare the fovea even in eyes with macular involvement and commonly course with vitritis. SLC may not respond to sole treatment with steroids and/or other immunosuppressants making TB testing (with tuberculin skin testing or QuantiFERON-TB Gold) mandatory, especially in a patient from endemic regions.

Medical therapy

Treatment of SC aims to stop chorioretinal inflammation especially when the advancing lesions threaten the fovea. Systemic or periocular corticosteroids are frequently used but recurrence prevention usually requires long term anti-inflammatory treatment with a steroid-sparing agent, such as antimetabolites (methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine), cyclosporine A, or anti-TNF agents, such as adalimumab or infliximab, once tuberculosis has been ruled out.[8] Long term management can be challenging and up to 25% of the eyes have a final visual acuity less than 20/200.

Complications

The most common complication of SC is choroidal neovascularization affecting up to 35% of patients. Other reported complications are subretinal fibrosis, cystoid macular edema, branch vein occlusion, serous retinal detachment, optic disc neovascularization and anterior uveitis. [9][4]

Prognosis

SC is a challenging disease, likely autoimmune in origin and frequently managed with systemic corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants. Tuberculosis testing is critical in this setting since SLC has a different therapeutic approach and clinical course.

References

- ↑ Bacin F, Larmande J, Boulmier A, Juliiar G. Serpiginous choroiditis and placoid epitheliopathy. Bull Soc Opthalmol Fr. 1983; 83:1153-62

- ↑ Abu el-Asrar AM. Serpiginous (geographical) choroiditis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1995; 35:87-91

- ↑ Ciulla TA, Gragoudas ES. Serpiginous choroiditis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1996; 36:135-43.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Nazari Khanamiri H, Rao NA. Serpiginous choroiditis and infectious multifocal serpiginoid choroiditis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013 May-Jun;58(3):203-32.

- ↑ Gupta V, Gupta A, Arora S, Bambery P, Dogra MR, Agarwal A. Presumed tubercular serpiginouslike choroiditis: clinical presentations and management. Ophthalmology. 2003 Sep;110(9):1744-9.

- ↑ Cardillo Piccolino F, Grosso A, Savini E. Fundus autofluorescence in serpiginous choroiditis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247(2):179–85.

- ↑ Bansal R, Gupta A, Gupta V, Dogra M, Sharma A, Bambery P. Tubercular serpiginous-like choroiditis presenting as multifocal serpiginoid choroiditis. Ophthalmology. 2012; 119(11): 2334-42.

- ↑ Akpek EK, Jabs DA, Tessler HH, Joondeph BC, Foster CS. Sucessful treatment of serpiginous choroiditis with alkylating agents. Ophthalmology. 2002; 109(8): 1506-13.

- ↑ Steinmetz RL, Fitzke FW, Bird AC. Treatment of cystoids macular edema with acetazolamide in a patient with serpiginous choroidopathy. Retina. 1991; 11:412-5.